Kaitlyn Casanas has watched as educators across the country begin teaching students remotely as schools close due to the new coronavirus.

When she looks at photos of lots of students learning online together, she thinks: “Oh my gosh, that just looks perfect.” But she knows for a lot of teachers, that just doesn’t reflect reality.

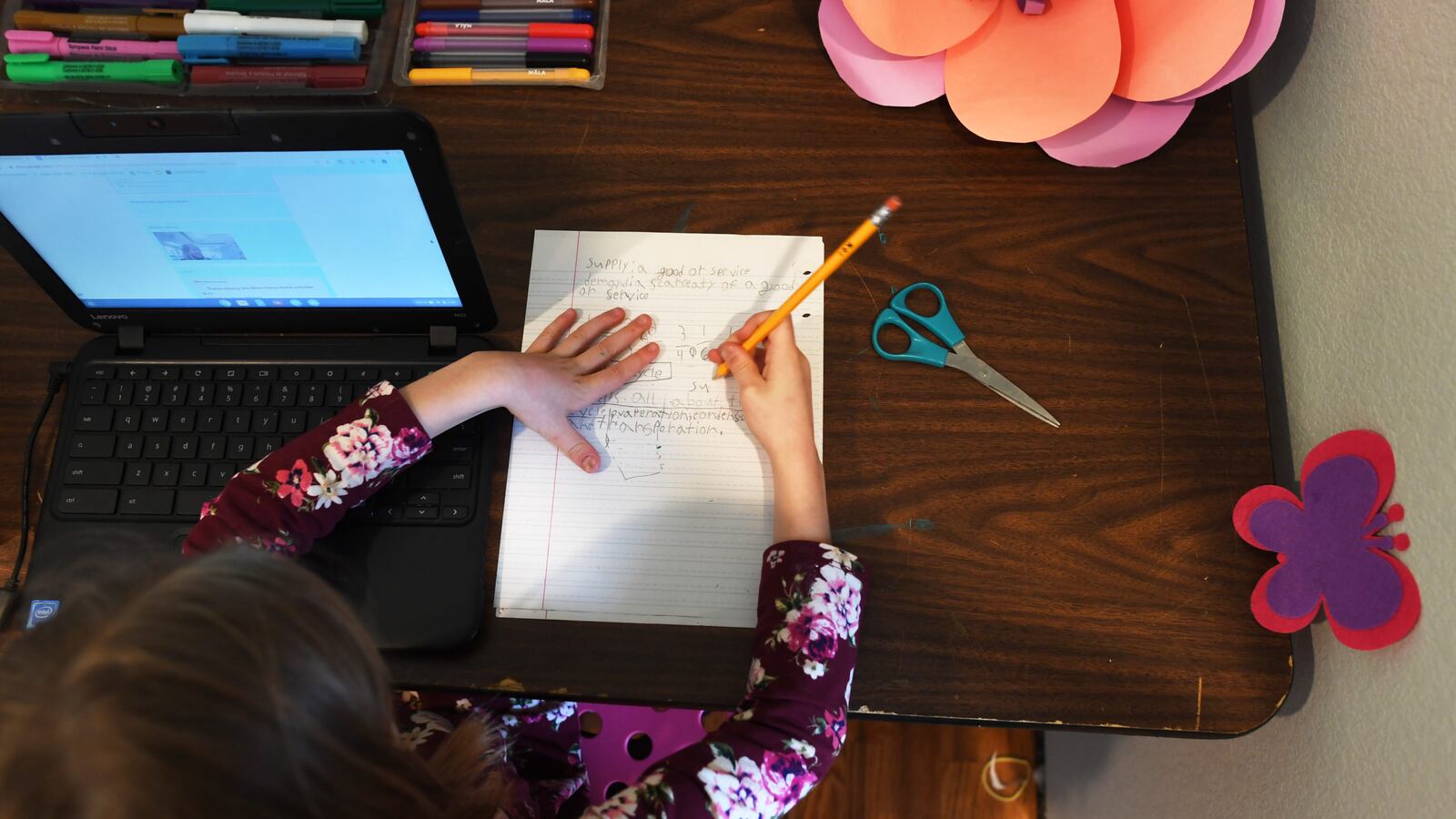

For Casanas, a teacher of students with intellectual disabilities at Southwest Miami Senior High, this is what it’s really like.

None of her students can log into a computer without help from an adult, and some of their parents have never used a laptop before — a “double whammy,” as Casanas put it. It was impossible to teach students how to use new devices in the two days she had to prepare before her school closed. Some of her students haven’t responded to her messages or logged onto their online programs yet.

They’re not alone: many students and parents have experienced problems with their online educational programs, the Miami Herald reported, even though Miami-Dade County public schools officials were proactive in planning to go remote.

“I’ve been a nervous wreck,” Casanas said. “In the back of your head, you’re like, ‘Am I doing enough?’ That’s my biggest worry, I don’t want to fail my students during this time. My brain is constantly [thinking]: How can I do this better?”

Teachers aren’t the only ones feeling this way. Parents of students with disabilities are also worried about helping their children log in and access the right services and support online, said Isabel Garcia, the long-time head of Parent to Parent of Miami, a nonprofit that advocates for parents of children with disabilities.

“The stress and the anxiety of the parents, it’s probably the highest that I have ever experienced, even during a hurricane,” Garcia said.

Miami-Dade, the country’s fourth-largest school district, is trying what few other of the biggest districts are right now: remote learning for all, including its students with disabilities. The district is better prepared than most, with lots of devices for students to take home and many teachers with experience using technology in the classroom.

Still, the first few days of this experiment have proved tough for teachers, and especially parents, of students with disabilities. And as other districts consider remote learning as it becomes clear that closures are likely to extend beyond a short break, Miami’s experience may tell us what challenges lie ahead.

“The key word is fluid,” said Jodi English, a veteran teacher who works with students with significant cognitive disabilities at Miami Southridge Senior High. “We’re all learning as we’re doing it.”

Nationwide, there’s been some confusion among districts about whether they can and should offer remote education while school buildings are closed. Most of the nation’s 10 largest school districts are planning to offer remote learning soon, but Miami-Dade was among the first to try it, rolling it out districtwide this week.

Much of the concern centers around whether that instruction will be accessible to students with disabilities. Some have criticized guidance issued by the U.S. Department of Education last week that said if districts closed their school buildings but continued to offer instruction, they had to ensure that students with disabilities had equal access and were receiving the services outlined in their special education plans “to the greatest extent possible.”

Some districts, like Philadelphia, then told schools they couldn’t offer remote education because they don’t have the ability to serve all students equally. The district later clarified its schools can offer, but not require, remote education.

Now that some states have signaled schools may be closed through the end of the school year, some education organizations are asking for more guidance about how schools can make accommodations for students with disabilities but not discourage schools from offering instruction.

The Miami teachers’ experience illustrates those tradeoffs. While teachers say remote learning may work for some students with disabilities — and it’s certainly better than no instruction at all — others say even their best virtual efforts will never measure up to what they could do with their students in person.

🔗One district’s experience

As schools forge ahead with remote learning, Miami-Dade’s experience shows there are lots of concrete ways to help teachers and parents — though it also helps to have gotten a head start.

Several special education teachers said district officials did a lot to try to help them this week. The district offered training sessions for special education teachers to learn new programs and video chat software. Officials distributed tens of thousands of devices to students, helped them connect to free WiFi hotspots provided by Comcast, and even set up a remote learning hotline. When Casanas called it yesterday to help a parent with laptop trouble, she was relieved to find there was no wait.

Teachers also got remote access to their students’ Individualized Education Programs — which outline what special education services they require — and were able to check a districtwide plan that includes some guidance on how to accommodate students with disabilities.

But teachers said they definitely had a leg up if they’d already used the computer programs the district recommended for students with disabilities.

English, for example, was glad her students had previously used one of the recommended math and reading programs, called iReady, so they could do activities on it without a parent’s help. She’d already helped them make easy passwords, and they’d practiced logging in “over and over and over again.”

“If they didn’t know how to do that already, that would have been an issue,” she said.

Duysevi Miyar, who teaches students with cognitive disabilities at Country Club Middle School, was familiar with using remote learning for students with disabilities because she studied it in her doctorate program, and she, too, had already used a lot of technology in her classroom.

She said her students had done a good job adapting this week — she had them send her photos when they’d finished their work — and they were staying in close contact through a Whatsapp group. But she knows not all teachers have the same experience.

“My co-teacher is dependent on me for doing a lot of this,” she said. “I know teachers that are not prepared and don’t have any communication with their students.”

But there are still major questions about how students with disabilities will fare if closures last for a long time.

Already, Garcia, of Parent to Parent of Miami, says her staff is advising families that they’ll be available to help with virtual IEP meetings. Ire Diaz, who oversees programs and services for The Advocacy Network on Disabilities in Miami, says her organization is “bracing for a lot of calls about financial assistance,” and she worries that helping students with disabilities with their online lessons will become even harder for parents if they lose their jobs.

The district has advised teachers that they should be available to their students for at least three hours a day while schools are closed, though teachers say they’re working much longer hours to learn the new programs and help their students and parents troubleshoot.

Casanas is planning to try out the new video chat software with her students Thursday — she’s hoping for a 10-minute check-in to say “I miss you” — and she is studying a new program that would allow her to assign her students passages that can be read aloud to them, since most of them can’t read. Then she could go over comprehension questions with them by video.

She’s hoping when students come back from spring break, she can start teaching them for a few hours in the morning by video, and then offer them one-on-one support in the afternoon on their computer programs. If that doesn’t work, she’s already thinking of “Plan B, C, D, E, F, G.”

“I’m going to try everything,” she said. “The main goal should always be just meeting our students’ needs. And that’s all we can do during this time.”

Matt Barnum, Alex Zimmerman, and Christina Veiga contributed reporting.