Teacher phone calls. “Daily meaningful interactions.” Check-in forms. Morning notes in Google Classroom.

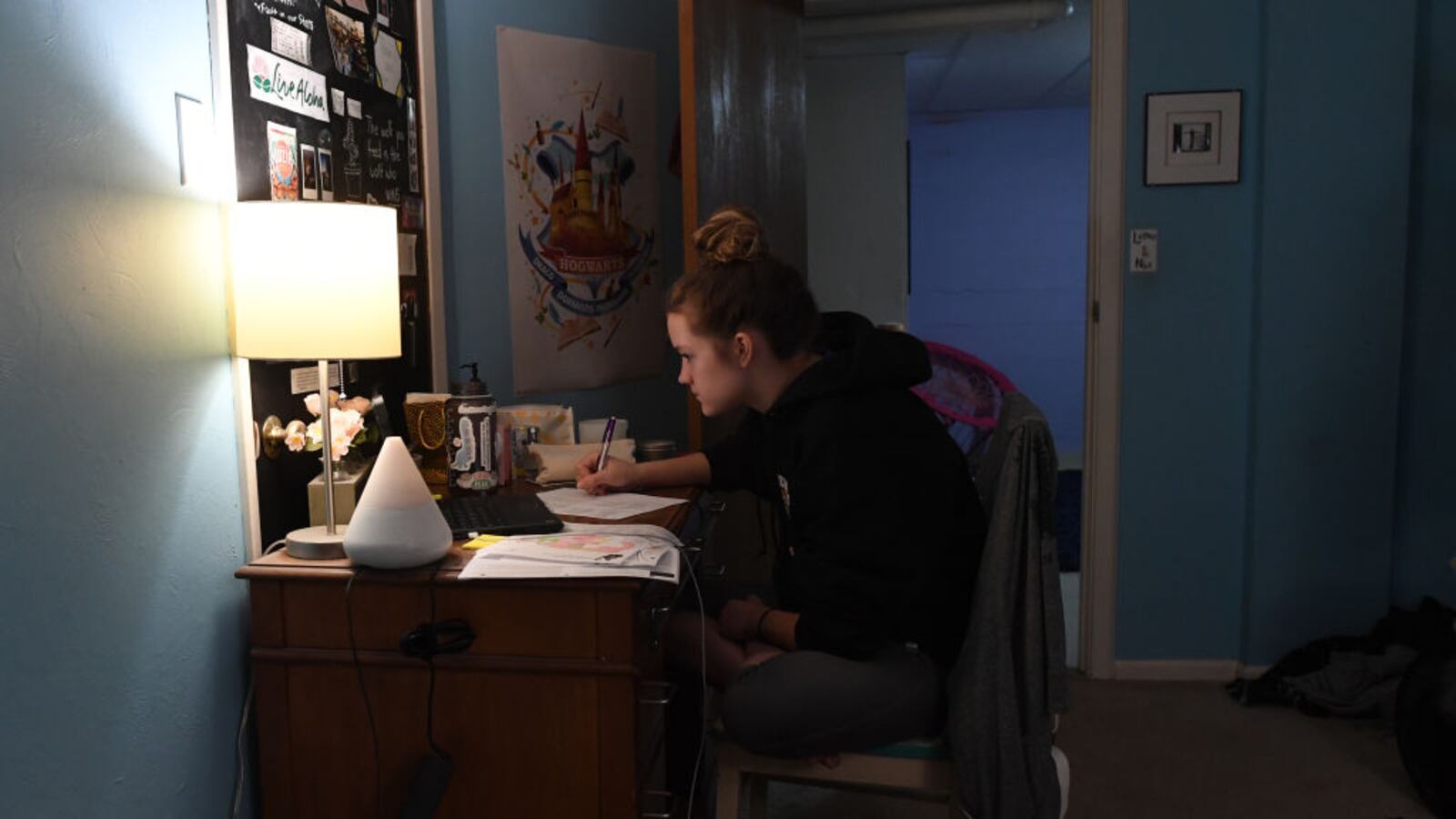

Taking “attendance” in America’s schools has never been more complicated. With school buildings closed nationwide, what once was a straightforward endeavor has become something of an anything-goes attempt to track whether students are engaged.

The stakes are high. Most students are poised to go without months of traditional instruction, and the learning losses could be significant — especially for those who don’t engage at all as schools attempt to teach remotely.

But many districts aren’t formally tracking student attendance, according to a new analysis by the Center on Reinventing Public Education and Chalkbeat reporting across the country. CRPE, which looked at 82 large districts’ public policies, found that just 14 are tracking attendance, though more districts may be tracking it without a posted policy.

That doesn’t mean schools and teachers aren’t checking in on students in some form — many say that they are. But no daily data means less information about which students need support right now, as well as which students are most likely to need extra academic support later.

“We’ve seen a lot of districts not have a policy at all or not be explicit about it,” said Betheny Gross of CRPE. Without good data, “How will we know who we need to apply some extra resources to reach and connect with in this time? Our kids are everywhere.”

Numbers out of Los Angeles were the first to illustrate the scope of the challenge of getting students engaged online. Forty thousand high schoolers hadn’t been in daily contact with teachers, the Los Angeles Times reported in late March.

The latest available data show that three in four high school students had logged in to the district’s online portal on an average day the following week, a district spokesperson told Chalkbeat. She did not disclose numbers for elementary or middle schools, and the district was on spring break last week. (Los Angeles does not consider this tracking attendance, and CRPE does not count the district as doing so.)

New York City schools began its attendance tracking effort last week. Teachers are counting “daily meaningful interactions,” which can include participation in an online discussion, a completed assignment, any response to a teacher’s email, or even communication with a family member that indicates a student is engaged.

The district has yet to release data. But at a press conference Thursday, Mayor Bill de Blasio indicated the initial picture would be worrisome. Teachers are “reaching a lot of kids,” he said, but “there’s clearly an issue with attendance.”

“We know a lot of kids aren’t logging on as much as we want them to,” he said.

In Denver, where remote learning kicked off last week, schools are also offering students a menu of ways to show they’re “present” each day, including signing an online form, logging into an online portal, or emailing a photo of work they’d done.

The district isn’t using this “for the purposes of any kind of punitive measures,” Denver Public Schools superintendent Susana Cordova said. It’s “really to make sure we’re engaged with our students. And when we are not seeing that students are engaged in learning, we can reach out to have conversations with families about supports that they need.”

Some large districts in Florida, like Miami-Dade and Broward counties, are taking a more straightforward approach. Students have to sign into an online portal daily, and a parent is notified if they don’t.

“The attendance data is used for us to provide intervention and outreach to students who are not connected,” said Robert Runcie, the Broward superintendent. “Folks aren’t getting a pass at this moment because we’ve shifted to the distance learning model.”

Runcie said it helped that the district already had a single portal where students could complete work and interact with teachers. Daily log-in rates are between 87 and 89%, he said, and students who don’t sign in are getting check-in calls to see if they have connectivity or other issues at home.

That kind of attendance tracking only works if students have a device and stable internet access at home. Many of the districts monitoring students daily have distributed thousands of devices to students and worked to pair families with free or reduced-price internet deals, though some students remain unconnected.

To make instruction accessible to more students, many school districts are offering non-virtual ways to engage in remote learning, which can make it harder to track daily progress. And some school districts say they’re letting individual schools decide how they’ll track attendance and student engagement, making it more difficult to use that information to come to any conclusions later.

In Chicago, which is officially launching its remote instruction effort this week with both online and printed work, the district will not monitor attendance daily, though officials said they would track whether students are turning in assignments.

Detroit has been providing printed academic packets to students and directing those with internet access to resources online. Officials have also committed to making contact with 100% of students. In Memphis, where lessons are being disseminated online, on public television, and via paper packets, teachers are expected to contact parents to check in on students. But neither district is taking daily attendance.

Hillsborough County in Florida, on the other hand, is taking attendance — but on a weekly basis. If a student logs into a web portal, completes a paper packet, or communicates with a teacher in any way, they are counted as present; students with no interaction whatsoever are marked absent. By this definition, in both of the first two weeks, nearly 99% of students were engaged, according to data the district provided Chalkbeat.

Still, it’s not obvious what to make of attendance figures like these. Some students could be learning in ways that aren’t picked up, while others may check in but do little else.

“Merely logging in does not tell us anything more than the student turned on their computer,” Los Angeles superintendent Austin Beutner said in a speech last week. “The absence of a log-in, when a student is reading a book or working on a writing assignment, can leave a misleading digital footprint.”

Meanwhile, educators across the country have reported going to extraordinary lengths to track down their students, regardless of their districts’ policies.

At University High School in Newark, New Jersey, Principal Genique Flournoy-Hamilton spends about an hour each day contacting students, particularly those who haven’t checked in on Google Classroom. A student support team — which includes a social worker, nurse, and attendance counselor — also calls students throughout the day, whether they’ve been marked present or not.

Many factors stop students from checking in, they’ve found. A student’s parent could be an essential worker who can’t oversee their schoolwork until later in the day, or the family might lack the technology needed for virtual learning.

Flournoy-Hamilton said the school has to balance its push for students to keep attending class remotely with a recognition of the burdens many are shouldering during the pandemic, such as working at grocery stores to help keep their families afloat.

“Not everyone’s family has a paycheck coming in,” she said, “so I can’t tell them not to go to work.”

Patrick Wall, Melanie Asmar, Alex Zimmerman, Mila Koumpilova, Lori Higgins, and Laura Faith Kebede contributed reporting.