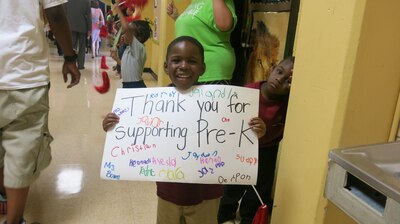

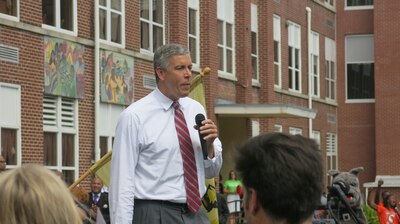

Efforts to improve historically low-scoring schools in Memphis were in the national spotlight Wednesday as U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan ended his back-to-school bus tour of southern states with a pep rally and town hall meeting at Cornerstone Prep, a charter school that’s part of the state-run Achievement School District.

Duncan said he chose to end his tour in Memphis in order to “look at the turnaround work that’s happening there and the overall improvement in schools.”

At the town hall at Cornerstone Prep, Duncan told a crowd, “I want you to understand the possibility here… If you can, for all the challenges of poverty and history—if Memphis can break through, what kind of message does that send to the country? I want people to seize the moment, seize the collaboration. Keep your eyes on the prize. If you stay the course, you’ll stun the world.”

After the meeting, Shelby County superintendent Dorsey Hopson II said he hoped some of the national attention being paid to education in Memphis would be echoed in town. “I can’t go anywhere without hearing about Memphis and education,” he said.

Duncan, Hopson, ASD superintendent Chris Barbic, principal Lionel Cable of Shelby County school Douglass K-8, Cornerstone teacher Brittany Ordue, and Cornerstone parent Yolanda George participated in a question-and-answer session led by Reggie White, the director of Streets Ministries, a local nonprofit.

Both Barbic and Hopson specifically emphasized collaborative efforts between the ASD and Shelby County Schools. They also raised concerns about finding and retaining enough teachers to work in low-performing schools and about scaling up successful efforts.

The districts were touting results from last school year’s state standardized test: While scores within each district were mixed, there are 4,500 fewer students in Memphis attending schools ranked in the bottom 5 percent in the state based on their test scores this year than in 2012. And while low-scoring schools’ scores had hovered around 16 percent proficient on state tests in 2012, they are now closer to 25 percent proficient. Tennessee also was rated the fastest-growing state in the country on the National Assessment of Educational Process last year.

Hopson said the district has been focusing on teacher effectiveness, early childhood education, and literacy. He also singled out “our relationship with Mr. Barbic and his team…as he likes to say, we’re in ‘co-opetition.’ When you bring people together where the agenda is what’s best for kids, you see the successes we’ll talk about today.”

Barbic echoed the sentiment. “There’s not a city I can think of when you can pack a room like this where you don’t have people lobbing bombs…charter and non-charter, we have to come together to get this done,” he said.

“We have one common enemy—academic failure. We all have to work together to eliminate failure,” Duncan said.

When asked what led to improvements in test scores at his school, Cable, the principal at Douglass K-8, a school in Shelby County’s Innovation Zone, pushed back against a common buzzword: “There’s no innovation there, just really rich, very strong teaching. If you introduce innovation—people put it out there but they don’t talk about sustainability,” he said. Innovation Zone schools received federal School Improvement Grant funds, longer school days, and more flexibility in hiring staff.

“We’re supposed to race to the top. But sometimes it’s okay to come in last as long as we’re doing what’s right by the children,” Cable said. A 2011 Race to the Top grant—one of Duncan’s education department’s signature programs—funded the creation of the ASD. Several changes prompted by the grant, including tying teachers’ evaluations to test scores, have drawn the ire of the state’s teachers’ union and some district leaders.

Duncan said that while Race to the Top had been significant, his department had spent more on school turnaround programs such as the Innovation Zone schools. The federal School Improvement Grant program has had mixed results nationally; Duncan recently expanded the options for districts seeking to use federal dollars to turn around schools.

The panelists fielded questions about how to expand successful school turnarounds.

“That’s the million-dollar question,” Barbic said. “How do you take pockets of excellence and scale them?…That comes down to how Dorsey and I work together to be strategic with our resources.”

“What we’ve found, particularly in turnaround schools, is that the most important thing is to have a strong leader, a strong group of teachers who beieve all kids can learn,” Hopson said.

Cable said that in his experience, “it’s certainly not the money…The important thing is for principals to have the autonomy to make decisions in the best interest of kids. I think that can be duplicated, but the handcuffs have to come off.” He said he had used the extra funds his school received to hire quality teachers rather than on new technology.

Keith Williams, the president of the Memphis Shelby County Education Association, asked Barbic whether the ASD, which aims to turn around schools in the bottom 5 percent in the state, would always exist. Barbic said that while the legislation that created the district did not specify, he thought the ASD would be around until the bottom 5 percent was scoring well above where it was when the district was created.

Duncan said that he was concerned that most districts were not sending their best teachers to the neediest schools. Barbic pointed out that Shelby County’s I-Zone schools only hire teachers who have earned high scores on evaluations. “But the question is then how do you backfill to other schools?” Board members and administrators in the district have echoed this concern.

He said that districts and schools need to figure out “how to make sure teaching doesn’t feel like a two-three year thing on the way to something else. How can teachers feel like they can grow?”

The panelists were near-unanimous on the last question: When White asked what gave them hope for the city’s future, each said the city’s students inspired them.

“I moved to Memphis thinking I’d change lots of lives every year. But really, my life has been drastically changed,” said Ordue.