Fifty years ago, one of the largest and longest protests held in Memphis centered on education.

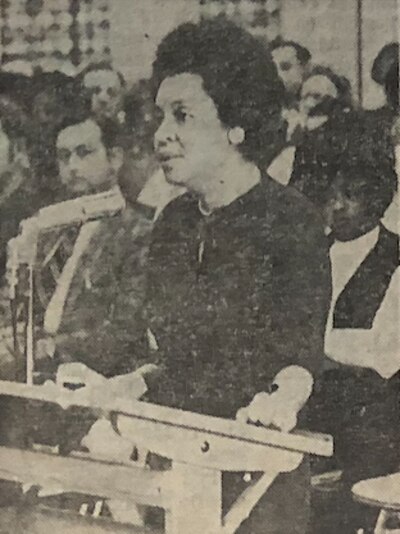

The protests, known collectively as Black Monday, called for parents to take their children out of school during at least five Mondays in the fall of 1969 and march in support of 15 demands the NAACP submitted to the Memphis school board. Because school funding, then and now, was tied to student enrollment, black leaders sought to “pull at the purse strings” of the district to meet demands, said protest organizer Maxine Smith in a 2004 interview.

The city had grabbed the national spotlight a year and a half earlier when civil rights icon Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated at a Memphis hotel. But even the large crowd that marched to City Hall in support of the sanitation workers’ strike after King’s assassination was smaller than the Black Monday boycott.

Based on 1969 news reports, almost 67,000 students did not attend school at the height of the protest as black leaders advocated for seats on the all-white school board. They also were pressuring the district to promote black educators so they could have a greater say in decisions and make good on a federal court order to desegregate schools. Makeshift classrooms were set up in community centers and churches so students wouldn’t fall behind in their schoolwork.

The boycotts resulted in the school board appointing two black advisors, a black assistant superintendent, and a black coordinator to a central office position, according to protest organizers and research by James Conway, a former history professor at the University of Memphis.

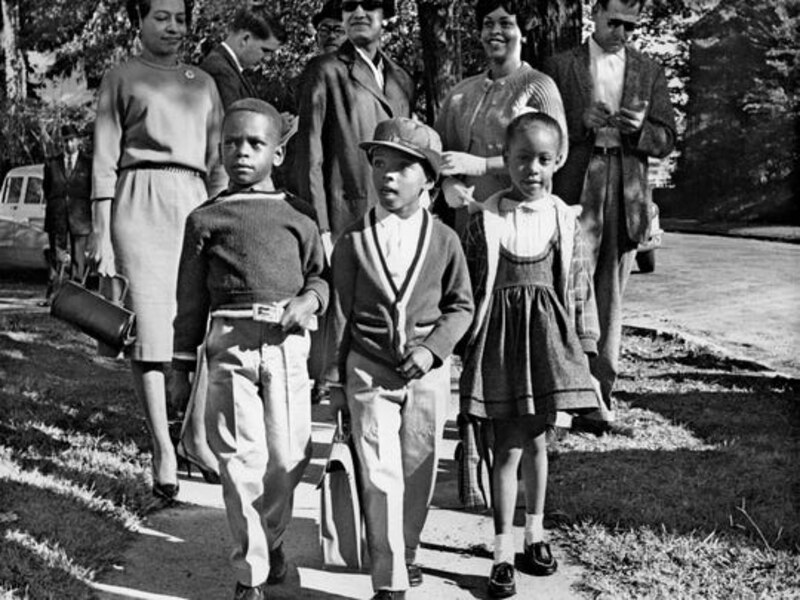

The protests also boosted the confidence of local civil rights leaders that trickled down to students in the classroom, said Dwania Kyles, one of the first black students to attend an all-white elementary school in 1961. Kyles was 13 years old during the Black Monday protests and recalled an example of black girls trying out for an all-white cheerleading squad.

“Before, you wouldn’t even go and try out because you knew you weren’t going to get picked,” she told Chalkbeat. “When Black Monday came along, we felt more empowered to go and do things,” even if they still were rejected.

“And now we’re going to question you about it. What was that decision based on?” she continued. “If you’re not showing up, you don’t get to say anything. There had to be a conversation. It’s an evolution.”

Smith, who later would become the first African-American elected to the school board two years later, organized the massive protest alongside Laurie Sugarmon, education chairwoman for the NAACP and another local activist group the Mobilizers. Sugarmon has changed her name to Miriam DeCosta-Willis; Smith died in 2013.

DeCosta-Willis now says she has seen significant progress on some of the demands, but many of the same issues still exist in Memphis education today. She said she hopes to see more activism.

“What we have is a white flight to private schools and the emergence of separate schools in Germantown and Collierville and the resegregation of Memphis schools,” she said of the mostly white suburban exit of six districts in 2014. “I’m very angry about that. The equality and justice we strove for in the ‘60s has not been realized.”

Below is a summary of the NAACP’s demands and where they stand today:

Desegregation

Two demands proposed ways to desegregate Memphis schools. The first was to work with the NAACP to split the 134,000-student district into three or four smaller school systems that were racially mixed. The second was to pair nearby white and black schools and mix their enrollment.

“They talk about the slowness of [desegregation], the resistance of it,” said Earnestine Jenkins, a professor at the University of Memphis who was part of a small group of black students to first integrate Whitehaven Elementary School in 1968. “So, there wasn’t going to be desegregation unless it was forced.”

Busing students en masse to other schools within the district to achieve racial integration wouldn’t come until four years later under a court order. In response, many white families, who made up about half of student enrollment, fled to the suburbs and private schools.

Now, only 7% of Shelby County Schools students are white, making mass integration within the district impossible. Most white people in the county are still in the suburbs and district boundaries separating the city and the six municipalities cement the divide. All but one of the suburban districts are majority-white, despite a black majority in the county.

Leadership

Protesters also called for at least two members of the school board to resign to make room for black representatives, and appointments of black educators in prominent leadership positions.

The NAACP argued that black administrators and teachers should be in proportion to the share of black students in the school system. At the time, about 54% of students were black compared with 44% of teachers.

They also demanded that black teachers make up three-fourths of new hires. African Americans felt talented black teachers were being removed from their schools as the district started reassigning experienced black teachers to white schools and replacing them with inexperienced white teachers.

Now, more than three-fourths of administrators in Shelby County Schools are black, according to state data from the 2018-19 school year — about the same percentage of black students in the district. Nearly 60% of teachers are black and about a third are white.

The proportion of black administrators and teachers in suburban districts range mostly from 10% to 20%, with similarly low shares of black students. Lakeland, the smallest of the municipal districts, is a notable exception. Twelve percent of its students are black, but a third of its administrators are black. Black educators in the state-run Achievement School District, which took over low-performing Memphis schools in an effort to improve them, make up about 53% of teachers and 65% of administrators, compared with 93% of students.

And now seven out of nine school board members are black.

Curriculum

Three demands called for more black representation in class offerings, textbooks, and books available in school libraries.

African-American history classes are on Tennessee’s approved list of high school electives and taught in several Memphis schools. And it’s common to see black main characters prominently displayed in school libraries.

During the state Board of Education’s most recent round of updating what students should learn in social studies class, more historic black leaders were added, though most of the conversation centered on balancing lessons on world religions.

Still, some advocates say there’s more room to grow. For example, former Shelby County Schools student Jazmyne Wright recently started a petition to include natural African-American hair in cosmetology classes. District officials told The Memphis Flyer that the state determines course materials.

“I think ethnic hair should be just as much a default in cosmetology as any other hair texture or origin,” she said in her online petition that has garnered about 350 participants. “Black students should be able to learn about their community’s hair and even how to take care of their own hair.”

Related: Why one Memphis principal reads bedtime stories to students via Facebook Live

Other

Lastly, the NAACP’s demands called for free or reduced-price lunches to be available to all families living in poverty and that school board meetings be televised.

All students in Shelby County Schools now qualify for free breakfast and lunch because of a federal program designed for high-poverty districts.

And you can find school board meetings live streamed on the Voice of SCS or listen on the district’s radio station, 88.5 FM.