When Tennessee’s middle school social studies teachers return to their classrooms this August, they’ll still be required to teach about world religions. But the new state standards leave less room for interpretation.

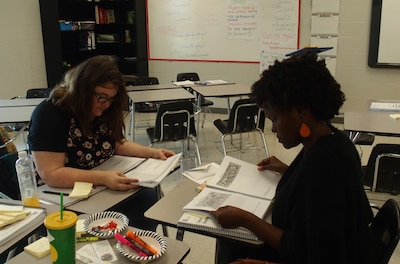

“We’re not here to indoctrinate our students, but to educate them,” social studies teacher Zan Brennan said during a recent two-day teacher training she attended at Arlington High School, just outside of Memphis.

“A lot of students are curious about the different religions,” added Brennan, who works at Memphis Business Academy, as she joined dozens of other social studies teachers from across West Tennessee last month to learn about changes to the state’s social studies standards. The requirements set the framework for individual districts, schools and teachers to shape instruction and curriculum.

Aside from revisions to seventh-grade benchmarks for teaching about world religions, the standards will seem familiar for the most part, with a few exceptions. Two examples: All fifth-graders will learn about Tennessee history in a new, self-contained course. Peppered throughout the standards for multiple grades are mentions of historically underemphasized figures such as black entrepreneur and activist Madam C.J. Walker. Her story is now part of the 11th-grade U.S. history standards.

The rollout will mark the end of a four-year-long saga of reviewing and revising Tennessee’s social studies standards, which was catalyzed in part by controversy over how world religions were being taught.

In 2015, the fine line between education and indoctrination grabbed national headlines and the attention of some school board members and state lawmakers as parents complained about the way that Islam was being taught. In a state where Christianity is the dominant religion, the teaching of Islam was at the center of the controversy.

“It is reprehensible that our school system has exhibited this double-standard, more concerned with teaching the practices of Islam than the history of Christianity,” then-U.S. Rep Marsha Blackburn said at the time. “Tennessee parents have a right to be outraged and I stand by them in this fight.”

The old middle school standards included varying guidelines on how to address the six world religions taught in world history courses — Islam, Judaism, Christianity, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Shintoism.

“We have social studies standards that cover world religions, but we are explicit in those standards that no proselytization can take place,” said Nathan James, legal director of the Tennessee State Board of Education, which ordered the review. “We’re not in the business of making new members of any particular faith … I would argue that was clear before, but nothing’s clear for everybody.”

Nonetheless, the disputes contributed to an early revamp of the 2014 social studies standards, which were only two years old at the time.

Standards for all subjects are typically revised every six years, but public concerns over religion and less-talked-about, yet widespread teacher qualms over the sheer volume of standards set that process in motion in late 2015.

The state assembled public officials and teams of K-12 and post-secondary educators to review a total of 141,000 pieces of public feedback to shape the changes.

One of the results of that process is clearer standards for teaching religion. Each of the six creeds students are required to learn about now follow the exact same formula: origins, key people, sacred texts and basic beliefs.

“The standards weren’t biased before, but now it’s more specific that each religion needs to be covered a certain way,” Brennan said.

Bill Carey, who founded the nonprofit Tennessee History for Kids and served on the 10-member social studies standards recommendation committee, said that was one of the intentions of the rewrite. “We wanted to make it clear to teachers that they’re just supposed to teach the story of the religion. When I first saw the old standards [in 2014], my first thought was we’re going to see a lawsuit filed because the standards were so broad.”

The new standards have tightened the lid on that concern, but “there are some people who will make that complaint or accusation no matter what’s in the standards,” he added.

Religion-related standards aren’t the only changes teachers and students will see starting this fall. Amid the years-long standards rewrite, the Tennessee General Assembly in 2017 passed a law mandating a specific state history course be added to the lineup of required social studies courses. In recent years, state history has been integrated throughout the standards. But starting this school year students will take the new state history course in the second half of the fifth grade.

“That’s a big change because in the past, fourth-grade teachers had to teach U.S. and Tennessee history to 1850,” Carey said. “Fifth-grade teachers taught [from] 1850 to the present. As a result of these changes, every fourth-grade teacher will now have to teach the Civil War and most of them have never done that. Every fifth-grade teacher in the state will now have to teach a standalone Tennessee history course and most of them have never done that.”

Shelby County Schools spokesperson Jerica Phillips said in an email that “because of the shift in the content for each grade, gaps could occur for the 2019-2020 school year.” Last spring, the state’s education department provided the district with “gap units” to fill in some of those holes. Fourth- and fifth-grade social studies teachers will use those same units to get students up to speed during the first few weeks of this coming school year.

But across K-12, condensing the standards, affording flexibility in the curriculum for individual class needs, and emphasizing more analytical and critical thinking skills are some of the biggest differences.

“The main goals we had at the start of the process was to streamline the standards. That was a lot of content to cover,” said Brian Davis, who served on the educator advisory team, which took the first pass at the public comments and made recommendations to the standards recommendations committee. “In 11th-grade U.S. history, for example, we narrowed it down from 112 to 95 standards. I’d still like to see fewer standards.”

Davis was a teacher at Whitehaven High School in Memphis when he first got involved in the revision process in the summer of 2016. He’s now the high school social studies adviser for Shelby County Schools.

“We also took out a lot of the prescribed curriculum in a lot of the standards. For instance, the third standard in ninth-grade world history was to do a research project on the French Revolution. That was problematic because three weeks into school you had students doing a major project they might not be prepared for,” Davis said. “Specific projects and assignments largely disappeared from standards, and teachers have more autonomy in the classroom.”

How educators should frame the discussion about a specific standard — whether through an economic, geographic, or political lens — is now more prominently displayed.

“Once you start getting all these different things tied together, the kids are going to be able make deeper connections about how the past affects the present,” said Cordova High School history teacher Brian Huber, who led one of the standards training sessions.

Teachers who have seen the new standards agree say they are better, said Rafael Rodriguez, a history teacher at Halls High School in Lauderdale County. “They make more sense, and they’re easier to use as a teacher,” he said. “If I would have had these last year, it would have helped. It’s a little more clear.”