In 2009, a group of philanthropists and local educators set an ambitious goal: What if Memphis City Schools (now Shelby County Schools) could become a national model of great teaching for all children? Between the philanthropists — including up to $90 million from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation — and a federal grant soon after from the Obama administration, the district poured $184 million into addressing the district’s chronic failure in recruiting, developing and retaining talent for its schools and classrooms. Over the last six and a half years, many of the basic ways schools and teachers are supported have been completely overhauled. But student achievement still lags. And while some teachers have welcomed the changes, others feel more frustrated than before. This is the story of how a school system leveraged millions of dollars to shift from an environment of isolation and angst into a culture that seeks to support and value the people who work in its schools. And it’s about the students who are the guinea pigs for determining if rising teacher quality translates into higher student achievement.

Allison Graybeal sobbed in her car in the parking lot of the Memphis school where she taught. The trained economist had left a comfortable job at an accounting firm to become a teacher at one of Tennessee’s lowest performing middle schools. “I wanted to wake up in the mornings with a sense of purpose,” she explains.

But on most days in 2011, her first year of teaching at Raleigh Egypt Middle School, Graybeal’s eighth-grade math students were struggling at basic addition and nowhere near ready to tackle the pre-algebra concepts they were expected to master on the state achievement test. Sometimes, she struggled just to settle down her students enough to listen to her lesson. On other days, transitioning them to small group work, a method her principal had suggested, dissolved into raucous chatter.

In her car after school, she was overwhelmed with doubt and worry. “I’ve lost them,” she kept thinking.

In this urban district — where many of the 112,000 students hope to be the first generation in their family to attend college, and where school staff often spend their own money buying children winter coats, doing laundry and offering gift cards for chicken sandwiches so their students have no excuse to miss class — success in school “is make or break,” Graybeal says.

“When you teach in a place like Memphis, the stakes are high,” she says. “Education is the way you will lift most of these kids out of poverty. You have to succeed. You have to be able to help these students have a better life.”

Yet, as her meltdown testified, when it came to how to lift up her students, Graybeal was at a total loss. Like many teachers across Memphis, she had little access to those who could help her serve her students better. At the same time, the city was a textbook example of a phenomenon that national observers were beginning to call the “widget” problem: Teachers were treated as interchangeable parts, placed in classrooms and paid the same way, regardless of their skills and backgrounds.

In many places, efforts to change that dynamic had followed the same trajectory as so many planned education reforms: Big, bold initiatives were quickly derailed by budget crises, legal constraints, and pressure from interest groups, including unions. The difference for Graybeal and her counterparts in Memphis, not to mention the students they believed they were failing, was that none of those things would substantially stop their school district from executing on its vision.

"When you teach in a place like Memphis, the stakes are high. Education is the way you will lift most of these kids out of poverty. You have to succeed. You have to be able to help these students have a better life."

Allison Graybeal, teacher

The starting point was a $90 million commitment from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, its second-largest education gift in 2009. Local philanthropists and, later, the Obama administration added more funding to overhaul teaching, and changes to state law and local bureaucracy eased the way.

As the unprecedented investment nears its end more than six years later, Memphis’ experience has indeed become a national case study, with many bright spots, but also many challenges.

Between 2010 and now, the district has overhauled how it hires, places, evaluates and pays teachers. The changes appear to have translated into stronger student achievement — most dramatically at some long-struggling schools — while district leaders believe the new structures eventually will have the same effect system-wide.

At the same time, the transition has come with real challenges, including demoralization among some educators and a realization that not all principals were equipped to change their schools’ culture around teaching. And across the city, many students continue to struggle academically.

Now, facing a $72 million education budget shortfall next year, Memphis leaders are scrambling to figure out how to continue the teacher quality reforms it took so long to cultivate.

“What we have asked teachers to do over the last few years has been extraordinary,” Shelby County Schools Superintendent Dorsey Hopson recently told a group of community leaders. “And we are definitely starting to see some progress, so we’ve got to make sure the cuts don’t reach the classroom and undermine what we’ve been working on the last few years.”

As Graybeal worried in her car, officials in Memphis and funders in Seattle were already at work to make sure that no future teacher would have the same struggles she was experiencing.

Before she entered the system, Memphis City Schools offered little in the way of coaching or evaluation for its teachers. Professional training seminars to arm them with successful teaching techniques were sporadic. Few principals observed or advised whether teaching models being used in class were effective, and if not, how to change them. When evaluations did occur, every five years, the feedback was too little, too late. And the district did little to ensure that individual students had the teachers most able to help them.

To a growing faction in the education world, that reality was a clear explanation for Memphis students’ abysmal academic performance. Several recent studies had shaken conventional wisdom about why students don’t do well, concluding that teachers vary widely in how much their students learn — and that the variation comes from the teachers themselves, not how they were trained or who their students are.

One of the researchers who came to that conclusion, Harvard professor Thomas Kane, attracted the attention of Bill Gates, the Microsoft executive who was then ramping up his education giving. Gates recruited Kane to lead the Gates Foundation’s efforts to figure out how to help school districts identify quality teaching and replicate it.

(Chalkbeat receives support from the Gates Foundation and other foundations that supported this effort. Learn about our donors here.)

Kane’s search for willing partners in that work took him to Tennessee — which unlike most states already was calculating each teacher’s annual impact on student learning — and to Memphis specifically. There, a charismatic new superintendent, Kriner Cash, had begun criticizing the district’s human capital practices almost as soon as he was appointed in 2008.

In late 2009, Cash got the phone call from Bill and Melinda Gates: They were signing off on Memphis’ application to become a flagship district for teacher quality improvement efforts, and they would give $90 million over six years to make that happen. Among the four grant recipients, only Tampa’s Hillsborough County Schools would get a bigger boost.

Cash called the grant a “game changer” that would help the district build new ways to find, measure, coach and deploy strong teachers and principals. This wasn’t just about reforming schools, he told his staff. This was about reforming a city. More effective teachers would mean higher-performing students, who would turn into more productive citizens, a more talented workforce.

“We listened. We believed it,” said Tequilla Banks, a district research and evaluation expert who’d been studying teacher quality for the school system.

They were heady with possibility and dreams. But they were not naive. As part of the grant application process, Banks had just completed an exhaustive evaluation of the district, scrutinizing the quality of staff at schools, how it hired and deployed teachers and staff, and how it evaluated and supported them once they were there.

They started by looking at data they already had — ”value-added” ratings for thousands of teachers. The Gates Foundation and other advocates were pushing for widespread use of such models, which aim to measure a teacher’s impact on student learning but have been criticized as inaccurate and overly reliant on test scores. Tennessee had been an early adopter, calculating ratings for core subject teachers since 1993 but barring their use in personnel decisions.

What Banks found dismayed her and her colleagues. About 20 percent of Memphis’ core subject teachers had ratings that suggested they routinely helped their students achieve more than year’s worth of progress within a single school year. But many of those were concentrated in Memphis’ selective, middle class and historically higher-performing schools, while most of the schools with chronically low test scores and the most challenging students had no teachers who met that mark.

None.

“What that told us was the chance of a child getting a highly effective teacher was a lottery,” recalls Banks, now a vice president at TNTP, an advocacy group that lobbies for tougher teacher evaluations. “It was luck of the draw.”

The district’s own researchers found that the school system had a sluggish human resources department that did most of its work manually and lost its best teaching candidates in an application process that took an average of 110 days. The district also was recruiting from colleges of education in late spring and summer, too late to get the best hires who’d been scouted by January. Once teachers were hired, there was little effort to support and evaluate them.

"... The chance of a child getting a highly effective teacher was a lottery. It was luck of the draw."

Tequilla Banks, TNTP vice president

Through a Gates-funded experiment it called the Teacher Effectiveness Initiative, the district set out to overhaul its hiring and staffing practices in order to recruit and identify higher quality teacher applicants. It disavowed a history of pay by tenure and experience in favor of a system that relied on principal evaluations and growth in student learning based on state test scores. Inside of schools, it began training principals and teachers with strong track records of raising student achievement to coach their colleagues. The district also sought to embolden principals to make funding and staffing decisions in schools, allowing principals and teachers to decide for themselves where they could thrive and make the biggest difference.

Just as the teacher effectiveness work got underway, two remarkable things happened to change its course.

First, the teacher evaluation template in Memphis’ Gates grant application had gone from something the district warned would encounter strong resistance from local educators to a requirement under state law. The new law — which Tennessee’s governor at the time said was influenced by the vision proposed by Memphis officials — also required teachers’ ratings to be the basis of all personnel decisions, from tenure to dismissal.

The changes happened because Tennessee lawmakers, who wanted to bring home a new pot of federal funds, dramatically reshaped the state’s education laws to require annual teacher evaluations that included student test scores. The lawmakers were responding to the Obama administration’s 2010 Race to the Top competition, which was inspired by the same theories behind Memphis’ teacher quality push and announced days before local officials turned in their Gates application.

Race to the Top divvied up $4.35 billion to states that promised, among other things, to measure students’ growth over time and design policies to reward and retain top teachers. Tennessee became one of the first winners, receiving half a billion dollars, of which about $69 million would go straight to Memphis schools.

The sweetened pot was a boon to the district. But the policy changes were just as significant: Memphis would not need to win the local union’s support for changing evaluations, avoiding a negotiation process that would sideline evaluation overhauls in other places.

With evaluations out of the way, Memphis officials moved into the fall of 2010 focused on using a peer coaching model and a new tool for measuring effective classroom teaching to help teachers improve. It had even begun piloting the work in a handful of schools. Then came a shocker: In November, a school board member formally suggested resolving a funding crisis by giving up the city’s right to run schools.

The proposal, to merge Memphis City Schools with several suburban districts, seemed like a long shot. But the following March, voters approved the surrender by a more than 2-to-1 margin, though just 17 percent of eligible voters cast a ballot. The vote launched the nation’s largest school district consolidation — and an almost immediate effort by the suburban districts to plot an exit strategy. (Six of them took advantage of a new law, hastily passed in response to the merger, to secede from the shared system.)

"The state really created a difficult situation for us. Any sense of security teachers had in their jobs was just stripped."

Keith Williams, executive director, teachers union

The upheaval seemed to threaten the district’s teacher improvement work by distracting its leaders from their narrow policy agenda. Top school leaders worried aloud that Gates would pull out of Memphis, taking the programs its funding supported with it. The Teacher Effectiveness Initiative went into “maintenance mode,” according to Banks.

“It was tough to keep innovating and stay focused on continuous improvement when we were focused on ensuring that the work was sustained through the merger,” she said, adding that officials also worried about how to implement the new coaching and evaluation system across the rambling 150,000-student district the proposed merger would create.

But when local philanthropists affirmed their commitment to the district’s teacher quality work, the Gates Foundation kept its pledge intact through 2016.

And in the end, the shakeup and uncertainty that could have quashed the nascent Gates-funded reforms allowed them to take root. After the merger occurred in 2013 and suburban districts seceded in 2014, the new Shelby County Schools looked very similar in shape and student population to the Memphis City Schools district it replaced. But the district had been forced to rebuild its operations from scratch, making rewriting its way of business easier than it might otherwise have been.

A new school board and superintendent took charge in the wake of the merger, and they were not beholden to decades-old contracts and teachers union agreements. Meanwhile, the local teachers union — already struggling, with only about half of Memphis educators as members — had been weakened by two 2011 state laws that limited collective bargaining for public school teachers and made it harder for them to get and keep tenure. The laws paved the way for the district to use Gates funding to jumpstart the changes to salary and tenure practices that it had promised the foundation.

“The state really created a difficult situation for us,” said Keith Williams, executive director for the teachers union in Memphis and Shelby County. “[The state’s new laws] made it almost impossible to earn or keep tenure, and then it limited collective bargaining to the point that we couldn’t even have a contract. Any sense of security teachers had in their jobs was just stripped. It was a double whammy.”

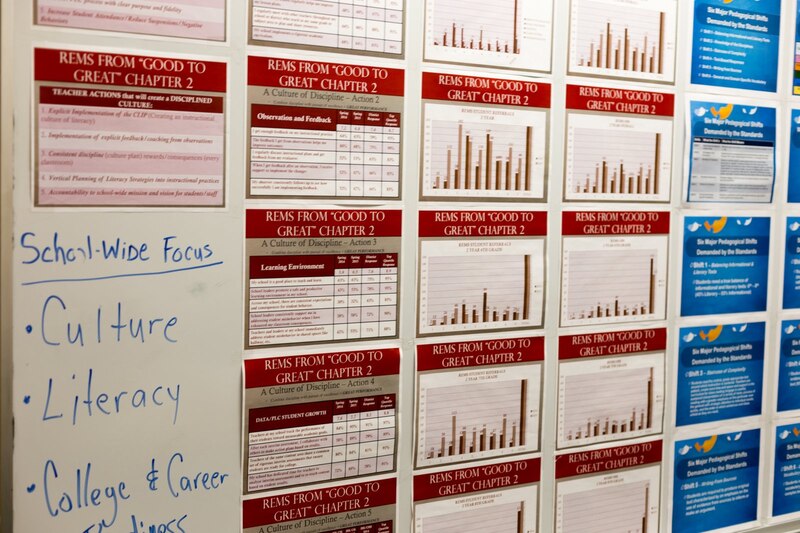

With some of its hardest-to-fulfill promises made possible by changes to state law, the newly created Shelby County Schools forged ahead with the Teacher Effectiveness Initiative. In the three years that followed, the district would spend more than $3.5 million to develop a rubric to grade teachers’ performance and train district staff on how to use it. It deployed more than 400 full-time and part-time coaches with iPads to schools to document teacher performance in Shelby County classrooms.

And nearly 2,000 teachers — including Allison Graybeal — received coaching and targeted feedback to make them more effective in the classroom.

When Graybeal left Raleigh Egypt Middle and joined the faculty of Middle College High in the fall of 2012, principal Docia Generette-Walker had barely been there six months. But the new principal already was redefining the way the midtown Memphis school operated.

The high school of 280 students was literally and figuratively breaking down. While the school screens its students and had long outperformed other schools in Memphis, many of its students struggled in middle school and most came from homes in the city’s poorest neighborhoods. A number of key teachers and a principal left unexpectedly in the middle of 2011, and students were learning out of classrooms in trailers while the school’s aging building was being renovated.

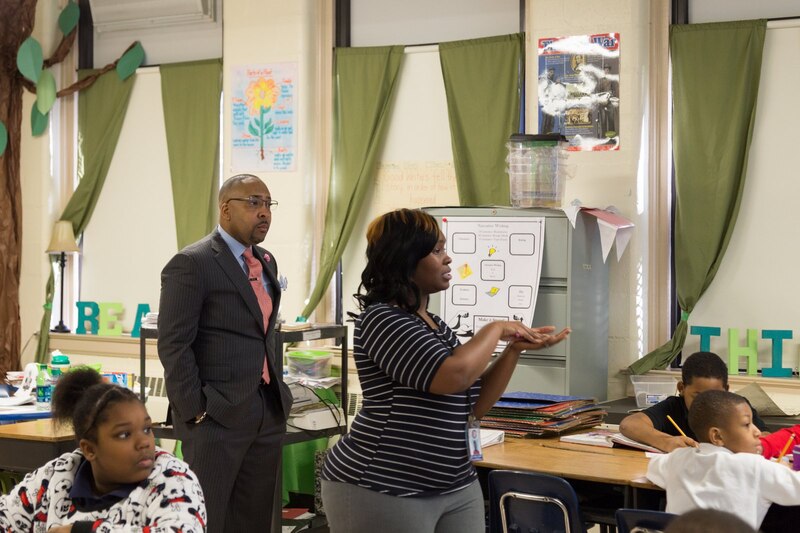

Generette-Walker capitalized on that disarray to transform the way the school operated, introducing a system of teacher leaders and coaches. “We had some great teachers doing great things in their classroom. The attitude was ‘My kids are doing fine,’” Generette-Walker recalls. But that wasn’t good enough. “How can we take the best teachers and spread them out so they can influence all of the students?” she pressed her staff.

Emboldened by the Gates-funded teacher support work, the principal began conducting weekly observations in every classroom, where she and assistant principal Andy Demster videotaped and recorded teaching practices and lesson planning sessions. They called it “reflective practice” and offered specific feedback on how to make lessons more relevant, use small group instruction more effectively, and redirect misbehavior. They braced prospective teachers that coming to Middle College High meant “getting used to someone being in your room, watching you, once maybe more a week.”

"How can we take the best teachers and spread them out so they can influence all of the students?"

Docia Generette-Walker, principal

As a fledgling teacher, Graybeal had struggled to be nimble and responsive in the “juggling act” that teaching requires.

First, there’s what to teach, preferably written on the board as a clear objective that every student can understand. Then, how to teach it: Which is the best way to get the content across? Straight teacher-led lecture? Small group work? Large class discussion? Then there’s the psychology of teaching: how to curb misbehavior before it erupts, how to gauge the underlying cause of the student’s outburst and redirect. And last, how to “read” student feedback: Can you tell who is understanding what you’re saying? Can you tell who isn’t? If students aren’t getting the content, what can you change about how you teach — right then and there — to make sure they are understanding?

Demster suggested that Graybeal employ a mix of teacher-led lectures, small group work, and individual work, using timers for pacing to keep the class fresh and students engaged. He suggested she give the students individual whiteboards to write quick responses to her questions to hold up so she would know exactly who is understanding the lesson and who isn’t. She also dropped her shy, soft-spoken voice an octave to a firm bass that would quickly get her students’ attention.

By 2014, after two years of coaching, Graybeal had improved her teaching methods so much that she was a coach herself to three of her peers. Her school also was benefiting from the coaching model. Over the last four years, student proficiency has climbed more than 20 percentage points on state tests in algebra and English. Last year, Middle College High was one of six in Tennessee to win national honors for both performance and improvement.

More importantly, Generette-Walker said, teachers’ mindsets have changed fundamentally. “If you needed a coach, it used to have a negative connotation,” she said. “Now, the teachers are getting used to having someone observing them every week. It’s a break in the isolation. We all need that support.”

What happened at Middle College High was a best-case scenario for what Gates and district officials hoped would transpire to improve teaching at individual schools. Inside district headquarters, leaders were working to make it more likely for that scenario to repeat across the district.

But they soon saw that changing the status quo wouldn’t be easy everywhere. They rolled out the rubric for effective teaching that they had hired a California consulting firm, Insight Education Group, to produce. That rubric included bullet points on everything from how to transition between lessons to how to leverage technology or methods like creative role-playing to cement difficult concepts.

It also made teachers nervous. They would have to demonstrate mastery of dozens of skills just to meet the district’s expectations. To exceed expectations — and be eligible for potential bonuses and positions of responsibility — they would have to do even better.

Checking all of the boxes can impede doing what it takes to reach students, some teachers say. “Sometimes you have to put on your dog and pony show,” said Laura Wilons, a teacher at Grahamwood Elementary School.

A big focus of the district’s rollout became managing teachers’ fears that the rubric would be a punitive measure designed to hurt, rather than help. Those fears deepened as the school system shakeup pushed the local teachers union to the sidelines.

“Early on, the teachers were involved in the discussions,” said the union’s leader, Williams. “We sat on the committees and helped shape the rubric. But as we moved on, we lost control and it turned into an autocratic ‘I gotcha’ system.”

That characterization isn’t accurate, Superintendent Hopson said, but it is widespread.

“When I talk to teachers across the district about the evaluation system, what I keep hearing is the angst,” Hopson said. “That’s a cultural battle we are fighting on some level — this feeling that when you get your evaluation, when a principal comes into your class, watches you, offers feedback, it’s not a ‘gotcha.’ It’s there to help you grow, help you get better.”

In many ways, criticism of local changes followed a pattern playing out in cities across the nation. While union leaders initially were open to tying teachers’ ratings to student performance, their tolerance diminished as the stakes increased, complaints about the ratings’ fairness mounted, and specifics of the evaluation systems came under fire. Critiques of value-added models gained steam, and even the architect of Tennessee’s version said the state was using value-added scores inappropriately. The influence of powerful outside actors like the Gates Foundation increasingly came under attack.

"When I talk to teachers across the district about the evaluation system, what I keep hearing is the angst. That’s a cultural battle we are fighting on some level."

Superintendent Dorsey Hopson

Despite the growing pushback, Memphis officials plowed ahead in using the rubric to identify, hire, and support teacher and principal candidates. The Gates money also helped support roughly $3 million in existing teacher recruitment contracts with Teach For America, New Leaders for New Schools and The New Teacher Project — costs that the district previously had shouldered alone.

The New Teacher Project, now known as TNTP, also helped the school system revamp its hiring by creating a more organized, computerized system to post and fill vacancies and track prospective teacher hires. The district had been mired in paperwork. To post a vacancy, the personnel department circulated forms that required no fewer than six signatures from various departments. Forms languished on desks, while prospective hires were asked to provide official college transcripts, a weeks-long process that caused many to drop out.

TNTP cut out most of those steps while computerizing others and made the application process more rigorous and efficient. It also introduced an ideological litmus test for potential teachers: Candidates who said they believed that all students can learn and that teachers have the greatest influence on student performance were allowed in. Applicants who answered that some students’ life circumstances would dictate their performance were turned away.

In the end, a district that previously had only screened for college GPA and licensure now was screening for applicants who bought into the district’s vision for its future.

The changes extended to the way teachers landed in individual schools. Overall, new teachers were brought on board within a week, instead of the more than three months it used to take. As significantly, the district adopted the practice of “mutual consent,” in which teachers and principals agree to work together rather than teachers being placed into vacancies by seniority. The practice, which several other major districts adopted at the same time, set the stage for teachers’ ratings to decide who would be laid off when schools closed.

It also meant that principals were now choosing the teachers that they were increasingly being tasked with improving. The district would spend $74 million on teacher coaches and training courses that benefited Graybeal, and another $27 million on training for principals like Generette-Walker.

Did it work? For teachers like Allison Graybeal, the answer is absolutely.

Graybeal said coaching has helped her with the nuts and bolts of classroom instruction. Her principal and assistant principal have taught her to anticipate and address the hundreds of seemingly small decisions that can threaten to ruin hours of lesson planning, she says, like how students enter the room and sit down and how instructions are worded.

“I can’t just say, ‘OK, guys, let’s take out a piece of paper and try these problems,’” she said in the sing-songy voice she said she has discarded. “I have to transition into it.” Now, she is firm and clear: “OK, in the next five seconds, I want you to take out a piece of paper and work out the problems on the board. We will discuss your answers in two minutes.”

Graybeal is not alone. She was in a cohort of 1,900 teachers — out of about 7,000 across the district — to receive intensive coaching starting in 2012. A 2014 survey of 1,750 teachers found that two-thirds of teachers said they were more effective because of their coaches.

On the other end of the city, in North Memphis, veteran teacher Sherry Simmons was in that same group. Simmons said she’s getting the kind of support she wished for when she began teaching in the district in 1979. An English teacher at Raleigh Egypt High School, Simmons said her principal, Bo Griffin, visits her several times a week, offering suggestions on how to improve lessons. Recently, she said, he noticed that she was asking students to recall too many “whats” from their reading and encouraged her to challenge students to explain “the why” instead. On some days, he just leans back against a wall watching, offering moral support.

“I feel supported,” Simmons says. “The way he talks to you, it’s personal; he treats you with honor and respect and you never feel like he’s telling you you’re doing it wrong. He’s just trying to help and make it better.”

The impact of the teacher and principal coaching work has been greatest in the 18 schools that are part of the Innovation Zone, the district’s school turnaround program. Over the last three years, the district has used $1,000 signing and retention bonuses, along with promises of working for charismatic principals and receiving additional support, to lure 334 of the school system’s top-rated teachers and promising recruits to historically low-performing schools in the iZone. That influx is one explanation the district offers for iZone schools’ rapid test score gains, which outpace the increases in the state’s own turnaround initiative in Memphis.

Fifth-grade teacher Renata McNeil was one of the teachers who made the switch. She earned the top evaluation score at a high-performing, selective elementary school but chose to move to the iZone’s Cherokee Elementary, where 10 percent of students were proficient in reading and 14 percent were proficient in math in 2010. McNeil wanted to work with principal Rodney Rowan, under whose leadership test scores have risen sharply. Now, a third of students are proficient in English and two-thirds meet the state’s proficiency bar in math.

“I hire attitude and train skill,” says Rowan, who calls his work “intentional, collaborative and urgent” — or ICU, just like the trauma hospital five miles from his school. Here, within these cinder block walls, Rowan is saving lives too, he says.

But the district hasn’t been as successful with its Gates-funded work in the majority of its schools, where student test scores have been stagnant and the concentration of high-rated teachers is lower.

The district told the Gates Foundation that it would seek to fire low-rated teachers who did not improve. Indeed, it has dismissed 100 low-rated teachers a year, but another 800 still work in Memphis classrooms. About 100 of them have had multiple years of low ratings and multiple years of coaching, but their principals have not taken steps to remove them — consistent with research showing that principals tend to keep ineffective teachers in place to avoid the unpleasant and time-consuming work of firing them, even when they technically can.

Increasingly, district leaders have learned that principals are the linchpin of its effort to improve teacher quality.

The evaluation system that has become the heart of the effort gets the strongest marks in schools like Cherokee Elementary where teachers and principals work well together — a finding that confirms reams of other research about the significance of school leadership.

But in schools where the principals’ work and attitude with teachers and parents is tense or distant, teachers consider the evaluations arbitrary and subjective at best, punitive and capricious at worst.

One middle school teacher said her evaluations earn her high marks but are dotted with examples of “nit-picking.” For example, on one evaluation, the teacher lost points for failing to explicitly spell out the day’s learning objective on the board.

“It feels like a joke,” said the teacher, who like many other teachers interviewed for this story asked to remain anonymous for fear of retribution. “Here I am pushing these kids to intelligently discuss the environment in small groups, these kids, some of them barely came to me reading, and what the principal sees is that I didn’t state the objective.”

District leaders say they know they need to do more to help principals galvanize and support their teachers the way that Rowan does at Cherokee Elementary. They’ve started by renaming the Teacher Effectiveness Initiative — it’s now “Teacher and Leader Effectiveness.”

“We talk a lot about how teachers are the single greatest factor in schools to affect student achievement. What’s the second? It’s leadership,” said Heidi Ramirez, the district’s chief academic officer since 2015. “That’s our next biggest investment. We have a huge distance to go on that front.”

In its proposal to the Gates Foundation, Memphis school leaders acknowledged that none of the work is worth it unless students do better.

By this time, the district had forecast that local high schools would graduate 75 percent of their seniors but also that the students would perform well enough on national standardized tests to succeed in college. It also said least 60 percent of elementary and middle schoolers would be proficient in reading, math and science.

That hasn’t happened: Elementary and middle school students average in the 30th and 40th percentile on state tests. And while the fluctuating graduation rate landed last year exactly at 75 percent, up from 67 percent in 2008, most high schoolers do not score high enough on standardized tests to suggest they’re ready for college.

“Change of this magnitude is challenging and takes time,” said Josh Edelman, a Gates Foundation executive charged with keeping track of Memphis’ progress under the grant. “Too many students are still not prepared for post-secondary success.”

Hopson acknowledges the room for growth but says the gains at low-performing schools have been real.

“This is hard work,” said Hopson, who now also faces a budget crunch to continue the work as the Gates money dries up. “We missed the mark in some places, but those were ambitious goals set by the previous administrations, and I don’t think we should minimize the improvements we have made.”

Hopson’s assessment — that the investment kicked off real changes that the district should continue — is especially notable because the district that received the most money from the Gates Foundation is in the process of dismantling its teacher quality reforms. Facing a budget shortfall and resistance from its teachers union, Hillsborough County Schools in Florida fired the superintendent who ushered in the changes.

The school Graybeal left illustrates that even as Memphis has escaped some harsh realities of urban education reform, it is hardly immune to the pressures that can impede broad improvements. Progress is piecemeal — and sometimes comes too late.

In 2013-14, students at Raleigh Egypt Middle scored low on state tests, with only 13 percent reading on grade level and 14 percent proficient in math. That improved last year under a dynamic new principal who pushed intensive coaching for struggling teachers and tutoring for students. Math proficiency increased by 8 percentage points to 22 percent. Still, the gains were not enough to ward off takeover by the state-run Achievement School District, another vehicle for improvement created under Tennessee’s Race to the Top plan. Raleigh Egypt will convert to a charter school this fall.

Sometimes, Graybeal thinks of her former students. They should be ready to graduate from high school by now. Did they ever get better at algebra? Did they find a teacher who had learned as much as she had? She would be different — stronger, more confident — with those students today.

“Teaching can be so much of learning as you go, learning on your feet,” Graybeal reflects. “When you finally have the right support and help, to get that outside perspective is invaluable. It has made me the teacher I am today.”

Corrections & clarifications: March 21, 2016: A previous version of this story incorrectly stated the duration of the grant from the Gates Foundation. It also incorrectly said that the district’s evaluation system includes a peer mentor component; it does not, although Memphis does have a peer coaching system. It also incorrectly characterized the average performance of elementary and middle school students on state tests. The story has also been clarified to reflect that Tequilla Banks worked for the school district when she studied its teacher development practices and that scores for schools across Shelby County have risen in recent years, even as scores in Innovation Zone schools have risen fastest.