A decade before grabbing national headlines for a tragic bus crash that killed six of its students last fall, Woodmore Elementary was the rare good-news story, a heralded example of successful school turnaround work.

Along with eight other struggling Chattanooga schools, Woodmore was chosen in 2001 as a laboratory for reforms aimed at improving student literacy. Through an initiative funded mostly by a local corporation, innovations included developing teacher-leaders, hiring instructional coaches, creating space for collaboration, and giving principals autonomy over everything from spending to professional development.

For a while, the reforms seemed to be working. Third-grade reading proficiency climbed from 50 to 75 percent by 2005, drawing the attention of then-U.S. Secretary of Education Margaret Spellings and garnering profiles in national publications like The Washington Post and Education Week.

But eventually, the initiative’s money ran out, and the schools backslid. When the state released its first list of lowest-performing “priority schools” in 2012, Woodmore and four other neighborhood schools from the so-called Benwood Initiative were on it. Today, they still rank in Tennessee’s bottom 5 percent, even as federal funding for them increased.

Those five Chattanooga schools exemplify both the promise and challenge of turnaround work — what can happen when the right ideas and resources are in place, but also how quickly improvements can dissipate without sustained focus and support.

The schools now are the focus of state officials who are weary of promises of locally driven improvements, even as a new superintendent with new ideas has arrived on the scene in Tennessee’s fourth largest city. Their future, as well as the future of about 2,300 students, will be decided this fall as state officials prepare to step in with a new turnaround plan, albeit one that they hope will be endorsed and supported by the community.

Tennessee Education Commissioner Candice McQueen says the five schools — Woodmore, Orchard Knob Elementary, Orchard Knob Middle, Dalewood Middle and Brainerd High — are in need of urgent interventions.

“Hamilton County has struggled to turn around these five low-performing priority schools, although most of them have been on the district’s radar for at least 15 years,” McQueen said recently. “That means a student at Woodmore Elementary in 2002 could have just graduated from Brainerd High and spent his or her entire K-12 education in schools that have not put them on the track for success.”

Struggling schools in a battered district

Tucked in Tennessee’s southeastern corner, Hamilton County’s school system has been battered in recent years by a relentless tempest. The fallout from a rape involving members of a high school basketball team contributed to the abrupt resignation of Superintendent Rick Smith in early 2016. Woodmore’s fatal crash occurred later in the year when a speeding school bus careened out of control with 37 students aboard, just before Thanksgiving. This year, the district is being challenged by the possible secession of three schools in Signal Mountain, a mostly white and affluent suburb that would take critical funding with it.

All the while, Hamilton County has grappled with underfunding, low test scores, a large percentage of impoverished students, and stark racial and economic segregation.

Community and civic leaders have joined forces in the last year to seek to turn the trajectory of the city’s public schools, initially under the interim leadership of Kirk Kelly and now under a new superintendent, Bryan Johnson.

“Our philosophy was that our kids could not afford for us to wait,” said chief academic officer Jill Levine of the most recent local improvement effort. “Whether we’re in place for a year or five years, we need to start right away.”

Not surprisingly, they turned to some of the strategies that proved successful under the Benwood Initiative.

Turnaround pioneer

The unique initiative kicked off in 2001 in the early days of No Child Left Behind, when the words “school turnaround” first crept into the American vernacular.

Tennessee had just released a statewide list of its lowest-performing schools compiled by an independent researcher, a precursor to its current list of “priority schools” in the state’s bottom 5 percent. The community was horrified that nine of the 20 bottom-scoring schools were in Chattanooga — and serving mostly poor and minority students. In response, the Benwood Foundation, created by the estate of a former president of the Coca-Cola Bottling Co., donated $5 million in a unique alliance with the school district and Chattanooga’s Public Education Foundation, which kicked in another $2.5 million.

Jesse Register was the superintendent at the time of the Hamilton County Department of Education. The future director of Metropolitan Nashville Public Schools, he oversaw a targeted plan to improve instruction at the Benwood schools. In a model similar to Tennessee’s innovation zones of today, all teachers were required to reapply for their jobs in an effort to weed out the least-committed ones. Then-Mayor Bob Corker, a future U.S. senator, created incentives to attract educators, including tuition-free graduate school and mortgage loans and the potential for raises of up to $5,000 if student test scores went up.

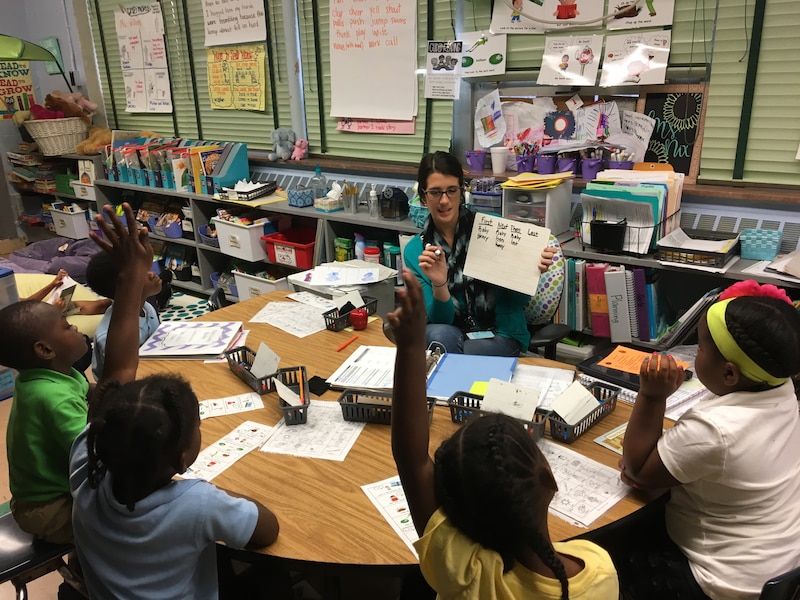

Nearly two-thirds of the original teachers were hired back, suggesting that the quality of the teacher workforce was never the problem. They just needed support, like on-the-job coaching, peer collaboration, and more time and help in the classroom. Researchers think Register’s next move was the biggest key to improvement. He greatly increased the number of support staff like instructional coaches.

The goal of the Benwood Initiative was to get all third-graders reading at or above grade-level by 2007. That didn’t happen, but the work was successful enough after five years to launch similar changes at eight more schools.

“The important thing we learned is that turnaround can be done,” said Dan Challener, longtime leader of the Public Education Fund.

But by the time the next $7 million grant ran out in 2012, Tennessee’s public education system looked markedly different than in 2001. The state had switched academic standards twice and was using a more rigorous test to measure student progress. Without a reinfusion of cash and commitment, improvements under the Benwood Initiative fizzled.

Old and new ideas

When Hamilton County leaders set to work reviving their district after Smith’s departure, they drew on several Benwood strategies like supporting teachers through coaching and adding support staff.

They also used federal and philanthropic funding to create literacy labs where teachers could get instruction and feedback, matched new teachers with mentors across the district, and created a “teacher think tank” to drive the district’s professional development programs.

“The idea is that if teachers see good models of teaching, it will improve their practice more than going to a workshop or reading about it,” said Levine, a longtime principal who became chief academic officer in 2016.

School leadership came under a microscope too, with a revamped principal pipeline and a monthly dinner for new principals to share stories and advice.

Hands-on science projects and the arts also have been put back in the curriculum — along with related supplies and teacher training — after being pushed out over the years to accommodate more testing.

Supporting the changes has been Chattanooga 2.0, a coalition of nonprofit organizations, foundations and businesses that are championing learning from early childhood to career technical education. In January, a $1 million gift for middle and high school science labs was announced by Volkswagen, whose auto assembly plant is one of the city’s biggest employers.

In the years since the Benwood Initiative, a growing awareness has emerged in the community that it truly does take a village to turn around long-struggling schools — and to sustain those improvements.

“You don’t want to build a strategy around one person,” said Jared Bigham, who coordinates Chattanooga 2.0. “I think what has made this (latest) movement different is that we have every conceivable group at the table, or at least we’ve invited anyone who wants to engage.”

Over the summer, the school board tapped Johnson — the chief academic officer from Clarksville-Montgomery County schools north of Nashville — to be the district’s new superintendent. Working against a ticking clock, he has sought to find common ground between state and local leaders.

McQueen has made it clear that, one way or the other, the state will be involved in next steps. Two options are on the table.

The first is to place the five schools in a “partnership zone,” which would be the first of its kind in Tennessee. The initiative would be governed jointly by local and state officials, with the state having the biggest say. The plan would essentially create a mini-school district that’s freed from local rules to innovate as needed.

“The structure is not the magic bullet, but it creates some autonomy and accountability to move the schools forward,” McQueen said.

The second option is taking over some of the schools — and possibly eventually all of them — through the Achievement School District. The state-run district converts struggling schools into charter schools that are run by nonprofit operators. With schools in Memphis and Nashville, the so-called ASD has been Tennessee’s primary turnaround vehicle since launching in 2012. In Memphis especially, it’s been acknowledged for snapping complacent education leaders into action, even as it’s angered local stakeholders and shown less academic progress than locally led initiatives.

If the school board rejects the Partnership Zone option, McQueen says the district is essentially choosing to work with the ASD. The state would immediately begin plans to move Hamilton County’s two neediest schools — Orchard Knob Middle and Brainerd High — to the state-run district in the fall of 2018.

But community members are wary of state intervention of any kind. All year, they’ve packed school board meetings hoping for a third way, and Johnson obliged last month with a plan to create an “Opportunity Zone” for 12 struggling schools, including the five priority schools.

But he left open the door to still partner with the state on the priority school cluster. (Update: The school board voted Sept. 21 to move ahead with a partnership zone.)

Lessons and inspiration

Either way, the Benwood Initiative continues to provide a roadmap for the work ahead by showing what can happen when chronically underperforming schools have the right supports.

“If the work had been sustained, I believe we may not be having this conversation today,” McQueen told Chalkbeat. “The Benwood Initiative did a lot of things well that we would hope to implement, but in a more sustainable way and over more schools.”

That means targeted, evidence-based investments and interventions — and a community that’s willing to pitch in and help its low-income students.

In an ironic way, Woodmore’s fatal bus crash has set the stage by galvanizing the community to action. In the months after the tragedy, people from across Hamilton County joined with nonprofit organizations to volunteer and shower the school with resources — an example of what can happen when students, educators and other stakeholders work together.

“Out of tragedy sometimes comes good things,” said Levine, “because it brings out the best in people.”