Growing up in the early 1970s at the Lincoln Apartments in North Memphis, Jacqueline Hill-Ferby didn’t know many white people. “At least I don’t remember any,” she recalled some 46 years later.

All that changed in 1973.

Memphis City Schools, like scores of other districts across the country, implemented a court-ordered busing policy as part of the most radical attempt to integrate once legally segregated schools in United States history.

Conversations about busing and what courts and communities should do to create integrated schools have been back in the news after a tense exchange between U.S. Sen. Kamala Harris and former Vice President Joe Biden during the Democratic debates.

In response, we asked our readers to share their experiences with busing in Memphis. Some Chalkbeat readers described feeling invigorated by exposure to new people and ideas, disheartened by hostile reactions to integration, and confused about busing.

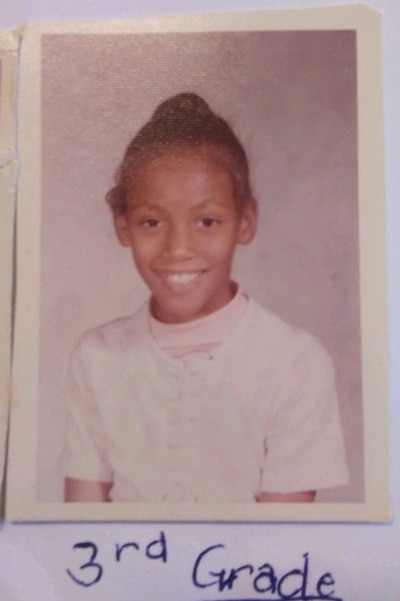

Hill-Ferby was in third grade when she was notified by the district that she would be one of more than 40,000 students in Memphis transferring to a school across town beginning in the 1973-74 school year. Instead of attending nearby Hyde Park Elementary, a school bus would take her on a 45-minute ride to Raleigh-Bartlett Meadows Elementary.

“Riding the bus to our new school, Raleigh-Bartlett Meadows, allowed me to experience life outside of the ‘projects’,” wrote Hill-Ferby, who had not ventured further than downtown Memphis before that point.

And when she finally arrived at the school, something else happened.

“It introduced me to white people. This was the first time that I had been exposed to white people on such a large scale,” she said.

With that introduction came, in theory, equitable access to public education, a reality that had eluded black Americans since the inception of modern public school systems a century before.

Beyond academic resources, integrated schooling also shaped her relationships.

Hill-Ferby developed her first crush “on a blue-eyed little boy named Bobby” at an integrated school. She found one of her first professional role models in a black teacher named Mrs. Glover, at an integrated school.

“Everyone said that I looked ‘just like the teacher.’ I was the only black girl in my class, so that was no surprise. By then, I had latched on to school, where I thrived. I knew then that I HAD to become a teacher,” said Hill-Ferby, who is about to enter her 29th year of teaching in the Memphis area. “I feel that busing was a positive experience that changed the course of my life for the better.”

Hill-Ferby’s positive experiences in those integrated classrooms were the culmination of a fight twice her age at the time.

In 1954, about ten years before she was born, the U.S. Supreme Court’s unanimous opinion in Brown v. Board of Education declared inherently unequal, and thereby unconstitutional the binary school systems operating in Memphis, and nearly every other school district in the country.

"It opened up a whole new world for me... a world of houses, big houses with lawns, backyards that had swimming pools, and houses that had garages and carports."

Jacqueline Hill-Ferby

After two decades of court battles, violence and stall tactics, the 1971 Supreme Court ruling on Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education finally created a framework for integrating schools: Court-ordered busing. It would require districts across the country to transport students across town to achieve racially mixed student bodies. Memphis students returned from the holiday break in January 1973 to a court-mandated busing program which lasted in some fashion until as recently as 2009.

“I was terrified,” recalled Renee Winton who had attended East Junior High School during sixth grade when she learned that she’d be transported across town to Craigmont Elementary the next year. “That was the worst summer ever. I was older and had my experiences with racial tension and prejudice. I cried. I begged my mom not to make me go. I feared being somewhere I wasn’t wanted. I literally thought I would be hung or killed.”

When the school year finally started, Winton said that “In all of my classrooms, blacks migrated toward each other so [we] were segregated within the integrated schools. I think we sat near each other for a sense of safety and security.”

For better or worse, busing in Memphis changed lives.

Reginald Fentress, who transferred from Cypress Jr. High in North Memphis to Trezevant Junior High, said it “was a disaster from day one.”

“It was a highly traumatic experience,” recalls Fentress who said that was the first year he’d ever been held back a grade. “I actually saw ‘n—– go home’ signs posted up. We were so disconnected from the school. Many teachers didn’t want us there and we knew it.”

Looking back, Fentress characterized busing as a “a failed experiment” because it made him “realize how valuable neighborhood/community schools are. When there is a relationship between the school and the community it impacts relationships and supports teaching and learning.”

By 1978, 40,000 white students — more than half of those enrolled in 1970 — had left Memphis city schools, a move that directly contributed to Memphis’ distinction of having one of the largest private school systems in the country. To this day, Memphis schools remain starkly segregated, with 90 percent of students enrolled in 2018 identifying as black.

Chris Moth was one student who left the district for a private school. He had been attending his neighborhood Balmoral Elementary, but when the busing orders came, his parents refused to participate.

Like so many others, Moth’s parents enrolled him a private Christian school rather than send him on the “10-mile bus trip to a part of town with a reputation for violence, and a school building strongly rumored to be in decay.”

But “the horror and disruption of busing has strongly colored” Moth’s advocacy for integrated public education. He’s twice run for the state House of Representatives on a campaign of educational equity.

Peggy McClure was another student who left the district after her family learned that she’d be bused from a junior high school in East Memphis to the north side of town. “It was not a good option to be college-ready, so my parents chose to send me a year early to an independent school,” McClure recalled.

She believes she received a top-notch education at her new school, but the social dynamics she observed there still give her pause: “To this day many of my classmates who never experienced public school STILL cannot relate to or empathize with those of significantly lower socioeconomic status.”

Denise Davidson, who was only 10 years old in 1973, will never forget the day her teacher told her she would not be returning to her school in the Raleigh neighborhood the following year. “I didn’t understand and became very upset. When I got home that day, I asked my parents about it. They told me that the teacher was right, but that I would not be attending ANY Memphis school, because we were moving,” Davidson said.

Her mom told her that if they stayed in Memphis, Davidson and her two siblings would be bused to three different schools. “My parents were not going to let that happen, so we moved out of Memphis. We became part of what became known as white-flight.”

Busing continued for decades in Memphis, and became a curious fact of life for some children.

“I always thought it odd that I was bused over 20 minutes away from the Capleville/Whitehaven area where I lived,” recalled Kenya Payne who attended elementary school in Memphis in the late 1990s.

“By the time I made it to middle school, things had gotten so bad that my parents searched for alternatives,” she said, describing her move from Kirby Middle School to a magnet school as different as “night and day.”

“My parents had to make so many sacrifices to allow me to have access to that opportunity just so I could have a quality education.”