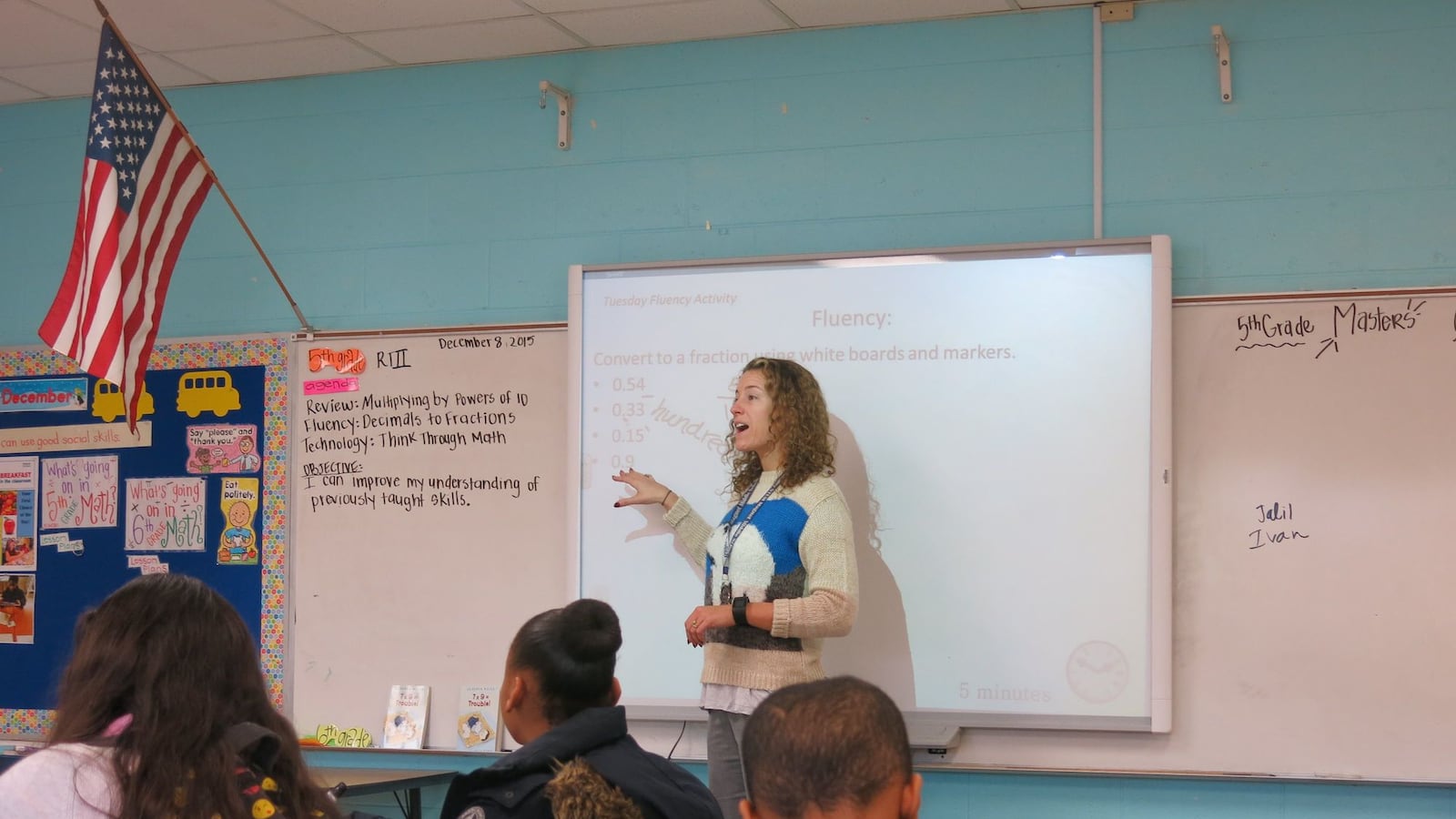

Nashville teacher Karen Wolfson remembers when her principal offered an unexpected observation: She wasn’t asking questions that made her students think.

Now, before class even starts, Wolfson makes lists of probing questions she might ask in class. It’s a simple change that doesn’t take much time, but it makes a big difference in the classroom.

“I’ve definitely been like, ‘Wow! This makes it a lot easier to go deeper,’” said Wolfson, now an instructional coach at Bailey STEM Magnet Middle Prep.

On the other side of Nashville, middle school teacher Amanda Kail recalls overseeing an experiment in which her immigrant students observed birds in order to practice scientific language in English. The kids loved it. But then Kail got the second-lowest score on the state’s teacher evaluation system, and the number of district practice tests increased. She scrapped the project.

“We’re told, ‘Don’t teach to the test! We want our classes to be vibrant places!’” said Kail, who teaches English language learners at Margaret Allen Middle Prep. “But the reality is, your evaluation is based on those test scores. That’s a double message.”

Such classroom experiences are an outgrowth of Tennessee’s concentrated push to better train teachers, evaluate them and hold them accountable for helping children learn. They also reflect some of the tensions underlying the state’s education policymaking during the last five years.

Fueled by a half-billion-dollar influx of federal education funds, the state invested more money than ever to help teachers reach their students as part of a massive overhaul of Tennessee’s K-12 public education system. It also raised the stakes of the standardized tests that many educators say undermine good teaching.

Those funds, which flowed through the U.S. Department of Education’s Race to the Top competition, dried up this year. What’s left behind are higher-than-ever consequences for student test scores, which Tennessee teachers are now trying to reconcile with the changes in teaching that the state has pushed.

“On one hand, teachers are told to embrace the standards and a different way of teaching,” said Marcy Singer-Gabella, a researcher at Vanderbilt University who helps run a charter school in Memphis.

“And on the other hand, they’re being pushed toward traditional, directive instruction through testing,” she said. “If you’re going to be paid based on this, what are you going to choose as a teacher?”

First to the Top, and first to change teacher evaluations

Race to the Top was the U.S. Education Department’s strategy for influencing states at a time when Congress was unwilling to revise federal education law and the economic recession was hobbling state budgets. The department told states that they could win part of $4.35 billion in new funds as long as they committed to the department’s priorities.

Those priorities included shared standards, or expectations of what students learn and when they learn it; improving the lowest-performing schools; measuring students’ growth over time; and designing policies to reward and retain top teachers. Practically speaking, many states combined the student growth and teacher quality requirements to promise teacher evaluation systems that weighed student test scores.

As their counterparts did in many states, then-Gov. Phil Bredesen and the Tennessee legislature aggressively pursued the funds, galvanized by a 2007 U.S. Chamber of Commerce report that gave the state an “F” for its lack of high standards and assessments in the classroom. They called a special session to enshrine almost all of the necessary provisions in a state law called “First to the Top.”

The law established Tennessee’s Achievement School District, allowing the state to intervene in low-performing schools at an unprecedented level. It adopted the Common Core State Standards for math and English. It required annual teacher evaluations that incorporated student test scores.

“The stars have aligned this year to create opportunities to make significant improvements in public education in Tennessee,” Bredesen told lawmakers to kick off the special session. “When that happens, we’re obligated as public officials to seize the moment. That moment is now.”

Tennessee was one of the first Race to the Top recipients when it won the grant in April 2010, three months after First to the Top became law. Half of the money was distributed to districts to spend as they pleased. The other $250 million was to be spent on statewide changes designed to revolutionize Tennessee education.

When Bill Haslam became governor in 2011, he vowed to continue Bredesen’s education policy agenda. He quickly tapped Kevin Huffman, a lawyer and Teach For America administrator, as his education commissioner and charged him with implementing the state’s Race to the Top promises.

Huffman’s strategy was to weave the disparate policies required under the grant into a single push to improve teaching. Unlike other Race to the Top recipients, he implemented teacher evaluations that incorporated student test scores swiftly, as promised in the state’s Race to the Top application.

“We were very firm that, hey, instruction matters. It matters now, it matters during the transition, it matters after the transition,” Huffman told Chalkbeat this year, months after resigning as education commissioner. “The evaluation was about continuing improvement. And by doing evaluations and having them count so people took it very seriously, we were really able to get the continuous improvement cycle going.”

The race to transform teaching

Nashville’s Bailey Middle was among schools that benefited from Race to the Top-funded initiatives early on. As part of a special effort aimed at improving the state’s lowest-performing schools, it got extra money to attract talented teachers and to create “teacher-leader” positions to get top educators helping their colleagues. And many of its teachers came from a Vanderbilt University master’s degree program funded by Race to the Top and aimed at producing leaders for urban schools.

Christian Sawyer had been a teacher in residence at Vanderbilt when its urban learning program was created. When he became principal at Bailey in 2012, he immediately began taking advantage of state training sessions funded with federal money.

Those trainings were a linchpin of Tennessee’s Race to the Top-funded initiatives — and where more than $40 million of the winnings went over four years.

During the 2012-2013 school year, more than 40,000 teachers — or about two-thirds of the state’s teaching force — attended the voluntary trainings, which were conducted by experienced teachers who applied for the opportunity. Most of the sessions focused on Tennessee’s new academic standards, the Common Core, which the state had adopted along with 45 others in an effort to create shared expectations for student learning for the first time.

Since Common Core aims to deepen higher-order thinking skills and student-driven learning, the training sessions encouraged teachers to incorporate hands-on projects and group work in their lessons instead of lecturing. (In a dynamic that is playing out in many states, political pressure has since led state officials to revise the standards and drop the Common Core name, but they say they do not plan to abandon the principles behind the standards.)

At the trainings, teachers learned how to encourage students who don’t pick up new skills right away and how to help students organize their thoughts before writing an essay, among many other instructional techniques. Coaches emphasized “differentiated learning,” in which teachers tailor instruction for every student’s individual needs.

Brian Moffitt, a social studies teacher in Obion County, said he experienced an “aha” moment when one training leader asked teachers to recall their favorite class from their student days. His had required him to defend his own ideas, requiring critical thinking — one of the core tenets of Common Core. So when the new school year started, Moffitt incorporated more hands-on art projects into the curriculum, and cut back on his lectures.

“[The projects] really allowed me to see what they were doing and learning,” he said.

Other trainings were designed to help educators navigate the state’s new evaluation system, known as TEAM. Those sessions were meant for principals and other school administrators, but Sawyer sent some of his teachers, too — to great effect.

“The TEAM rubric was a springboard for rich conversations,” Sawyer said. At Bailey, teachers coach each other based on their strengths and weaknesses on the rubric, which covers areas such as student motivation, lesson planning and grouping students. The specificity has helped even experienced teachers figure out ways to improve.

Huffman says shifts like the one Moffitt described are unfolding across the state.

“You are far less likely to walk into a classroom today and see no instruction and see people doing nothing useful,” he said. “I think you are more likely to see people who are teaching to group discussion, critical thinking, engagement, student-led.”

Outgoing U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan praised the state’s education policy efforts during a recent visit to Memphis.

“Tennessee has done many, many things well,” he said “While we are proud to have invested in Tennessee, I want to be clear. Our money is a tiny, tiny part of the story. This is about leadership, this is about courage, this is about high expectations. This is about adults doing this hard work every single day.”

Increased influence of test scores spurs urgency — and fear

While the highly touted federal competition was meant to take Tennessee to the top, the state has managed to move from the bottom to the middle of the pack, based on scores from the last two Nation’s Report Cards. Tennessee students still lag behind their counterparts in many other states on nationwide exams, and Huffman said one reason is that instruction is not where it needs to be.

“I still think there are a lot of times when you will walk into a classroom and see teachers standing in front, teaching from the textbook,” Huffman said. “I think we have given a lot of willing and able teachers tools to teach better, but I still think we have a wide range in instruction.”

It was that range that motivated state officials to overhaul the state’s teacher evaluation system. Federal officials and Tennessee lawmakers alike were struck by the fact that teachers routinely received positive evaluations even as their students struggled on state and national tests — and that many teachers were not evaluated at all. They wanted to be able to reward teachers whose students made progress and remove teachers whose students fell behind.

“I know this represents change, but this is not rocket science,” Bredesen told legislators in 2010. “It is a common-sense notion. We pay teachers to teach children; a part of their evaluation ought to be how much the children they teach learn.”

To figure that out, state education officials turned to an esoteric formula that they had used since the 1990s to calculate how much teachers contributed to their students’ test score gains each year. The Tennessee Value Added Assessment System, known as TVAAS, aimed to show how much teachers impact students’ test scores. But the state calculated scores only for diagnostic purposes; they didn’t actually come with consequences. In fact, Tennessee law virtually prevented TVAAS scores from being used to evaluate teachers.

Aided by the state teachers union’s decision not to block a potential funding boost despite longstanding concerns about TVAAS’ accuracy, Bredesen convinced the legislature to roll back the prohibition on using the measure to reward or penalize teachers. In the end, First to the Top mandated that 50 percent of teachers’ ratings be based on student achievement data: 35 percent based on TVAAS — or “some other comparable measure of student growth” for teachers whose students did not take state tests — and 15 percent to be determined by the evaluator and teachers from a list of options including school TVAAS data.

While other states hesitated before including test scores in teacher evaluations — even states that had promised to in their Race to the Top applications — Tennessee included value-added measurements from the start. When teachers received their first ratings in 2012, up to half of their score reflected their students’ test score gains.

A new incentive for low-performing schools

Tests became more important to districts for other reasons, too.

Tennessee had administered annual tests since the early 1980s. But after Race to the Top, test scores — and specifically TVAAS — held sway over teacher evaluations, and which schools were eligible for state takeover by the Achievement School District.

Schools and districts were motivated more than ever to turn around low-performing schools on their own, although they also had more resources than ever to do so.

“The ASD has created this sense of urgency that may not have been there,” Shelby County Schools Superintendent Dorsey Hopson said this summer.

Efforts to increase student performance included the implementation of “innovation zones” in Memphis, Nashville and Chattanooga, where principals were given more autonomy to hire and fire staff, overhaul curriculums, give their teachers bonuses, and add time to the school day.

But the emphasis on student performance also meant that districts increased the number of practice tests, to ensure students were prepared for end-of-year exams.

And a rubric that was supposed to help educators talk about how to improve also had some unforeseen consequences.

At schools where administrators understood TEAM’s goals, educators gained a new language and toolkit for talking about instruction. At Bailey, administrators used the evaluation system’s rubric to open low-stakes conversations with the teachers they supervised. They also used the ratings to pair teachers with different strengths and weaknesses so they could learn from each other.

But the level of bureaucracy also increased, as teachers labored over lesson plans that fit all of the evaluation’s criteria — sometimes taking away time they would have spent with students. Some of the items on the checklist — like stating the learning objective three times throughout a lesson — don’t always feel natural to teachers.

“Sometimes you have to put on your dog-and-pony show,” said Laura Wilons, a teacher at Grahamwood Elementary in Memphis. “It can feel ridiculous.”

Whitney Bradley, a literacy coach at Bailey and Metro Nashville’s 2015 middle school teacher of the year, said she found the evaluation process mostly rewarding, in large part because of Sawyer’s leadership. But even at Bailey, with a principal who didn’t get bogged down in parts of the rubric that seemed arbitrary, the process could be overwhelming at times.

“When you look at all the things that make you a Level 5, it can inundate you,” she said. “And you can be so consumed with making sure you did this and did this, and you can forget about being a teacher.”

Huffman said he is aware of the limit and misinterpretations of teacher evaluations. In retrospect, the state could have benefited with more training on teacher evaluations — especially of teachers, so they have the opportunity to understand its nuances and the spirit behind it, like the teachers at Bailey did.

“If there’s one thing I could change, I’d go back in time and do that,” he said.

Path forward will be marked by testing

It’s unclear if funding for the instructional training that gave Brian Moffit his “aha” moment will last beyond next summer, now that Race to the Top funding is fully spent. Tennessee Education Commissioner Candice McQueen, who replaced Huffman in January, has asked for $3.5 million to keep training teachers in new instructional strategies, but it wouldn’t be for the large-scale summer trainings that brought educators together in the past. Instead, coaches would be trained and sent back to districts.

For the most part, the state is leaving it up individual districts to figure out how to sustain ongoing initiatives kicked off through Race to the Top.

What remains are the tools that Tennessee built using what Huffman calls “one-time” expenditures with Race to the Top funds. Those include the state’s education data infrastructure and its teacher evaluation system.

Also set — at least for now — is the state testing program and the role it plays in the way teachers and schools are graded.

Nationally, concerns are mounting about the role of testing in schools, and Tennessee has seen its share of pushback. Last year, Haslam paused a policy that allowed TVAAS scores to count in licensing decisions. This spring, legislators temporarily reduced the weight of test scores in teacher evaluations. A task force that McQueen convened recommended that districts reduce the amount of practice testing that students experience. The state also is exploring more portfolio models for teacher evaluations of non-tested subjects — meaning that teachers can find alternative displays of their teaching, instead of using schoolwide test scores, for their evaluations. And changes approved last week to federal education law would let states rely on factors other than test scores when deciding which schools to try to improve.

But even amid signs that the pendulum of education policy is swinging away from test-based accountability, Tennessee appears poised to continue its basic trajectory.

After all, given flexibility in the past, Tennessee has continued to stay the course on its testing policy. When Arne Duncan said states could delay the use of test scores in teacher evaluations during standards and testing transitions, Tennessee declined.

Test scores are set to return to their previous weight in teacher evaluations — 35 percent — within two years.

In addition to being committed — to the tune of $107 million over five years — to end-of-year testing that is required under federal law in third through eighth grades, Tennessee is looking for vendors for a new optional test for even younger students in the coming years.

"There’s always a healthy tension between accountability and … instructional freedom."

Sara Heyburn, State Board of Education

And although McQueen has indicated that she supports her task force’s recommendations to reduce practice testing, the state remains committed to frequent, short benchmark tests for a program called Response to Instruction and Intervention, or RTI, that aims to help more students meet the state’s academic standards — and pass tests — by providing teachers with more data on students’ strengths and weaknesses.

State officials concede that current education policies might give footing to the “double message” theory described by Kail. But they’re counting on newer and better tests — the Common Core-aligned exams launching this year under the name TNReady — to resolve the tension.

“There’s always a healthy tension between accountability and … instructional freedom,” said Sara Heyburn, director of the State Board of Education and a former assistant state education commissioner who rolled out the teacher evaluation system. “I think it’s one of the reasons why it’s important to move toward tests that are authentic.”

For the new tests, “your test prep is great teaching and learning,” McQueen said earlier this year.

That’s not what teachers at Bailey in Nashville say they are experiencing. A year after making the largest math gains in the city, the school has changed significantly.

The leadership program that attracted many of the teachers to the school ended after its Race to the Top funding ran out. And when Sawyer moved to Denver, Colo., to head a school there, he took with him knowledge from state training sessions that helped teach him how to offer helpful feedback to his teachers.

Now, the school is adjusting its instruction once more, to make way for TNReady practice tests that Metro Nashville Schools is requiring this year. That leaves less time for the type of instruction officials and teachers agree is best.

“We just can’t teach things as deeply as we used to,” Wolfson said.

The argument that TNReady is a superior test that asks students to demonstrate more relevant skills than Tennessee’s old tests is little consolation for teachers at the school.

“It’s debilitating, because no matter how much you teach, no matter how much you incorporate differentiated learning, RTI — it’s still one test. One day,” Bradley said. “And that’s almost antithetical to the educational push they have right now.”

She added, “If the basic premise is that one or two tests show a student’s progress, we will never get better.”