Chris Barbic is navigating one of his most challenging seasons as superintendent of the state’s Achievement School District (ASD).

Tasked with turning around schools ranked academically in the bottom 5 percent of Tennessee’s public schools, the district is completing its third year of operation in what Barbic calls a “battleground state” in the education change movement. Most of the priority schools under ASD oversight are in Memphis, where community loyalty to neighborhood schools is fierce. Last year, the ASD’s process of taking control of struggling schools – and then transitioning them to charter schools – proved contentious, with protests and three charter operators pulling out of school matches.

While the ASD appears this year to have weathered a bevy of bills in the state legislature aimed at scrapping the ASD or limiting its authority, it’s still smarting from the withdrawal last month of nationally heralded YES Prep, five months before the charter school network was to assume control over one school in south Memphis. The exit was particularly thorny for Barbic because he helped found YES Prep in 1998 and led it to national prominence before leaving Houston to head the ASD.

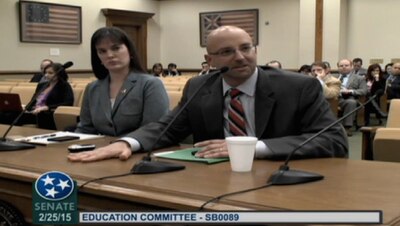

In an interview with Chalkbeat, Barbic, 44, talks about the difficult work of turning around struggling schools, the lessons he’s learned while shepherding Tennessee’s pioneering turnaround district, and his message to the nation’s education community about change and improvement. Here are the highlights:

There’s a huge educational experiment going on in Tennessee, and it’s called the Achievement School District. But most Tennesseans aren’t even aware of the ASD and its significance in big-picture education conversations across the nation. How would you explain what the ASD is and what it’s trying to do in Tennessee?

The ASD is a statewide school district that’s focused on the priority schools that are defined as the bottom 5 percent in the state. Our job is to improve outcomes in those schools. We’re doing that in three ways: first, authorizing great [charter] organizations to run the priority schools; second, pushing the autonomy and resources down to those educators that are running the organization so they’ve got the authority to make the decisions that matter most around educating the kids; and third, holding them accountable for results. We believe that by partnering with the organizations, giving them the resources and autonomy to be effective, and then holding them accountable for results – that’s the best role we can play as a state-level district to ensure that kids are getting a better quality education than they’ve been receiving.

Whenever a state wrests control from a school or local district, it’s got to be difficult for everyone. In Memphis, for instance, the ASD now oversees 22 schools that once were under the purview of Shelby County Schools. How do you work with the local district to keep this relationship constructive during the turnaround process?

Well, I think you’re right. It is difficult. I think part of it is starting with acknowledging that from the beginning. When I took this job in 2011, I took it knowing full well that there would be situations where we would butt heads or not see eye to eye with the local district, and that was going to create some tense conversations. I think my biggest surprise has been the degree to which, especially in Shelby County, adults have been able to put kids’ interests first. That goes all the way back to Dr. [Kriner] Cash when he was superintendent. We’ve built an even stronger relationship with [Superintendent] Dorsey [Hopson] and the folks on his staff. There are times the relationship gets portrayed in the media as a combative one. And there are times when we disagree and that’s just the nature of the work. Much more often than not, we work together. When things come up, we talk and we hash it out. It’s easier to do that because I know in my heart that Dorsey is there because he wants to do what’s right for kids. I think if you ask him, he’d say the same thing about me. We are both clear about what our agendas are. And when you have a partner whose intentions are pure, it’s much easier to handle dissension or times when you don’t agree because you know the other person is coming at this from a good place.

This year, there were at least 22 bills in the state legislature aimed either at doing away with the ASD or significantly limiting its authority, which certainly is a reflection that not everyone is a fan of yours. What is your response to the legislators and constituents behind these efforts?

I haven’t talked to all of the politicians who have sponsored these bills. I’m going to give everybody the benefit of the doubt and assume that they’ve got reasons for why they’re doing this and they think it’s the right thing to do.

Do you think they are jumping the gun?

[The ASD] is only three years old, so I think limiting it at this point is a little premature. We’re talking about schools that have in some cases been struggling for decades. To expect folks to come in and fix it in two years is a bit unrealistic. If it were that simple, it would’ve happened already. This is hard work, and I think we need to honor the folks who have raised their hands and said, ‘You know what? I want to go into schools and work with some of the most vulnerable kids in the state.’ We need to give the teachers and leaders in the building the space and time to be successful. For us, that means three years.

I would also point to the progress already happening. Look at the progress in the iZone schools and the ASD schools over the course of the last two years. Look at the energy around the philanthropy and the investments that are happening in priority schools across Memphis. Look at the talent partners that are coming to the city and getting involved in this work. So I think there’s enough to point to and say, ‘Let’s give this time.’ I’m really optimistic. I’m more optimistic now than I was even before we started. Not only are we making progress, but we’re already seeing a lot more kids in a lot more schools achieving at a much higher level than we’ve seen before all of this started. There are 4,500 fewer students attending priority schools today than there were just two years ago because of the collective effort happening in Memphis. And I think that the pressure we’re putting on the system and the pressure we’re putting on ourselves is making everybody better. It’s hard at times, but it’s making everybody better and kids and families are benefiting as a result.

If you could do it over again, would you pick the goal of taking schools in the bottom 5 percent to the top 25 percent within five years?

I think it’s the right goal. And here’s the reason: I think that if we were to go back in time, had we not stuck our flag in the ground at top 25 percent in five years, then we could’ve defined success in a lot of different ways. We could’ve said the ASD is successful if we get our schools out of the bottom 5 percent. We could’ve gotten a school in the bottom 7 percent and declared victory. To me, a school that’s off the list but still in the bottom 7 percent or bottom 10 percent is not a school that’s really preparing kids and giving them the kind of education they deserve. For us, this is about [setting] a goal that is ambitious, noble, and that’s going to get our schools to a point where any one of us would send [our children] there. I’m sure that in five years, if not every single one of our schools hits this mark, we’ll pay a price. But I also know that by us setting that benchmark, we’re pushing ourselves and the district much harder than if we said we’re just going to get out of the bottom 5 percent.

How would you describe your relationship with Memphians?

I think it’s a complicated relationship. And I think it’s a growing relationship. In the work that we’re doing, we’ve really tried to honor Memphis and Memphians, especially when you get away from the headlines in the media and you talk to parents at our schools and you hear stories about how much better they feel about their school as a result of this work. Building relationships takes time. The analogy I always use is that microwave food is never as good as home-cooked food. Relationships work the same way. You can’t come in and microwave relationships and have them be meaningful in just a couple of years. Building strong ones takes time. What I hope we’re demonstrating is that we’re going to keep showing up and we’re going to keep having conversations about this work and how we get better. And yes, there will be times when we make a mistake. We said when we started this that it isn’t going to be perfect. Most importantly, when we do make a mistake, we’re going to say we screwed up and we’re going to learn from it and get better.

To be clear, my expectation isn’t that parents are going to jump up and down and say “Yay, ASD!” at the very beginning of this process. I think a more realistic goal is for parents and communities to demand something better and to recognize that they deserve better than what’s been happening in their schools. What we’re saying is we’re going to work hard at this and we need to be held accountable too. And if we’re not getting the job done, we need to be held to the same standards we’re holding local districts to. To me, that’s a fair request.

What are some lessons learned?

I think we are learning a lot. But you have to keep in mind that we only have two years worth of data. If you look at last year’s data, our phase-in [in which schools are transitioned into charter schools one grade at a time] schools did well. As much controversy as phase-ins cause, just look at the results. Last year at our phase-in schools, you saw 22-point gains in reading and 16-point gains in math. At least initially, that’s better than what we’ve seen when we do the whole-school conversion. We still expect our whole-school conversions to meet our goals but are learning that their path getting there may look different. Our position is that we want our charters to make the decision regarding how they grow their school. And if they feel committed to doing phase-ins, we’re going to support them in that work. If they are committed to whole-school conversions, we support that too.

I think a second lesson is around the depth of the poverty in Memphis and the obstacle that creates in educating our students. Obviously, when we looked at the info on our kids before bringing a school into the ASD, we knew most of the kids we serve are living in poverty and that poverty plays a factor at school. I’ve been doing this for over 20 years and every single school I’ve worked with has been in a community dealing with poverty. But the poverty in Houston, where I worked before coming to Tennessee, compared to the poverty in Memphis, is different. In Houston, it was more of an immigrant poverty. In Memphis, it’s more generational poverty. I think that the depth of the generational poverty and what our kids bring into school every day makes it even harder than we initially expected. We underestimated that. To address it, we’ve worked hard to develop partnerships with organizations that provide wraparound and social service supports to our students and families. We still have work to do, but I believe we are making good progress.

Lastly, it’s important to have a pipeline of teachers and school leaders who are going to be able to do this work in a sustainable way. That’s as much a question as it is a lesson learned. Asking someone to come in and spend their career in a priority school, given the level of intensity required day in and day out to be successful, is a lot to ask of any educator.

Shelby County School leaders are having to offset a $125 million budget deficit next school year and have partly blamed the projected loss of an additional 2,657 students to a growing crop of charter schools and the ASD. Do you think you are responsible for the district’s budget woes?

The dollars follow the kids. So when a child becomes part of the ASD, we take responsibility for providing for those kids. I think that it comes back to fixed costs vs. variable costs. If the number of kids you are serving shrinks, then you would think that the teachers and all the supports required to serve that smaller number of kids should also shrink. The central office needs to be smaller when you’re serving fewer kids. But I would argue that should probably happen anyway. I believe in bottom-up vs. top-down. So if you buy this idea that people in the schools need to be making the decisions that matter most around hiring, budgeting resources, determining programs and determining the length of the school day, school week and school year, then you shouldn’t have massive fixed costs at the central office. We’ve got a small support team in the ASD. We’re going to be serving 10,000 kids next year. Our district’s central office will probably never go beyond 30-40 people. So, I get that it’s tough, and I get that budgets are shrinking. But I think if you zoom up 30,000 feet, for the city, it’s not going to end up resulting in a net loss of resources or positions. What’s happening is a shift. There are resources and jobs shifting from a [district] monopoly provider of schools to a lot of different organizations that will be operating schools. And we need to concentrate less on what type of school it is and more on the quality of the education each school is delivering to its students.

There are a lot of educators and policymakers across America who are closely watching the ASD and its outcomes. Some states, such as Georgia, Nevada and Texas, are looking at similar approaches to address underperforming schools. And there are several large research projects tracking your every move. At this point, what are they seeing? And what message would you like to send to the national education community?

On the positive side, people are not only recognizing we can no longer accept a low level of performance in our schools, legislators and policymakers are taking bold action in addressing our most struggling schools. We’ve got to get the education right if we as a country want to maintain our stature in the world. And just educating the top half of kids to high levels is no longer good enough. Setting up state-run districts focused on priority schools creates energy, focus and urgency in creating a quality education for students that have for far too long been ignored or neglected. All of this is extremely important and good. But in education, we tend to look for silver bullets and we need to be conscious that setting up ASD-type organizations doesn’t turn into the next silver bullet in the reform community. Every time a state does this, it is important that it works well. During the first decade of charter schools, for every good charter, there were five lousy ones. But if we are setting up achievement school districts, every one of these needs to be good. We can’t be in a situation where for every one state that does this well, five states screw it up and get it wrong. It is why these studies and research projects are so important. Lessons we learn can easily get captured to help other states set these up effectively, get it right, and help even more of our students and families.

The ASD usually turns over its schools to charter organizations, but you also chose to operate a handful of schools yourself in the Frayser community of Memphis. Some of those ASD schools have continued to struggle academically. What happened?

Last year we directly operated six schools in Frayser. Two did really well, two did moderately well, and two struggled. It was our second year of running schools on top of all of the other work we were responsible for in order to build and run a school district. I think for us, it goes back to the idea of accountability for results. All of us – ASD, charters and districts – should only be allowed to run schools if we do a good job. And while I believe we have made progress in all of the Frayser schools from the school culture standpoint, if you look at achievement, this year is going to be a real telling year for the first set of schools we opened that will complete their third year in the ASD. Research says that by the end of the third year, you should see gains in proficiency that show the school is on the right track. We know our students and staff are working hard, and we are cautiously optimistic about our end-of-year results.

What is your plan for these schools?

We are in the process of determining the long-term plan for these schools. One option is to convert them to a charter school network that will eventually return to Shelby County Schools. Another option is to transition them directly back to Shelby County Schools. All of our schools, regardless of type of school, will eventually go back to the local district. We will take the next 12 months to work with SCS to determine which option makes the most sense. So I think the question we have to answer is how do they go back? Do they go back as direct-run schools or as charter schools?

Last month, YES Prep pulled out of its agreement with the ASD to begin operating one school in South Memphis. That had to be a great disappointment to you, both professionally and personally. Now that you’ve had time to process YES Prep’s exit, what are your thoughts about why this happened, what it tells us about the charter landscape in Memphis, and what this means going forward as ASD continues its turnaround work?

I was shocked and disappointed in YES Prep’s decision. Like I have said before, not everyone is cut out to do the difficult work of turning around neighborhood schools. I believe Memphis has some of the best conditions in the country for educators to start and operate high-performing charter schools. There is a need; there is a great policy environment; the leadership across the city is focused on making our schools better; and there is a local philanthropic community invested in both Shelby County Schools and ASD priority schools. Most importantly, we have terrific and committed educators who are working in our ASD schools across Memphis.

Can you tell us about your level of commitment to the ASD and to the state of Tennessee now that you’re almost four years in?

I am as optimistic and committed as ever. I believe in the work we are doing. I am excited about the progress being made. I am committed to taking the lessons we have learned to make the ASD even better moving forward.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Each month, Chalkbeat conducts a Q&A interview with a different leader, innovator, influential thinker or hero across Tennessee’s education community. We invite readers to email Chalkbeat suggestions for future subjects to tn.tips@chalkbeat.org.