Advocates of a proposal to set ground rules between the Shelby County school board and Memphis-area charter schools are hoping the third try’s the charm.

A board committee is scheduled to collect public input about a proposed “charter compact” this week, six months after board members demanded greater community input in the plan and more than a year after the then-recently elected board tabled the proposal for the first time.

Now the group that the district convened to draft the compact has more community members on it, and board members say they have increasingly realized the value of clarifying the board’s role in Memphis’ charter sector.

The compact could resolve some growing points of tension between the district and the local charter sector: where charter schools get to open, how much they pay in rent, which students they serve, and what district services they can tap into, for example.

“When there’s a shared agreement and it’s in writing, then there’s no question around what’s happening,” said Miska Clay Bibbs, the board member who revived the proposal.

Growing recognition that common rules are necessary

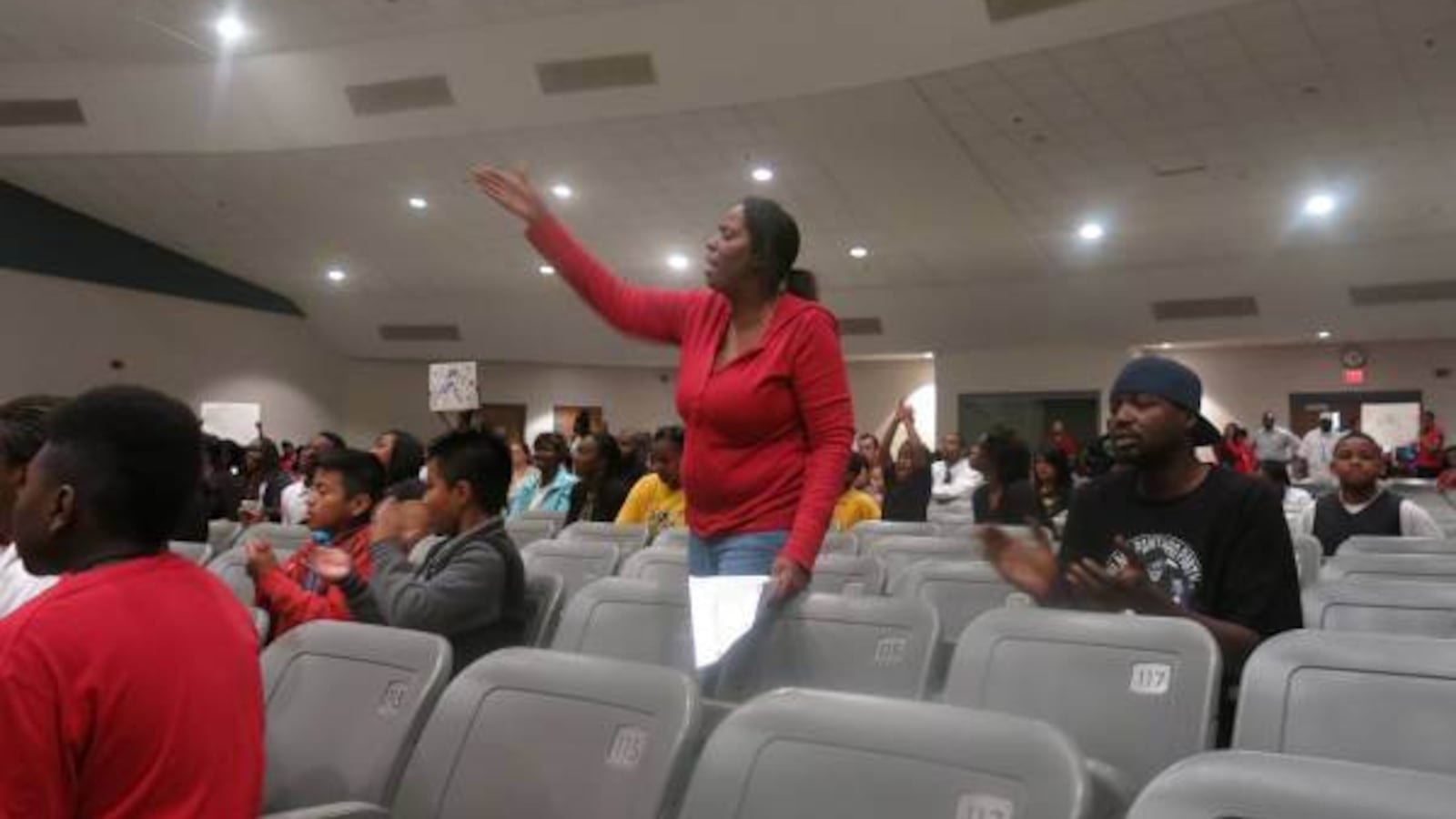

Bibbs reintroduced the compact proposal in July, a week after a contentious meeting that brimmed with issues related to charter schools — whether the board should shutter a financially shaky school, allow three operators to open new schools, and block an academically struggling operator from opening its third school.

The board is responsible for authorizing charter schools, which are publicly funded but privately managed and exempt from many regulations as long as they perform well. But exactly what kinds of oversight should take place after schools are open is less clear, and board members struggled to understand how the recommendations they faced had been made.

The two-hour discussion showed that district administrators need clearer guidelines for working with charter schools, said board member Mike Kernell.

“We sensed the ambiguity,” Kernell said. “The law may give us latitude [for overseeing charter schools], but I think we need to be stricter in our own procedures.”

A national strategy for easing conflict around charter schools

Clarifying what those procedures should be — and easing simmering tensions between the two sectors — was the goal in March 2014 when Shelby County Schools chief Dorsey Hopson convened a committee to draft a charter-district compact.

Hopson was following in the footsteps of more than 16 other school districts, including Nashville’s, that had signed charter compacts by 2013, according to the Center on Reinventing Public Education, a research and advocacy group tracking the issue.

Those compacts led to some concrete changes: The Nashville compact, signed in 2010, resulted in the creation of a state report card for parents that grades both charter and traditional schools and also pushed for charter operators to open schools in the city’s neediest neighborhoods.

But even more, the compacts signaled that districts had accepted charter schools as part of their educational landscape, and charter schools had acknowledged that they need to address the criticism that they play on an uneven field.

Many of those cities subsequently received millions of dollars in funds from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to support collaboration between district and charter schools. The foundation invested in districts with charter compacts to reward efforts to increase the number of high-performing schools, no matter who runs them.

That is something that Hopson has said he wants to do, expressing an attitude common among reform-oriented schools chiefs across the country. At the same time, every student who leaves a district school for a charter school depletes Hopson’s student population, workforce and budget. And he has echoed criticism of local charter schools that they do not follow the same rules as district schools, particularly when it comes to enrolling and disciplining high-needs students.

What the compact framework says and how it could change

The committee that Hopson appointed — made up of of five district administrators, a former district principal who has openly advocated for charter schools, three charter school administrators, and two administrators of local philanthropic foundations that fund charter schools — came to a series of agreements.

The district would guarantee “equitable funding” to charter schools and traditional public schools; provide charter schools “equal access” to district resources such as special education and maintenance services; and clarify the way it assesses all schools so that decisions to open or close charter schools can easily be explained.

In exchange, charter schools would adopt a number of district policies, most notably one governing the expulsion of students. They also would have to pay a percentage of their state funds to the district.

Both sectors would formally agree to encourage more academic and professional development collaboration between teachers and administrators.

It’s unlikely that the draft compact would be adopted without revisions. The provision that would allow charter schools to operate in district-owned buildings without paying rent, in particular, could prove difficult to get through the board. Reducing or eliminating rent payments could entice charter operators that are part of the state-run Achievement School District — which does not require its schools to pay rent — to expand under Shelby County Schools’ oversight. But at the same time, the board had to cut more than $125 million from Shelby County Schools’ 2015-16 budget, and the $1.2 million in annual revenue that the district currently collects from charter schools could be hard to give up.

Even Bibbs said she was hesitant to go as far as the March draft seems to allow.

“I don’t think anything should be free,” said Bibbs, who previously has worked for a local charter school. “I’m open to [hearing] how we can come to a middle of the road.”

Another significant issue could be the charter approval process, which isn’t addressed in the March compact draft. Several board members say clear guidelines are needed, especially after a 2014 state law allowed charter operators whose applications are rejected by their local school boards to get approval from the State Board of Education — something that Omni Prep is currently doing after Shelby County’s board denied its bid to open a third school.

In addition to setting up a potential scenario in which charter schools could operate in a district’s backyard without local oversight, the law means that having an inconsistent approval process could make Shelby County Schools vulnerable to lawsuit, Kernell said.

No panacea, but a starting point

The school board’s engagement committee will hear public input on Wednesday, and it has invited charter operators and others to weigh in. Then, the district-organized committee — which now includes community members from Frayser, a neighborhood with a growing number of charter schools — will incorporate the feedback into the draft compact before sending it back to the to the engagement committee, which will send it to the full board for approval. That could happen as early as next month.

If the board ultimately signs off on a compact, it probably will not ensure smooth relations between the district and local charter schools. Even with a compact in place, Nashville school board members regularly debate the costs and benefits of charter schools, and the board frequently is split about whether or how quickly to expand the charter sector. Similarly, a compact signed in 2010 in New York City did not prevent conflict around charter schools from taking center stage when a new mayor who was less favorable to them took over.

But Cardell Orrin, director of Stand For Children, a nonprofit group that has pushed for the compact in Memphis on behalf of the charter sector, said he hoped it would center debates on a shared purpose.

“I hope the compact improves the ability of charter schools to deliver quality education to students [and] holds them accountable for doing it, and the district sees the charters as a part of providing overall quality education,” he said.