Cutting unnecessary suspensions in Memphis schools might start with a simple “good morning.”

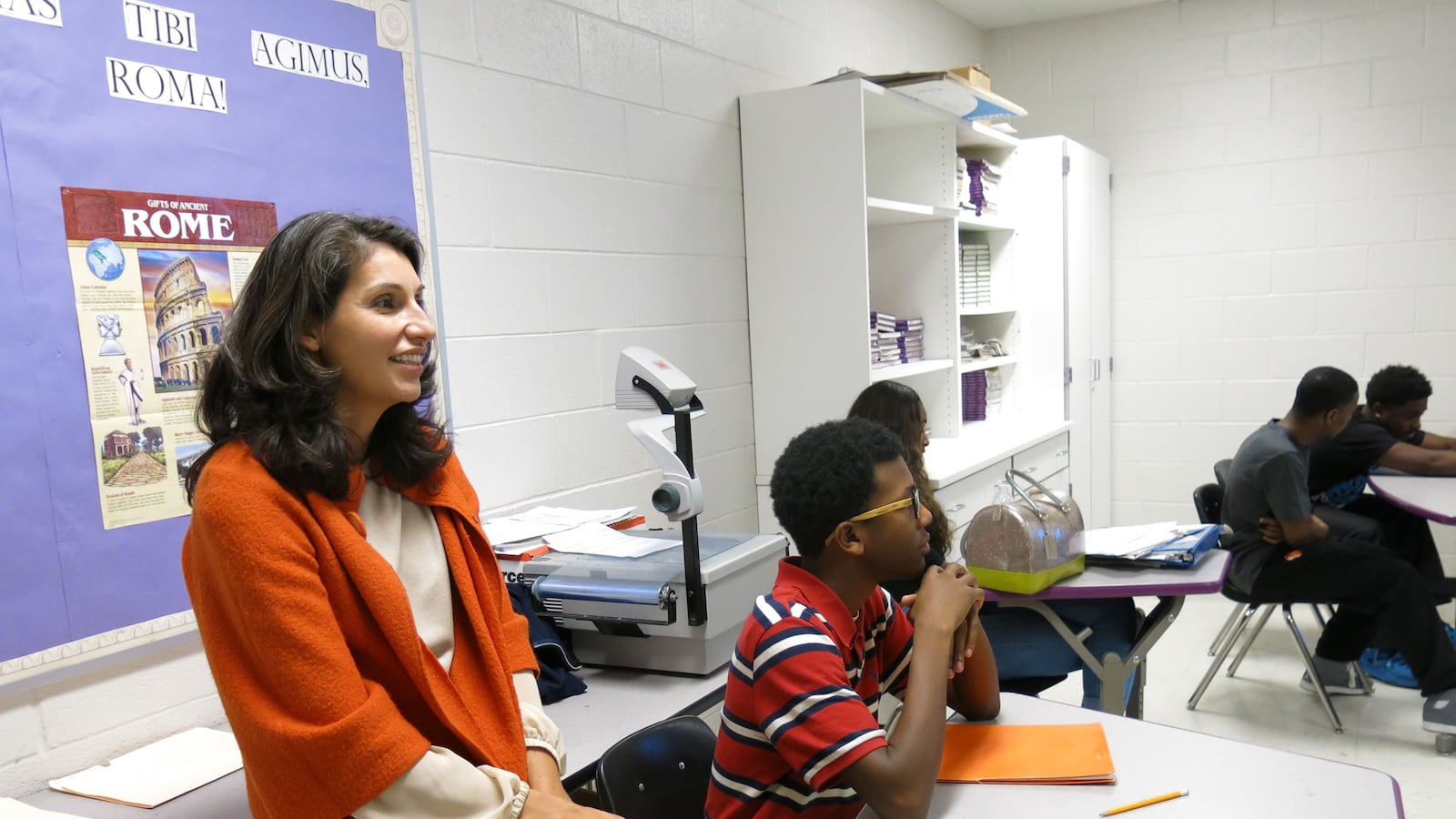

At least, that’s the hope of Heidi Ramirez, chief academic officer for Shelby County Schools.

Ramirez and her colleagues in Tennessee’s largest district are among the growing number of educators across the nation who have concluded that suspending students frequently comes at too high a cost. A recent decline in suspensions meant that local students spent a total of 65,000 more days in class last year than the year before, Ramirez said. But too many students are still losing valuable learning time and are getting alienated from school because of suspensions. (Read here about suspension trends in Memphis and across Tennessee.)

Some cities, including Miami and Indianapolis, have outright banned suspensions in most cases. Memphis hasn’t gone so far, but Ramirez said the district is working hard to change the tone it sets for students.

“A lot of our high schools have metal detectors, and we ask our students to go through those first thing,” she said. “The concern is that the first thing a child hears is ‘Pull up your pants.’ What if it was, ‘Good morning. Glad you’re here’?

“We’re really trying to shift the orientation from that of control to that of collaboration and positive culture.”

District leaders are monitoring discipline more closely than ever before, Ramirez said. Officials crunch the latest suspension data every month, investigating spikes and rewarding declines. They work closely with Gerald Darling, the district’s head of school security, who is on board with the basic direction. They’ve trained school leaders to recognize when students need extra emotional support because of challenges in their home lives. And they’ve encouraged principals to adopt alternatives to suspension, such as “restorative justice” programs that prioritize getting students to reflect on and change their behavior over simply punishing them.

Still, Ramirez says those efforts are battling scarcities of time, money and school personnel. Restorative practices are “not happening at the scale we’d like,” she said, suggesting that the district has a lot of work to do to dissuade educators from suspending students.

“Suspensions themselves are sort of the last-resort treatment,” Ramirez said. “For a lot of folks, out-of-school suspension was the primary tool in the box. So we’ve had to get smarter about helping them develop other tools.”

"For a lot of folks, out-of-school suspension was the primary tool in the box. So we’ve had to get smarter about helping them develop other tools."

Heidi Ramirez, chief academic officer

Shelby County could learn from Nashville, where suspensions — and the racial disparities in who receives them — are on the decline.

There, officials have made school-level changes, rather than district-level trainings that focus on the reasons students might be acting out.

“Students don’t necessarily misbehave because they have adverse childhood experiences,” said Tony Majors, a top leader in Metropolitan Nashville Public Schools. “Student behavior is often associated with the climate and culture in an individual school.”

Ramirez said the culture shift she wants to achieve in Memphis is possible — but not simple, given the systems that schools have had in place for years. When disruptive behavior occurs, school administrators often default to suspension and expulsion in an effort to keep their school safe.

“We are helping folks understand that you still have to keep schools safe,” she said, “but there’s a space in there where we can do that and our students can feel nurtured and our adults, as well.”