Third-grader Cassidy Nickelberg says the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. would be “sad and mad” about a major company’s decision to close a neighborhood grocery store in her South Memphis neighborhood.

So this week, she and about two dozen of her classmates at a Memphis charter school donned T-shirts bearing a photograph of the slain civil rights leader and went to the Kroger at the corner of Third and Belz to protest the decision by the Cincinnati-based grocery chain.

“We did that because we wanted to keep the Kroger open for the people who don’t have cars,” said Amiaya Davis, another third-grader at Vision Preparatory Charter School. “They may have to walk four or five miles to the next Kroger or ride the bus and they’re going to have to spend their dollars to go there, spending extra money.”

The children have been studying about King and his fight against poverty and inequity in preparation for the 50th anniversary of his assassination. Before being gunned down at the Lorraine Motel, King had come to Memphis in April of 1968 to help striking sanitation workers fight for improved safety standards and a decent wage.

Closing the Kroger will worsen a South Memphis “food desert” where it’s already challenging to buy fresh fruit and vegetables. About 60 percent of families in the mostly African-American neighborhood surrounding the store earn less than $25,000 annually.

“If (King) were here, he would have gone up to them and talked to them about closing,” said Cassidy in explaining why her class decided to emulate the minister’s strategy of peaceful protest.

Earlier this year, Cassidy, Amiaya and their classmates reenacted the famous 1968 photograph by Ernest showing Memphis sanitation workers holding up “I Am A Man” signs.

During their 45-minute protest on Wednesday afternoon, they wore T-shirts donated by the Withers Collection Museum and Gallery, chanted slogans, and carried signs saying “I Am A Child” and “I Need Fresh Food.”

Access to fresh food is a challenge in Memphis. The city ranked first in hunger in a 2010 Gallup poll that said 26 percent of Memphians could not afford food for their family at some point in the previous year. The Bluff City also had the highest obesity rate among cities with populations over 1 million, according to a 2013 Gallup index that measures wellbeing.

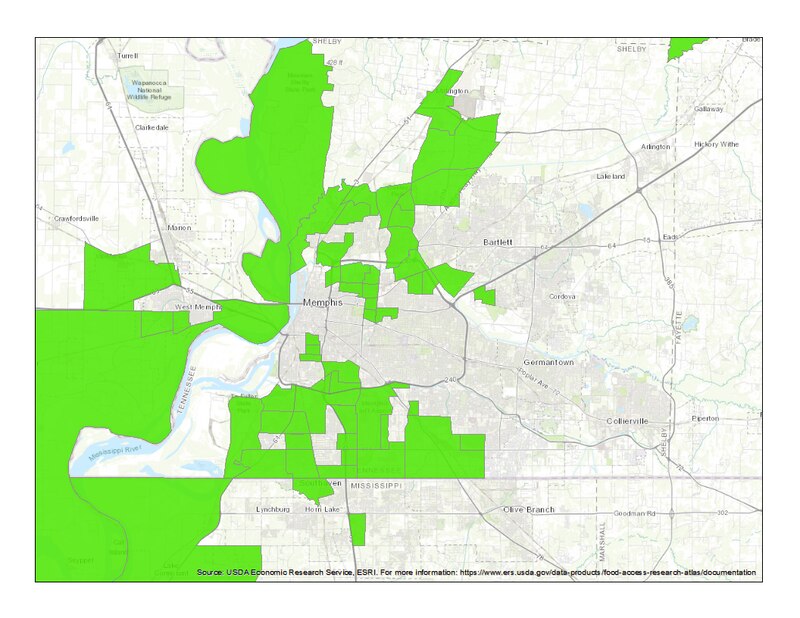

The U.S. Department of Agriculture defines a food desert as a community of at least 500 people in which more than a third of the population lives more than a mile from a large grocery store. The map below shows food deserts in Memphis-area low-income neighborhoods.

Officials with Kroger said its south Memphis store had lost more than $2 million since 2014. In its statement announcing several closures, they acknowledged the void the store’s departure would create and identified competing groceries nearby.

But parents and students said the closest option, a Save-a-Lot in the same shopping center, stocks a poorer quality of produce and meat.

Vision Prep Director Tom Benton said students at his charter school had been learning about food deserts prior to their protest to help them understand the bigger picture.

“There’s so much angst in the neighborhood about it and we see it every day. We felt we needed to do something,” he said.

Amiaya worries that more students will now come to her school hungry.

“You get fed at school but on the weekends when you want something, then you end up not having something. Then the only place you end up having something is school,” she said.

For more photos from the protest, visit Vision Prep’s Facebook page.