Education Commissioner Candice McQueen says Tennessee’s turnaround district can do better, more efficient work under a lean structure that encourages more teamwork among its charter and direct-run schools.

That means providing mostly the same services with half as many positions as the Achievement School District tightens its belt for the long haul.

Effective July 1, only Superintendent Malika Anderson will retain her job while the state consolidates the offices of the ASD and its Achievement Schools in Memphis. Fifty-nine positions will be impacted, and current employees are being invited to reapply for 30 jobs under the new structure unveiled last week.

The new hierarchy represents the most dramatic round of cuts since the ASD began taking over chronically low-performing schools in 2012. The cuts continue a shrinkage that began last year when the State Department of Education started absorbing some ASD operational positions after an audit revealed incidents of financial mismanagement.

The change comes as the department seeks financial stability for its most rigorous school improvement tool.

The Achievement School District was created and developed with federal Race to the Top money but has been relying on philanthropic funding since the award ran out in 2015.

McQueen doesn’t want essential academic work dependent upon the whim of grant cycles. By streamlining the ASD’s structure, she said, the district will save $3 million annually and become solvent for the future.

“To be set up well from a financial perspective to do this work in a dynamic environment is absolutely the right work for us to do now as we go forward, even more aggressively around school improvement,” McQueen told Chalkbeat this week.

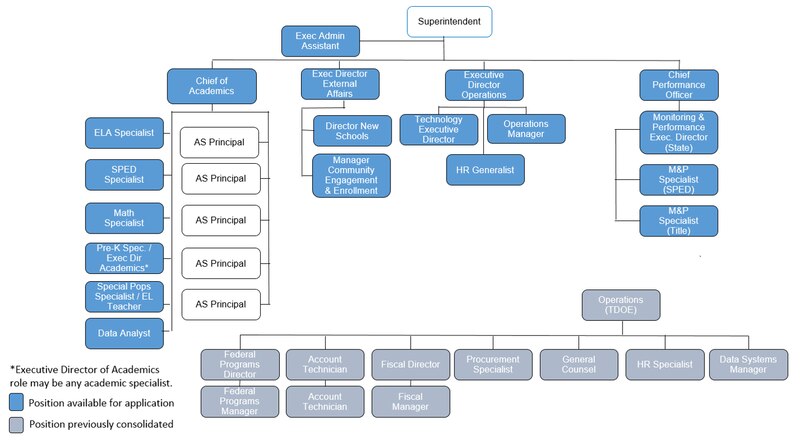

Four chiefs will report to Anderson under a structure that in some ways looks more like a traditional school district.

For the first time, the ASD will have a chief academic officer, a key position for most school systems. That person will oversee principals at each of the five schools that make up Achievement Schools, an ASD-run network in the Frayser community of Memphis. The job also will entail oversight of six academic specialists, who will work primarily with Achievement Schools, but also look for opportunities to share practices across the district’s 26 charter schools.

“This chief academic officer will be looking at what we learn across the (district) and how we can learn as a network and continue to grow,” McQueen said.

The other three lieutenants will include an executive director of external affairs, who will be charged with community relations; an executive director of operations, who will work closely with the State Department of Education on matters around accounting and human resources; and a chief performance officer, who will evaluate the district’s schools and recruit charter operators interested in turnaround work.

McQueen called the chief performance officer’s role “critical” to the process of recruiting and authorizing high-quality charter networks — and then monitoring their work.

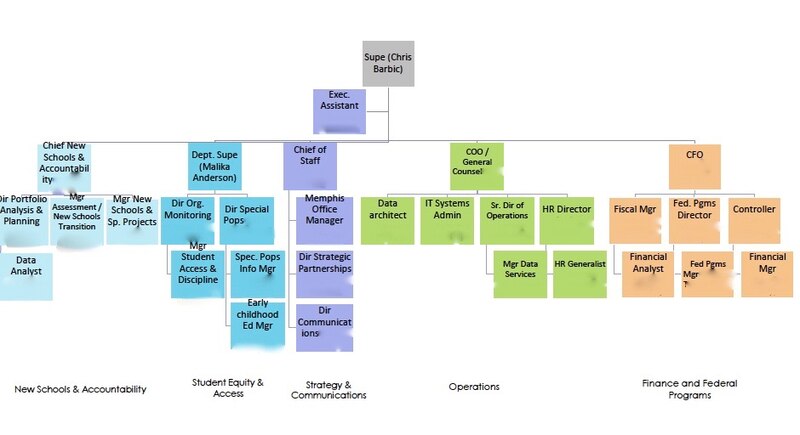

The hierarchy is simplified somewhat from 2015 before founding Superintendent Chris Barbic left — and after the Achievement Schools had broken off to create its own central office.

At the time, ASD leaders expected to become financially sustainable under a new $200-per-pupil fee charged to its charter operators. However, those fees have generated less revenue than projected due to declining enrollment at some of its charter schools.

Beginning this July, the ASD is changing its fee structure so that charter operators pay 2.5 percent of the state funding they receive for their students.

Charter operators reached by Chalkbeat said they don’t expect the leaner structure to significantly impact their work.

“It just didn’t send shockwaves through our office,” said Jocquell Rodgers, spokeswoman for Green Dot Public Schools Tennessee. “I just don’t see where the cuts … will affect us negatively other than the higher fee.”

Bob Nardo, who heads Libertas School of Memphis, said the job cuts are not a reflection of the ASD’s performance, but rather the need to regroup based on enrollment and funding.

“It’s important to keep in mind what the ASD is going through right now is essentially what Shelby County Schools has gone through in recent years,” he said. “They need just enough to do their core task, which is hold us accountable to be thoughtful and strategic to transform priority schools, and I think they have enough to do that.”

Bobby White, CEO of Frayser Community Schools, said charter operators are more self-sufficient than when they joined the ASD’s portfolio of schools.

“Now that we have three, four years under our belt, I’m confident that we’ll be able to handle those supports…,” White said.

Laura Faith Kebede and Caroline Bauman contributed to this report.