The mother of nine children who have attended Memphis schools, Apryle Young-Lanier has witnessed a paradigm shift in the city’s education landscape, where the charter sector now consumes a fourth of the schools — and is growing.

Charter schools have offered her children a better education, she said, in a city that long neglected the deteriorating education of its black and poor students.

“They offer curriculum our children would otherwise not be exposed to,” she said, adding that charters have stepped in to help address neighborhood blight left by a trail of school closures. “The buildings were empty, not being used,” she said.

But that growth hasn’t come without pain, angst and outright anger in a city that also is home to one of the nation’s largest chapters of the NAACP, a leading group in the charge to stop charter expansion, as well as the state-run Achievement School District, which relies on charters for its school turnaround work.

The intersection puts Memphis at an interesting crossroads ahead of this weekend’s vote in Cincinnati by the NAACP’s national board to formalize its stance against charter school growth.

Memphis has become a battleground city in efforts to improve chronically low-performing schools, introducing charters as a tool for innovation beginning in 2003. Today, Shelby County Schools has 45 charters among its 186 schools, and the state-run district operates 28 charter schools as part of its turnaround model.

But their effectiveness, as well as the money they siphon off from traditional schools, remains a source of debate and sometimes outrage.

Last December, after a Vanderbilt University study said the Memphis district’s own school turnaround program has had more initial success than the state’s charter-reliant model, the school board for Shelby County Schools called for a moratorium on the ASD’s growth until it could show improvement. Soon after, the Memphis NAACP and black state legislators joined in the call.

“Our schools have been used as an educational experiment to test models of education theory,” NAACP leaders said in a statement, “while our students continue to struggle with the effects of years of debilitating poverty.”

At the same time, newly formed Memphis groups favoring school choice have steadily grown their ranks and heightened their voice in support of the ASD, charter schools, tuition vouchers and other changes they say can help put children of color on equal footing when it comes to getting a public education. Memphis is 63 percent black, and nearly 80 percent of the school system’s students live in poverty.

“Charter schools add much needed value to the fabric of our local educational landscape,” said Mendell Grinter, executive director of Campaign for School Equity, formerly a chapter of the Black Alliance for Educational Options, a national school choice group. “When given the option, parents increasingly are choosing to enroll their children in public charter schools and in many neighborhoods, the demand for charter schools is far outpacing the supply.”

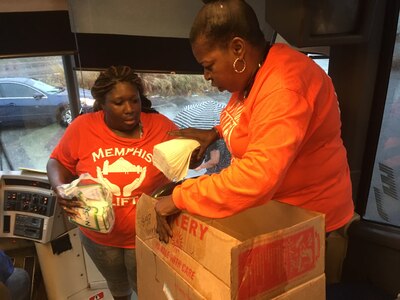

Memphis Lift is another organization that sprang up in 2015 to organize black parents wanting school choice. On Friday, the group dispatched about 150 parents from Memphis and Nashville to Cincinnati ahead of Saturday’s vote. Memphis Lift, which also advocated for more funding for traditional schools this year, has ties to the wife of the ASD’s founding superintendent, Chris Barbic.

“We just want the NAACP to know that this is not what we want,” said Sarah Carpenter, the group’s executive director. “We want a moratorium on low-performing schools, period, not just charter schools.”

The national board’s resolution instructs local chapters to advocate against preferential funding or tax breaks for charter schools and for increased transparency and oversight. It also denounces “disproportionately high use of punitive and exclusionary discipline” in charter schools, documented waste of public funds in some, and “increased segregation rather than diverse integration.”

Local NAACP leaders have kept a low profile in discussions over the resolution, the latest volley in decades of sparring by black leaders over the role of charter schools in public education.

Madeline Taylor, the chapter’s long-time executive director, declined to comment to Chalkbeat, and multiple calls to other leaders were not answered. Grinter and Carpenter’s efforts to engage the NAACP about charters have also been met with silence.

Three Memphians sit on the NAACP’s 63-member national board: Jesse H. Turner Jr., the organization’s treasurer and the president of Tri-State Bank of Memphis; Rabbi Micah Greenstein of Temple Israel of Memphis; and Bishop William Graves of Christian Methodist Episcopal Church.

Nationally, charter schools have a disproportionately higher black student population, and many black leaders in the charter sector have urged the NAACP to reject the resolution.

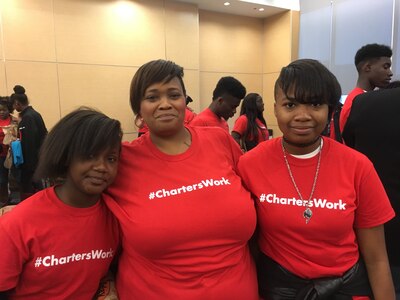

In Memphis on Friday, Young-Lanier was among about 65 students, parents and education advocates who rallied in favor of school choice during a morning rally at the National Civil Rights Museum, a monument to Memphis’ proud but painful history in the crusade for racial equality.

“I think they have this cookie-cutter image of charter schools,” she said later of local charter critics. “I can’t speak for other cities. But here in Memphis, they work really well.”

Many disagree with that statement, and Shelby County Schools is seeking to sort out the facts.

The district came out with its first annual charter school report over the summer, showing a mixed bag of performance as the district seeks to better manage the burgeoning group.