Rodney Robinson will never forget how isolated he felt as one of the few black faces at his Virginia high school.

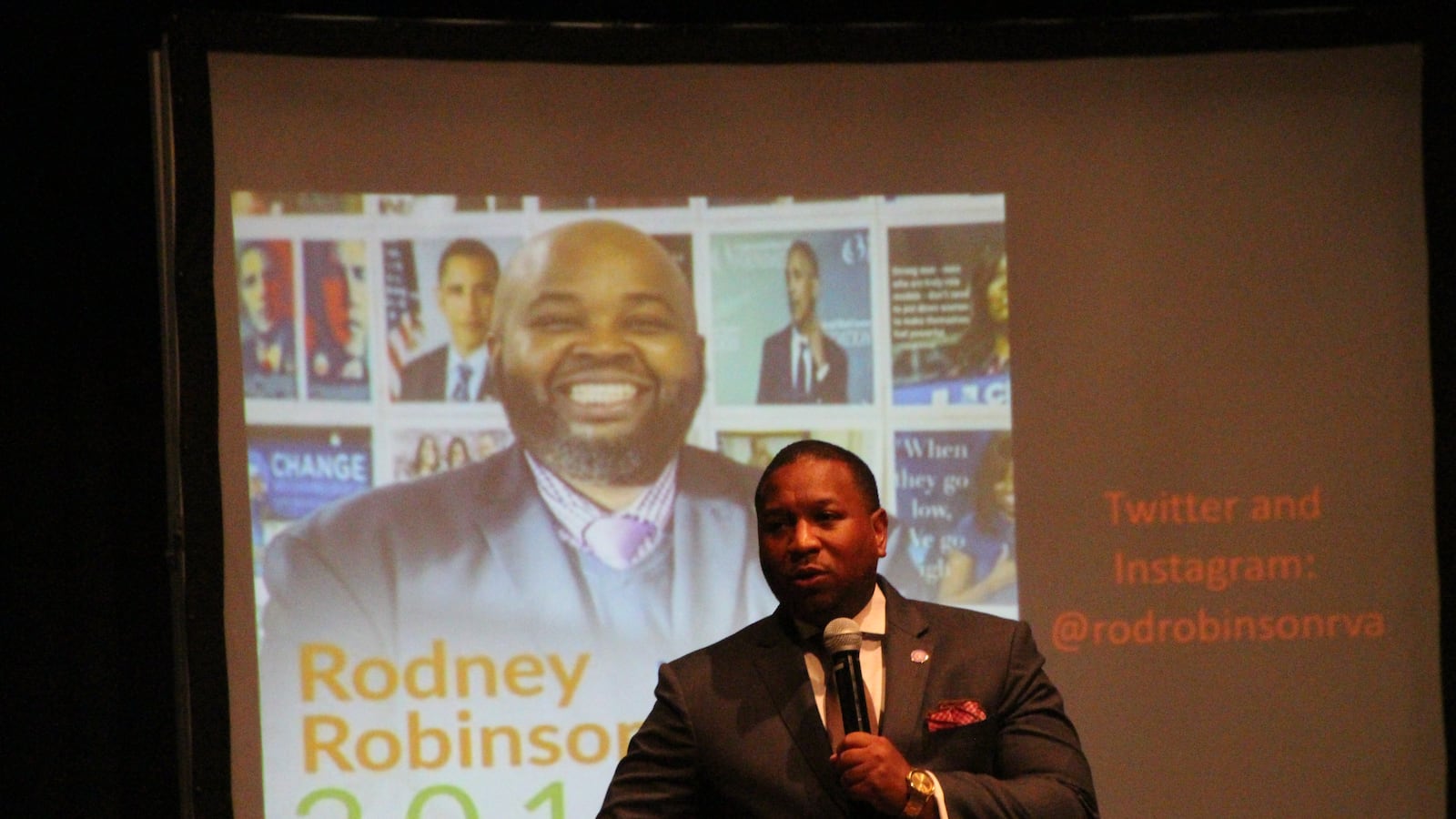

“Growing up as the smart black kid in a white school is traumatizing,” said Robinson, who was named 2019 National Teacher of the Year. He spoke to more than 200 Shelby County Schools educators and summer school students at Southwind High School earlier this week as part of a two-day districtwide training.

Robinson, who teaches social studies at the Virgie Binford Education Center, located inside the Richmond Juvenile Detention Center in Virginia, recalled how as a high schooler that trauma came to a head in the mid-1990s when a white teacher made a racially insensitive remark.

“In my anger I turned over a desk,” Robinson told the audience who attended his presentation Tuesday.

“The teacher sent me to the assistant principal’s office,” he continued. “I was scared because the code of conduct said damage of property could result in expulsion,” said Robinson, who has written extensively about rethinking school discipline.

Robinson’s experience resonated with local school officials, who are focusing new attention on ending Memphis’ school-to-prison pipeline, or punitive discipline tactics that can lead to higher rates of incarceration, especially for black boys. In the 2017-2018 school year, Shelby County Schools issued almost 2,500 expulsions, according to district data. That’s about 300 more than in the previous year — when, according to federal data, the district already had one of the highest expulsion numbers in the country.

“I care about all 110,000 students in Shelby County Schools,” said superintendent Joris Ray in a speech ahead of Robinson’s presentation. “But this priority group [of black male students] needs us the most.” Black boys, who make up about 38 percent of the district’s more than 100,000 students, accounted for 67 percent of expulsions in the 2017-18 school year.

“Relationships are the key determinant in changing student behaviors,” Ray said after the event. “For students to succeed in school, someone has to show interest in them, and set high expectations.”

Hiring more black male teachers, who make up 9.5 percent of the district’s workforce, is critical to making that happen, Ray said. He is about to start his first full year as superintendent and said next week he will give more specifics addressing the systemic barriers that have impeded the academic achievement of black male students.

Although the problem of black male students facing suspensions and expulsions at a disproportionately higher rate than their white peers is especially prominent in Memphis, it has pervaded nearly every district, city, and state in the country for decades.

But Robinson’s story had a better outcome than those statistics suggested it would, which he attributes to having a strong, relatable mentor. The assistant principal, Wayne Lewis, was one of a handful of black authority figures working at Robinson’s school.

“I sat down in front of Dr. Lewis and he asked me ‘where are you thinking about going to [college]?’” Robinson said.

The comment surprised Robinson. He was bracing for a harsh punishment, but instead Lewis told him about Virginia State University, where Robinson received his bachelor’s degree in history several years later.

Then, the conversation circled back to the reason Robinson was in Lewis’ office. He said he wasn’t going to suspend Robinson because “he knew I was going to go home and do something stupid. But he told me I couldn’t curse at teachers and flip over desks — no matter how upset I was — so he gave me in-school suspension instead.”

And when Robinson showed up for his in-school punishment, Lewis did, too, carrying college application materials.

“He took time to get to know every student on a personal level — black and white,” Robinson said. “He took me from a confused teenager to a confident young man. He showed me what a black man should be,” Robinson said.

Now in his 40s, Robinson said all students, especially black boys, need more culturally responsive, empathetic teachers. “Our kids are coming into our schools dealing with problems we can’t even imagine,” he said.

Although his students are already incarcerated, he suggests a four-pronged teaching approach that can be applied to teachers in any classroom, regardless of the demographic of students they serve:

- Don’t put students in a box — get to know them as people.

- Make learning relevant.

- Create new experiences.

- Be a mentor.

District leaders are already working to putting those practices into action to prevent students from ending up in a juvenile detention center like the one where Robinson works.

“Kids don’t wake up one day and end up in a situation like that,” said Angela Hargrave, director of the district’s Office of Student Equity, Enrollment and Discipline, which organized the teacher workshop.

“It starts with addressing some of the minor behaviors first,” Hargrave said. “We want to make sure our first response is about support not punishment.”