For more than two years, a funding lawsuit by Memphis school leaders has been winding through the state’s legal system.

Now, as the litigation inches closer to a court date next year, Shelby County Schools has gained a powerful ally in its battle with Tennessee over the adequacy of funding for its schools and students.

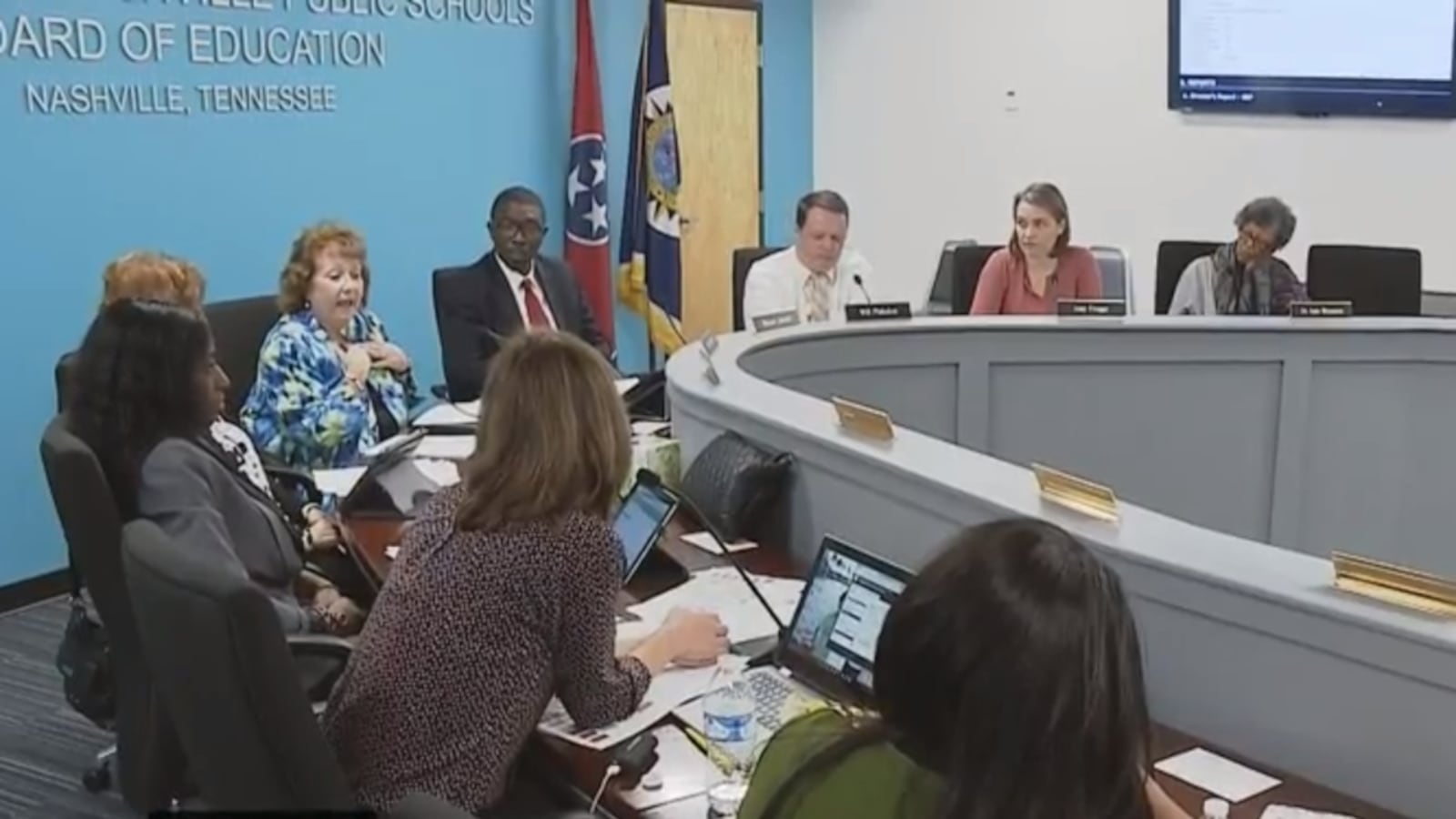

The board for Metropolitan Nashville Public Schools voted unanimously Tuesday to become a co-plaintiff in the case.

The decision ends almost three years of talk from Nashville about going to court.

In 2015 at the urging of then-director Jesse Register, the district’s board opted for conversation over litigation with Gov. Bill Haslam’s administration about how to improve education funding in Tennessee.

But Register moved on, and the board’s dissatisfaction grew as the percentage of state funding for the district’s budget shrank. Adding to their frustration, Haslam backed off last year from an enhanced funding formula approved in 2007 during the administration of his predecessor, Phil Bredesen.

“We’ve just come to grips with the harsh reality that we are a chronically underfunded school system,” said Will Pinkston, a board member who has urged legal action.

Nashville’s decision is welcome news for Memphis. A statement Wednesday from the state’s largest district called the lawsuit “the most important civil rights litigation in Tennessee in the last 30 years.”

“When you have the two largest school districts in Tennessee on the same side, I think it’s very powerful,” added former board chairman Chris Caldwell, who has championed the lawsuit in behalf of Shelby County Schools.

Both boards are working with Tennessee-based Baker Donelson, one of the South’s largest and oldest law firms. It has offices in both cities.

“We believe that our original case had a strong message about the inadequacy of education funding in Tennessee,” said Lori Patterson, lead attorney in the case from Memphis. “We believe that having the second largest district in the state join the suit and make the same claims only makes the message stronger.”

Haslam’s administration declined to comment Wednesday about the new development, but has stood by Tennessee’s funding model. In a 2016 response to the Shelby County lawsuit, the state said its formula known as the Basic Education Plan, or BEP, provides adequate funding under state law.

But Shelby County, in its 2015 suit, argues that not only does the state not adequately fund K-12 schools, it doesn’t fully fund its own formula. And the formula, it charges, “fails to take into account the actual costs of funding an education,” especially for the many poor students in Memphis. To provide an adequate education, the lawsuit says the district needs more resources to pay for everything from math and reading tutors to guidance counselors and social workers.

States often get sued over funding for schools — and frequently lose those cases. In Tennessee, state courts heard three such cases from the late 1980s to the early 2000s, siding with local districts every time. Those suits keyed in on built-in inequities in the state’s funding formula that cause some districts to get more money than others.

This time, the argument is about adequacy. What is the true cost of educating today’s students, especially in the shift to more rigorous academic standards?

Tennessee is also the defendant in a separate funding lawsuit filed in 2015 by seven southeast Tennessee school districts including Hamilton County Schools in Chattanooga.

Pinkston said Nashville opted to join the Memphis suit because its arguments are most applicable to the state’s second largest district. “Our student populations are very similar in terms of high socioeconomic needs,” he said.