Here, in a feature we call How I Teach, we ask educators how they approach their jobs. You can see other pieces in the series here.

When Bryan Bassette looks at his students, he thinks: “I used to be you.”

Like his students, Bassette grew up in Oakland, California. His father moved the family to the city’s westside in the late 1970s to be part of the Black Panther movement. But when Bassette attended a predominantly white, affluent elementary school, he says he didn’t receive the kind of support his students do now.

“Someone who looks like them, who has a similar experience,” he said. “I don’t think I could do what I do in the classroom without those relationships.”

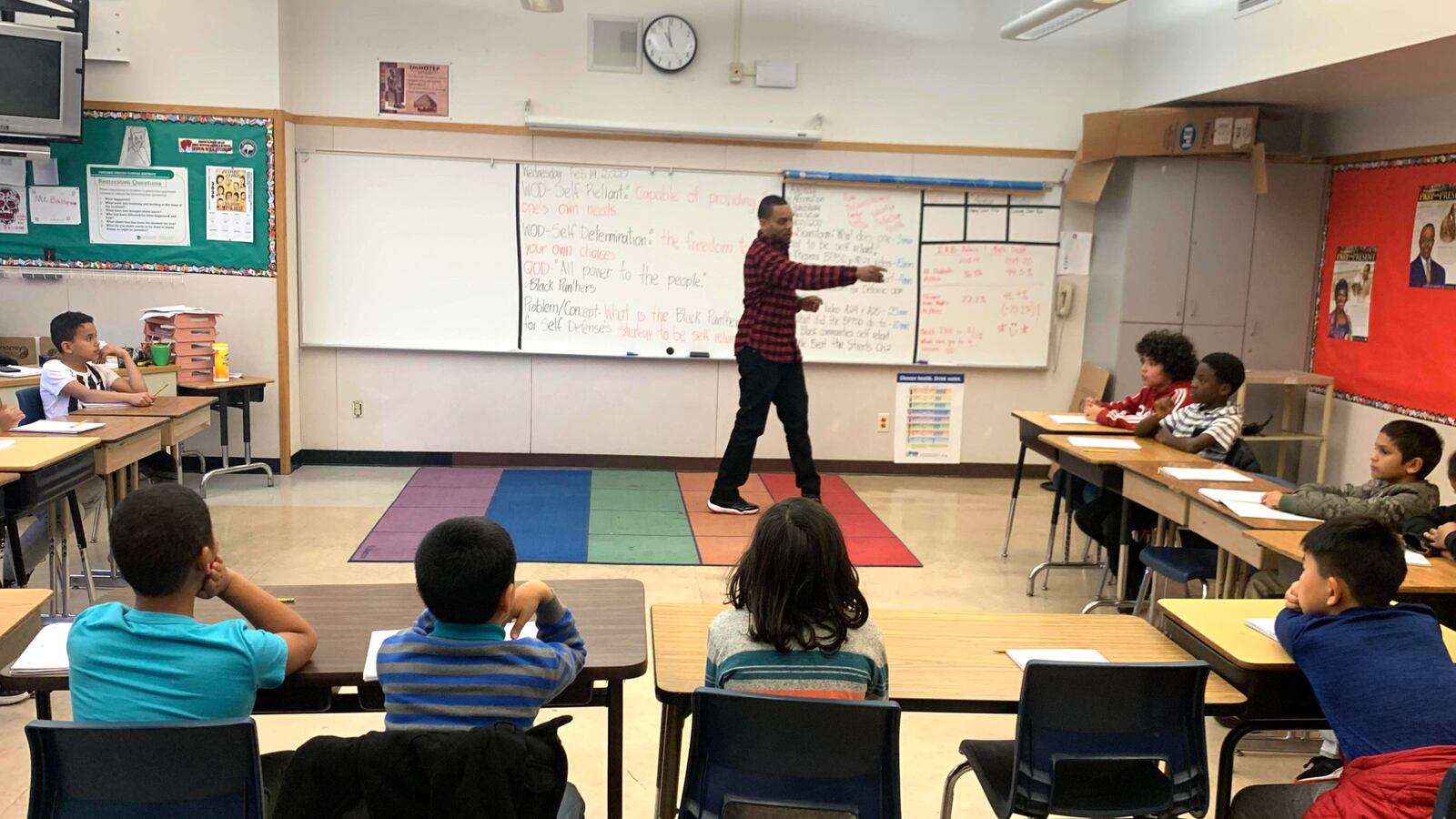

Bassette teaches in the Manhood Development Program in Oakland Unified School District. It’s a signature part of the district’s Office of African American Male Achievement, which launched in 2010. Since then, other districts, including Minneapolis, have started similar initiatives.

A crucial component of the program is an elective class aimed at black boys and taught by black male educators. It includes a mixture of African and African American history and culture, as well as mentoring. Now offered in some two dozen Oakland schools, it’s been found to reduce the high school dropout rate among black male students. Six years ago, Bassette was the first to pilot the class with younger students at Piedmont Avenue Elementary, where he still teaches.

He has 53 students, or “kings,” as they’re known in the program, on his roster, including some Latino, white and Asian boys. Bassette says he fell in love with teaching the class — “I liked the fact that I was learning with the kids” — and has been recognized for his work in the program. He’s now working toward his master’s in education so he can become a principal.

He’s known to many as “Brother Bryan,” a familial designation given to teachers in the program to signify that they’re all in the work together.

“We have this thing we call ‘collective genius,’” he said. “We can lean on one another to build our practice, to build our pedagogy, so we can become better teachers.”

We talked with Bassette about his parents’ deep roots in education, how he earns his students’ trust, and teaching complex lessons about racism to fourth- and fifth-graders.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Was there a specific moment you decided to become a teacher?

Both of my parents are teachers. My dad was a high school AP economics and government teacher, my mom was an elementary school teacher. I played baseball in college and so when I was in school, my mom said I should get my teaching credential. I told her: ‘Mom, I’m never teaching nothing.’ I was like a lot of boys and young men, I was chasing the dream of going pro in baseball. I ended up not getting drafted and I was just a student for the first time in my life. I ended up getting academically disqualified from college because I didn’t see a reason for me to be in school, so I stopped really applying myself.

I started coaching baseball at the high school level and I fell in love with it, and I really enjoyed the relationship with the kids and what I was doing. I went back to school and got my BA. It’s funny, as much as I fought my mom, I should have listened to her about 10 years ago.

How do you get to know your students?

A big part of it is sharing my experience and being transparent, and also trying to set my class up in a way that’s going to be fun and engaging for them. We go out and we play basketball, we play a lot of team-building games within the day. And as much as I can, I try to find individual time with them. My goal is to let them know: Yes, I’m your teacher, but on a very basic level, first, I love you and I want you to be successful.

Do you have a favorite lesson that you look forward to teaching?

The Black Panther one is my favorite lesson. We don’t start in Oakland in 1966 — that lesson actually begins with the Haitian Revolution in 1791, and then we chronicle all the way up to 1966 with the different armed resistance movements of the black community, so the students get some depth about this fight for equality and the fight against racism.

In school we don’t really learn about the full history of colonialism and what happened during slavery. And they don’t understand that this fight has been going on for centuries, and that African Americans and the African diaspora — we have a lot of wins in this fight. The Haitian Revolution chronicles the brothers and sisters in Haiti liberating themselves from slavery, from France, from Spain, and then starting their own country, and their own democracy.

By the end of it, what changes have you seen in your students when they are exposed to this lesson?

Just the pride, and a lot of ‘Wow, I didn’t know that happened.’ A lot of the stories about slavery are that we were dominated and subservient and complacent in it, and that’s just not the case. It’s kind of eye-opening to them. I really like the video that I use. It kind of takes them on an emotional roller coaster, where it talks about the history of Haiti and the colony that was there, what they were experiencing during slavery and how they got out of it. I’ve had students crying about what they see. But by the end of it, they give it a standing ovation.

What was your biggest misconception that you initially brought to teaching?

One of the biggest misconceptions is that I didn’t give them enough credit for their levels of intelligence and what they could comprehend. You’re talking about systemic racism and historically what has happened with race in this country. It’s really complex and it’s a lot of small details that they have to understand to see the big picture. The curriculum that I’m using was designed for middle and high school, so I have to take it and scaffold it and make it age-appropriate. I was not sure if elementary kids would be able to grasp a lot of these concepts — but they understand a whole lot more than I ever gave them credit for.

What’s something happening in the community that affects what goes on inside your class?

What isn’t affecting what’s going in my classroom? The trauma and some of the violence they see in the neighborhood. But the political climate and what is being said by politicians about immigration and the whole business of the impeachment. It’s funny to hear fourth- and fifth- graders talk about impeaching Trump. That comes up a lot in class, because they hear a lot of the rhetoric in the media and from their parents’ conversations. So they come to school with questions. And all those questions are really heartening and provide information and talking points to the topics that we have in class.

What’s the best advice you’ve received about teaching?

Kids don’t care what you know until they know that you care. Especially our kings from these rough neighborhoods, they’ve seen a lot in their lives and building trust is huge for them. My kids are not going to just listen and engage and respect me as a teacher, just because I have the title of teacher. I have to earn their trust.