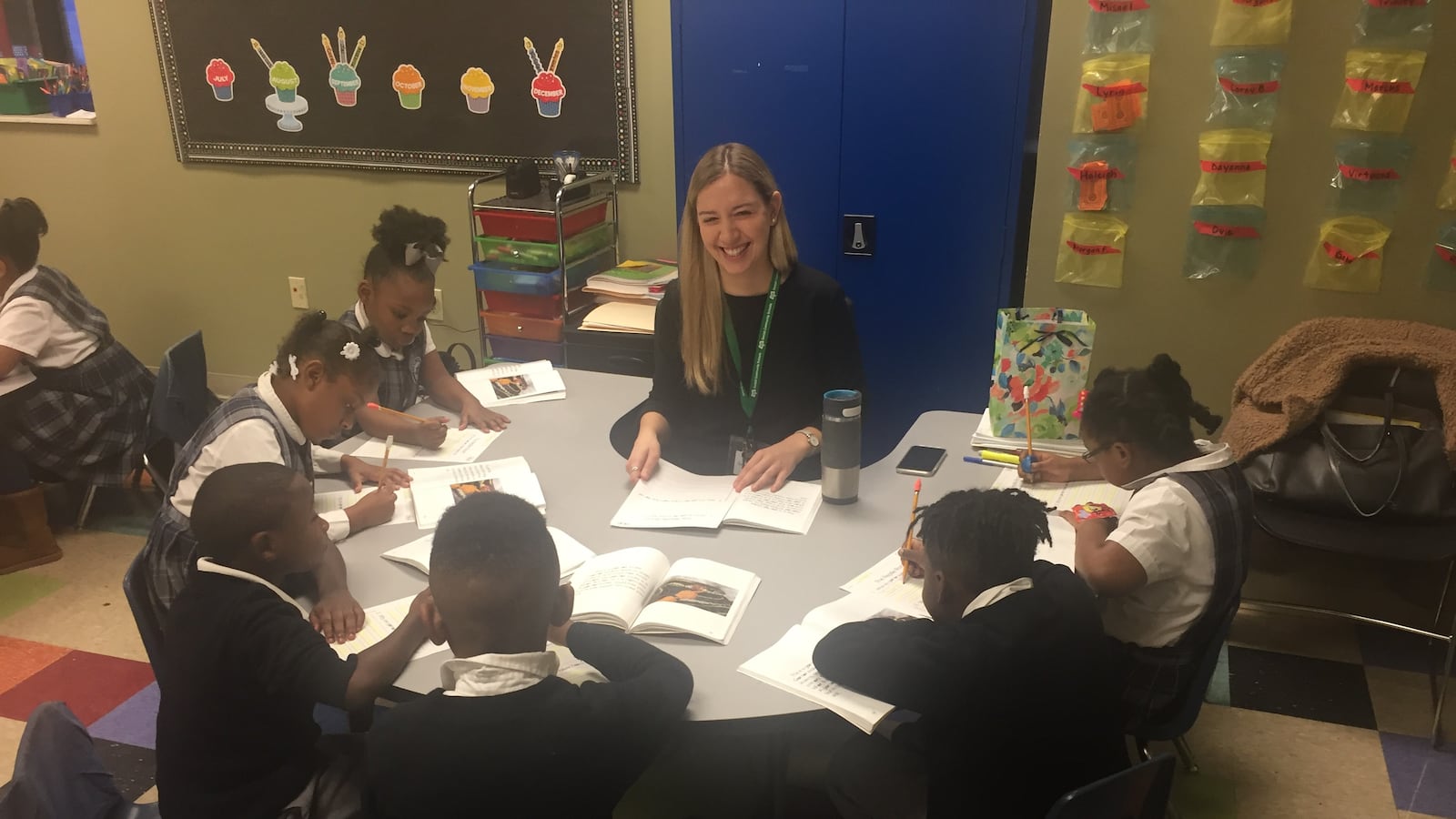

Cultivating meaningful relationships with students and their families is equal parts challenge and reward for first-grade teacher Lauren Jolly, a member of Teach for America’s Memphis Corps.

“No matter what my actions may be, I need to explicitly state to each and every family in my classroom that I care about their child,” Jolly said.

It’s a lesson she first learned as a private piano teacher in Ohio and it’s one she has continued to realize now that she teaches at Power Center Academy Elementary School in Hickory Hill.

“I will do everything I can to help my students succeed but most importantly I need to express to the parent I am on their side,” she said. “We are teammates in this fight for educational equity.”

For this installment of How I Teach, we asked Jolly to tell us more about what she learned during her first year of classroom teaching and how she’s incorporating those lessons into her work. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Was there a moment when you decided to become a teacher?

There wasn’t an exact moment when I decided to become a teacher, but rather something that occurred over time. I graduated from Ohio State University with a degree in Piano Performance and decided before pursuing a graduate degree in music, I wanted to teach private piano lessons for a while.

In less than a year I had built my piano studio up to 50 students. I was constantly asking myself what I could do to help my students learn faster and to love playing piano. I would go home and make flashcards, create games and incentives to foster a fun-loving learning environment. I had no idea that I would genuinely enjoy teaching as much as I did.

A big part of what made my job so enjoyable was the relationships I formed with my students and their families. The only downside was I would only see each student once a week for 30 minutes. At this point, I realized I wanted to make my way into the classroom setting so I could spend more time with my students but still continue to develop and foster their love for life-long learning.

How do you get to know your students?

One of my favorite events that I do in my classroom once a week is “lunch bunch.” Every Friday, I pick five students who have shown growth, leadership, kindness or perseverance throughout the week to come back to class to eat lunch with me. The kids love this and enjoy telling me stories about their family and friends, things they like to do for fun, past experiences in other schools and more. This gives me a little extra time with my students to really understand where they come from and who they are.

Tell us about a favorite lesson to teach. Where did the idea come from?

During the month of February, my class celebrates Black History Month by learning about famous Black leaders, current and past. Each week we celebrate a different area of impact: political, musical, athletic, and civil rights activists. These are my absolute favorite lessons to teach. My students get so incredibly passionate and invested in the topics and the issues of segregation and discrimination. For each leader that we learn about, I ask my students to memorize three facts about the person so when they go home they remember why these leaders are still important today.

What object would you be helpless without during the school day?

I would be absolutely helpless without my handy-dandy eraser. I keep one in my pocket at all times and one on my desk at all times and have a drawer full of them in case one gets lost or misplaced. These erasers get circulated around the room constantly. I believe that mistakes are proof that you are trying, but if you don’t take the time to fix those mistakes you will never learn from them.

What’s something happening in the community that affects what goes on inside your class?

It seems that the community at large has a misconception about learning disabilities and Individualized Education Plans, or IEPs. Many view the necessity of an IEP as a negative reflection of a student’s ability to succeed, whereas it is simply a plan designed to ensure that students who would benefit most from a modified and thoughtfully considered approach receive as much. In a world where, according to the National Center for Education Statistics, 14% or 7 million public school students have an IEP, it’s discouraging that more students aren’t provided the adequate services they need to be successful in the classroom. I have seen too many students who want so badly to learn and care about their education but fall short simply because they have not been afforded the necessary accommodations.

Tell us about a memorable time — good or bad — when contact with a student’s family changed your perspective or approach.

In the beginning of the school year, after we had finished our preliminary school-wide testing, I held conferences with a majority of my students’ parents to show them the results of the test and communicate to them how their child was doing so far in first grade. There was one student in particular that I was very concerned about based off of his test scores and behaviors in class. I asked the parent if we could start tutoring once a week. She agreed, and for the next two weeks, the boy stayed after school to work on things like letter sounds, letter recognition, and math skills. Then he stopped showing up to tutoring. Progress reports came out and his grades were still not where I had hoped. The student’s mother’s concern took the form of frustration and blame. Unfortunately, I was caught in the crossfire of the frustration. I asked myself what I could have done differently to help prevent this mother’s frustration? What did I need to change in order to avoid a similar situation happening again, as well as repair my relationship with this student and his family?

From this experience, I learned that no matter what my actions may be I need to explicitly state to each and every family in my classroom that I care about their child. I will do everything I can to help my students succeed but most importantly I need to express to the parent I am on their side. We are teammates in this fight for educational equity.

What was your biggest misconception that you initially brought to teaching?

Something we talked a lot about during summer training at Teach For America was being “day one” ready — meaning you have things like clear expectations, procedures, incentives, and consequences.I learned that despite the unknowns and hiccups that come with teaching, if you care about your students and commit to always learning and trying to improve, that is all you need to be “day one” ready. I had a belief that teachers must never make mistakes, but I realized that’s not true. If we expect our kids to grow and learn from their mistakes then we, as teachers, should expect the same from ourselves.

What are you reading for enjoyment?

Currently, I am reading a book called “Crazy Love” by Francis Chan. My friend loaned it to me describing it as a great book to analyze and understand your relationship with God. I do not think I could have survived this past year of teaching if I did not have a relationship with God. His love has given me the strength I need to fight for what is morally and ethically right each and every day in my classroom and school.

What’s the best advice you’ve received about teaching?

“It is easier to build strong children than to repair broken men.” This is a saying that I’ve discussed at length with my Teach For America cohort. For me, strength is rooted in confidence. I want my students to know without a doubt they can do anything they want when they put their mind to it. As a class, we build confidence by high-fiving each other for trying our best, cheering each other on when we see success and, of course, we have our “class-secret.” Our class secret, which we don’t want any other class to find out, is “We are the smartest first-grade class, not just in our school, but in the world and no one can stop us.” The best thing about this secret is that it is true. My students are the smartest and nothing will stop them.