How do teachers captivate their students? Here, in a series we call How I Teach, we ask great educators how they approach their jobs.

Don’t call Chikezie Madu a teacher. He prefers “facilitator.”

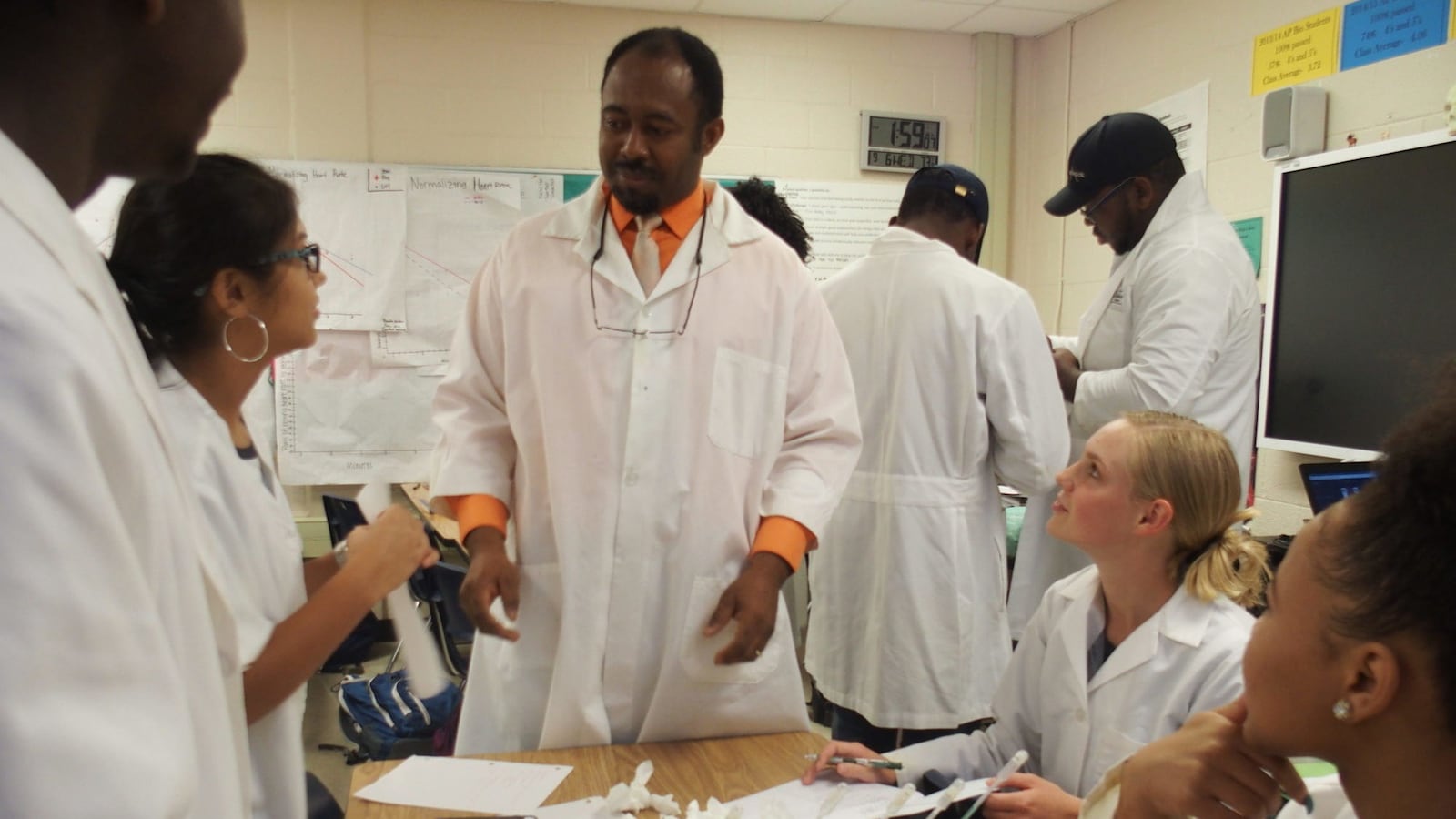

Madu is constantly moving around his biology classroom to foster solution-focused discussions with his students at White Station High School in Memphis. It might look like “organized chaos,” but it’s quite intentional, he says.

And it’s paid off. This year, he was one of seven Tennessee teachers honored with Presidential Awards for Excellence in Mathematics and Science Teaching, the nation’s highest award for teachers of those subjects.

Born in Nigeria, Madu’s path to teaching high school science has been a long and winding one. He taught music theory at a two-year college, then biology and chemistry at a military high school in Nigeria before joining his wife in 2002 in Memphis, where he began teaching middle school. He took a five-year detour as a cancer and genetics researcher at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, but missed mentoring and working with teenagers.

“They just want to learn and find what intrigues them,” Madu says. “I tell people I can’t believe I get to do this.”

In this installment of How I Teach, Madu talks about how he organizes his classroom and encourages students to learn from one another. This Q&A has been lightly edited for brevity and clarity.

Why did you become a teacher?

I delight in the challenge the job presents in coming up with ways of unraveling complex concepts, especially watching youth as their faces light up. Also, I have always cherished mentoring kids and have served in that role since I was in college. Finally, as cliché as this may sound, I was greatly influenced by my high school economics teacher, Mr. Emmanuel Adegoroye.

What does your classroom look like?

It depends on who you ask. To the traditional teacher, I may appear too hands-off. There may be too many students talking (sometimes all at once). It might seem informal with a lot of arguments and disagreements happening, students participating in most of the decision-making process, often cluttered.

On most days, I circulate and facilitate the entire class discussion, allowing the students to learn from each other. I believe that students learn best when they are actively participating in the lesson by explaining, solving, struggling, making mistakes and learning from them.

I couldn’t teach without my ________________. Why?

Visual aids or teaching models.

I use very common materials that students can relate to. For example, a hand-turning whisk may represent ATP synthase (or the enzyme that creates the energy storage molecule adenosine triphosphate) while two zippers stapled together depicts DNA replication.

Almost all students respond very positively to this tactile form of learning. Using common objects to represent intangible phenomenon is a key strategy across all fields of science. Using both hands-on and simulated materials serve as potent learning strategies because the students encounter the materials in their daily lives, triggering reminders of the concepts they learned.

How do you respond when a student doesn’t understand your lesson?

It can be frustrating if the student was distracted or was not in school during the early stages of the scaffolding process or does not know the right questions to ask to reveal where he or she needs help. We often figure out what the problem is by either back-tracking to where the confusion originated, asking another student to explain it in “teenage language,” using a different way to explain it, or sometimes all they need is a short break in the middle of a lesson.

I try to prevent that now by frequently checking for understanding every so often, asking the students to re-explain a concept I just did. The nod of a head never assures me that they understand.

How do you get to know your students and build relationships with them? What questions do you ask or what actions do you take?

Early in my career, I came to terms with the fact that I may not reach every child. But I try to spend some time with them outside the allotted classroom period. Many of them eat lunch in my classroom and we get to talk. I share my background with them. They know a lot about my kids. I give them my phone number, my house number and my wife’s number for them to reach me at any time. They often take me up on that offer. Someone called as late as 1 a.m. I also reveal my vulnerabilities. It’s not uncommon for me to let down my guard and act silly in class by breaking out in karaoke to the latest teen song or dance.

Just like life, adversity often builds strong relationships. A lot of times, a simple question about their struggling grades and expressing some empathy opens the door to a student’s many other struggles.

Tell us about a memorable time — good or bad — when contact with a student’s family changed your perspective or approach.

I have often been caught getting upset at a student and misjudging a situation or jumping to conclusions when a student appears to be “lazy,” only to find out that there was an underlying reason like problems at home.

I had a student like this once, where I was certain the student was just not “serious” about academics because they were frequently missing school, not turning in assignments and sometimes falling asleep in class. I eventually visited the home and was devastated at what I discovered.

Measures were taken to help alleviate the situation, and it was amazing the way things turned around. That was a huge learning moment for me. I’m learning daily to get the full story before jumping to conclusions and to determine if there’s anything I can do to help a student from failing the class. The student ended up graduating and going to college and turned out to be the first person to graduate from both high school and college in their family. We still keep in touch.