There’s still three weeks before school starts in Memphis, but on a recent afternoon, the parking lot at Hickory Ridge Middle School was packed.

Veteran kindergarten teacher Sandra Jenkins pulled up at 3:17 p.m. and parked her sage green Toyota Corolla along a curb on the campus outskirts. At Shelby County Schools district’s biggest job fair of the year, other prospective teachers had already taken every spot before the massive hiring event officially started at 3 p.m.

Ninety-seven percent of district positions are already spoken for. But a few positions in every grade and almost every subject remain open. This is the fifth teacher job fair in the region Jenkins has attended in the past 12 months. So far, she’s only been able to land substitute positions, but she’s hoping to go home from this hiring event with something more permanent.

For schools with vacancies, this time of year is “crunch time,” said Desmond Hendricks as he set up an interview table in the school gymnasium. He is a social studies teacher at Raleigh Egypt Middle School and was waiting to field candidates for five open positions in math and English. “It’s all about finding the right fit,” he said.

Hendricks joined about 75 other district schools in the gymnasium and cafeteria, preparing to interview candidates and make tentative hiring offers for dozens of vacant positions in Tennessee’s largest district.

Jenkins, 60, is hopeful she’ll be a good fit for one of those schools. The Memphis native is just one of the 224 people who showed up at the two-hour event, hoping to nail down a full-time job before school starts in mid-August. But her silver-streaked ponytail set her apart from the mass of relatively young-looking, recently certified teachers — many of whom were probably born after Jenkins started her first long term substitute teaching job at Whitehaven Elementary in 1981.

“We didn’t have job fairs back then,” Jenkins recalled, as she carefully walked through the parking lot in her marshmallow-white tennis shoes and compression socks. “We just applied to the district and got hired. Now it’s all politics and paperwork.”

As she opened the heavy double doors to start her job hunt, Jenkins passed a young, well-dressed woman skipping back into the parking lot, gleefully proclaiming, “I got the job!” into her cell phone.

“It feels like they only want young ones now,” said Jenkins, who has more than 30 years of classroom experience in Memphis public schools.

Jenkins’ age and experience level make her an outlier in the Memphis teacher workforce, which is plagued by high turnover that creates a pool of inexperienced educators. In the 2015-16 school year, approximately one in five Tennessee teachers were in their first or second years of work, according to data that schools reported to the federal government. Those figures were even higher in Memphis.

Jenkins came armed with a manilla folder containing a stack of resumes and a pitch about herself. Helping young students reach their highest potential is her broad goal, but her specific goal is to get back to teaching kindergarten. She did that for 22 years until a car accident forced her into an unexpected, early retirement from her position at Holmes Road Elementary five years ago. She took some time off to be with family and care for a now-deceased neighbor.

“I’m trying to get back into teaching, but it’s been hard,” she said.

For Jenkins, who has no children of her own, kindergarten is the only grade she can see herself teaching. “They are like my kids,” she said, as she waited in line to check in with district staff and verify her certification. “Some children that I have taught were complete blank slates when they walked into my class. I like molding them, shaping them, building their confidence.”

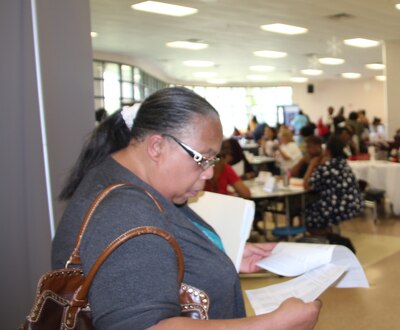

A district employee hands Jenkins a printout of the job openings, directing Jenkins to the school cafeteria for K-8 openings.

She scans the list looking for kindergarten openings while she walks down a corridor toward the lunchroom. Instead of sandwiches and juice boxes, job ads and interview questionnaires are strewn across the circular tables. School personnel are seated on the built-in benches, ready to interview teachers, ready to make offers.

Jenkins snakes through the maze of teachers and administrators. “I knew I’d see a bunch of people I know,” she said, smiling after spotting an old colleague, Sarah Hamer, who now works as a professional learning coach for White Station Elementary. Hamer’s looking to hire for first grade — not quite what Jenkins is looking for. “I get it. When you’re a kindergarten teacher, you’re a kindergarten teacher for life,” Hamer said to Jenkins. “If you change your mind, we’d love to interview you.”

Jenkins drops off a few resumes at other tables, careful not to interrupt interviews. Then, finally, she gets invited to sit down at the Sheffield Elementary School table for five minutes. The school has an opening for kindergarten, but they’ve already interviewed a few other candidates. They said they’d keep her resume on file.

“If people don’t like me, I move on,” Jenkins said. “Rejection doesn’t hurt me. I was one of the first black students to integrate Whitehaven Elementary in 1967. I got spit on, called names. I don’t take it personally.”

The big round clock on the white cinder block walls ticks to 4:55. By that point Jenkins had handed out almost every copy of her resume, and the crowd is thinning.

On her way out, she bumped into another former coworker, now-assistant superintendent Rodney Rowan. Jenkins told him the day hadn’t gone as well as she’d hope.

Rowan seemed surprised. “I would hire a seasoned teacher in a heartbeat,” he said, “because they don’t require as much training.” He said Jenkins could list him as a reference and he’d tell the schools: “You love children. You work hard. You stayed until the job was done. You didn’t watch the clock.”

As of 5 p.m., when the job fair ended, district recruitment and staffing associate Sheilaine Moses said they’d received 40 hiring recommendations, pending district approval. Jenkins’ name wasn’t among them.

“There’s still a few weeks before school,” Jenkins said as she walked out to the far end of now-emptied school parking lot. “It will happen if it’s supposed to.”