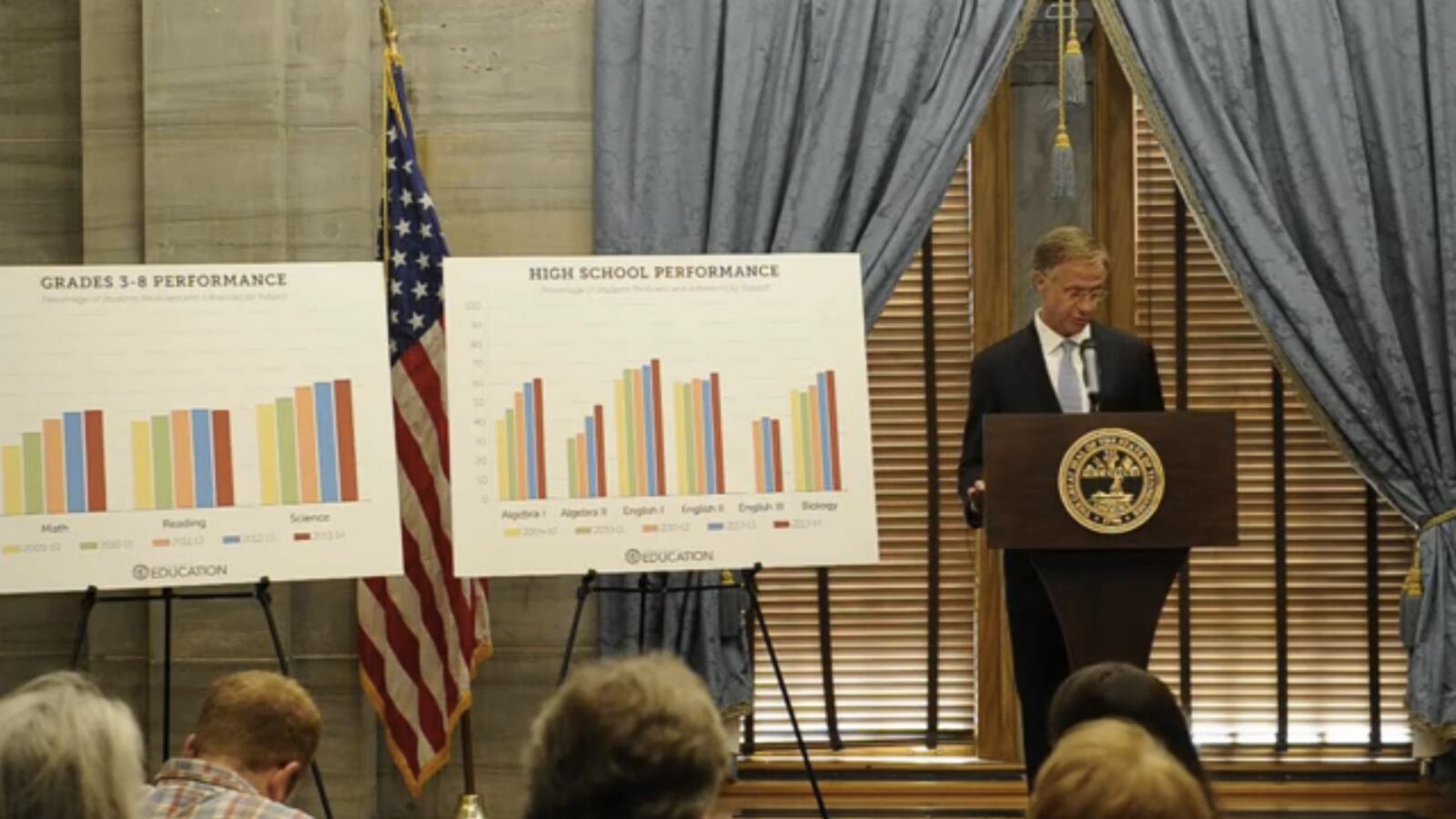

After a year in which lawmakers and educators heatedly debated which standardized tests should be given in Tennessee schools and how their results should be used, Gov. Bill Haslam and state schools chief Kevin Huffman cited sustained increases in test scores as evidence that the Common Core state standards and using data to gauge academic progress are improving education in the state.

For the fourth consecutive year, students’ scores on the Tennessee Comprehensive Assessment Program, or TCAP test, improved in most subjects, though at a slightly slower pace than in the past. And while achievement gaps among racial groups closed slightly this year, wide chasms remain.

As when the state posted large gains on a national exam last year, the officials credited new standards and changes to teacher evaluation policies with driving improvements in schools, while acknowledging that the state’s schools and testing program have room to improve.

“There’s no doubt that higher standards are making a difference in Tennessee,” Haslam said during a press conference in Nashville Tuesday morning.

Even Haslam’s critics on education saw good news in the scores. “It recommends all the hard work teachers do every day and the standards being implemented now,” said Gera Summerford, who recently finished her term as president of the Tennessee Education Association (TEA).

But the state’s education policies, and Huffman in particular, have increasingly drawn fire. Since September, separate groups of superintendents, teachers, parents, and legislators have each challenged Huffman’s policies and called for his resignation.

The Common Core and use of student data drew particularly fierce criticism this spring: Tennessee’s general assembly voted to postpone the use of the PARCC Assessment, a test specifically aligned to the Common Core standards, for at least one year, prohibited the state from adopting common standards in additional subjects, and debated whether to back away from the Common Core standards altogether.

Legislators also passed a law stating that data can only be used to track students’ academic progress, limiting its use for research purposes and attempting to assuage parents’ concerns about privacy. Scores were also prohibited from being used to determine whether a teachers’ license should be revoked. Teacher advocacy groups in the state have raised concerns about the validity of using students’ scores to measure teacher and school performance.

Haslam said today that data is necessary to spotlight areas where the state still needs to improve. “There are folks who want to minimize the use of data in education. I strongly feel they’re doing a disservice to our students,” Haslam said.

But how far individual schools and districts have come will not be clear until the state releases more detailed results later this month.

Those more granular results will have big implications for students, educators, and schools. Up to 50 percent of teachers’ evaluations are based on “measures of student success,” which include students’ improvement on test scores. And the scores are worth up to 25 percent of a student’s end-of-year grade in some courses.

A 2011 federal Race To The Top grant and set of laws known as the First To The Top law pushed the state’s education department to use test score-based data to target resources and efforts. Any school ranked in the bottom 5 percent in the state is subject to takeover by the state-run Achievement School District (ASD) or district-level turnaround efforts that involve replacing all teachers at a school. Schools with large gaps in the performance of different groups of students are also singled out for attention as “focus schools.”

Those results will also allow for a closer analysis of how those state-supported school improvement efforts, including the ASD and efforts to retain teachers in low-performing schools, are going.

Shelby County board member Shante Avant said last month that the scores will provide a referendum on some of the policies promoted by the state. “How the Achievement School District does compared to the Innovation Zone will be really interesting,” she said. Last year, the state district’s test scores did not grow as quickly as scores within the district’s turnaround zone. “If the ASD is not doing well again, maybe that means the state needs to think about its policies,” she said.

Even as the governor and education commissioner touted today’s scores, Huffman and other education advocates said there are better ways to measure students’ performance than TCAP.

Huffman implicitly criticized state legislators’ move to delay PARCC tests, which, unlike TCAP, were designed based on the Common Core and require students to provide their own answers to some questions. “One of the challenges our teachers have grappled with is working with with higher standards, teaching [students] how to grapple with critical thinking…while at the same time we’re giving an assessment that’s a multiple choice test,” he said.

Others suggested that the problem was relying too heavily on any one standardized test. J.C. Bowman, the executive director of the Professional Educators of Tennessee, said that the state tests provide only a limited snapshot of what happens in a classroom.

“It’s like your school pictures,” he said. That’s the way you looked that day, whether you like it or not. It doesn’t mean that’s how you always look.”

Summerford echoed that concern. “These scores all alone don’t tell us everything we need to know about schools and classrooms. They’re just one piece.”