Roger Henery has come to realize that the students in the diverse Atlanta high school where he teaches tend to think racial conflict is a part of the past, not something that impacts them in the present.

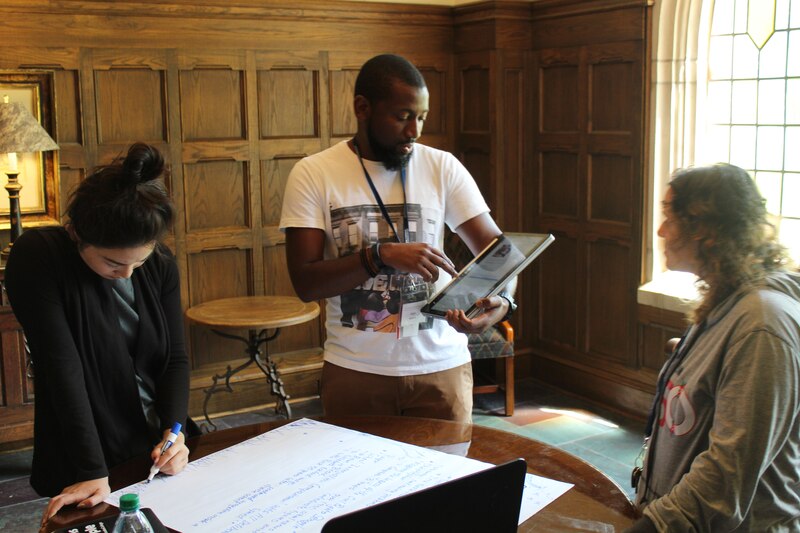

To change that, he’s one of 35 educators who participated in a class that taught him new ways to make history lessons about topics such as civil rights, race, and war more relevant for his students.

The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History’s Teacher Seminar program is a competitive professional development program for K-12 educators. For 24 years, several sites across the nation have become citywide classrooms for the program’s participants. Tucked away in a quiet Memphis neighborhood is Rhodes College, where, within its archaic stone walls, teachers – including one from Australia – met earlier this month to learn about the city’s rich civil rights history.

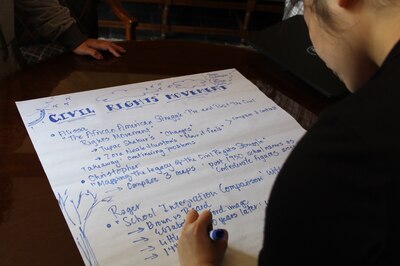

Lead scholar Charles McKinney, chair of Africana studies, and Noelle Trent of the National Civil Rights Museum, have organized the Memphis curriculum for three years. Participants examined archives and visited historic local sites such as the starting point of the 1966 March Against Fear, where activists marched 220 miles to Jackson, Mississippi, to promote black voter registration.

For a week, the teachers attended daily seminars taught by Memphis area activists and historians, and they were able to incorporate what they learned into potential lessons for their history and English classes. Through its strong network of educators, the program aims to support the teachers as they go back to their schools, some of which may be resistant to the new material, Trent said.

“It’s really the adults that have the issue with it,” she said. The program connects “with teachers to say, ‘Hey, you know, you can talk about these things with a kindergartener or pre-kindergartener… Let’s do it in a way that empowers them as individuals and as members of the society, and as our most vulnerable members of society.’”

Henery’s goal will be to show students how long it takes progress to actually happen, even after changes in the law have been made.

He plans to use old yearbooks to show how slowly (about 15 years) his Atlanta school aligned with Brown vs. Board of Education, the landmark Supreme Court decision that ruled racial segregation of children in public schools was unconstitutional. His class will look at footage shot 15 years after nine African-American students attempted to enroll in all-white Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas.

In another room, Doreen Lobelle showed her lesson to a group of elementary teachers in the seminar. She plans to have her fifth-grade students break down a speech by Joan Bird of the Black Panther Party and compare it to the story of Sandra Bland, who was said to have taken her own life after being forced out of her car by police and jailed for three days.

Lobelle noted that she’d have to edit the transcript for expletives, but that the subject matter was something her young students needed to learn.

“The point is, especially in the neighborhood that I work in, the kids are seeing themselves essentially in the kids that are being killed by the police all over the country,” she told them. “This is something that I have second graders talk to me about.”

Other lesson plans included reading lesser-known speeches by Martin Luther King, Jr., studying female activists and how they often lacked the visibility of their male counterpart, and observing street signs and schools named after Confederate soldiers.

Embedded in many of those lessons, McKinney noted, is a call to action to confront a “national commitment to avoidance,” by starting to teach children at a young age parts of history that still are being left out of classrooms.

“It literally doesn’t make any sense to me to say, okay, we’re not going to talk about dynamics that are shaping your life in profound and fundamental ways…. We’re not going to talk about those dynamics until you get to high school, or later…. And that’s a problem,” he said.

But even before the teachers had started to work on the lesson plans they would take home with them, they were reminded that they still have a lot to learn.

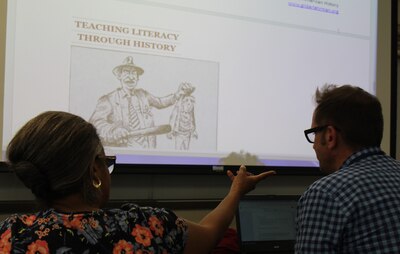

“I’ll bet you five dollars that you can not tell me who these 10 people are,” Master Teacher Justin Emrich said to the 35 participants, pointing to the the names of historical figures on a screen: Julius Caesar, Adolf Hitler, Ghengis Khan, George Washington, Osama Bin Laden, Paul Rusesabagina, Tarana Burke, Harvey Milk, Raphael Lemkin, and Ben Ferencz.

As the teachers struggled about halfway through, he explained that the list was divided between those who “kill people; they’re known for war,” and “bringers of peace.”

Emrich, who was 2016 Teacher of the Year in Ohio, urged the group to think about who they’ve been teaching about in their history and English classes, and how that might change.

“Devote yourself to telling about the other people, from day one,” he said. “… It is the only way we can get our students to do the same.”

Henery, who has been teaching for 12 years, will come back to his classroom with a new perspective on history.

“I came here expecting to learn an awful lot, and I learned probably five times more than that,” he said.