Science, robotics, and technology are subjects that typically scare many teachers — and a lot of other people, too.

But a two-day robotics training program at the University of Memphis is trying to show teachers that, really, leading students in those subjects isn’t so difficult.

“We’re here today to let teachers know that robotics is not hard and it’s not hard to get kids interested,” said Johnathan Gales, a senior electrical engineering major at the University of Memphis. He was one of five undergraduate students who helped lead the teacher training sessions.

This is Gales’ fourth consecutive year as a STEM ambassador. The university pays students like him, an electrical engineering major, to go to local schools and show young people how to master practical technological skills, like designing robots or operating a 3D printer. STEM is a widely used acronym to describe fields in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics.

“The hardest thing is getting teachers comfortable with the idea that they don’t have to be robotics experts,” Gales said. “Robotics is about learning. … Kids are really creative and they’re much smarter than we were. The kids will end up teaching you something.”

Helping K-12 teachers overcome the perceived difficulty of understanding robotics helped guide the spirit of the free training program, which was facilitated by the West Tennessee STEM Hub, a collaborative initiative funded by a federal grant. The actual training, which attracted 45 teachers, was paid for by a $20,000 grant from the Tennessee Valley Robotics Foundation and another nonprofit known as Bicentennial Volunteers Incorporated.

The program takes Tennessee — and the nation — one step closer to producing professionals capable of meeting the rising demand for science and robotics specialists. These occupations and those in related fields make up the fifth-fastest growing job sector in the South and are projected to employ 2.6 million workers by next year, according to a report from the Tennessee Department of Education.

In 2014, Tennessee ratcheted up efforts to fill those jobs, developing a strategic plan for science education, which has focused efforts on giving students across the state access and exposure to related disciplines.

Gales is a product of the state’s push to encourage more students to pick science careers. He learned problem-solving techniques in a STEM academy during high school that drew him into the ambassadors program and engineering, and his ultimate goal of becoming a cardiologist. “They exposed us to any and everything,” Gales said of the extracurricular program that landed him multiple high school internships.

“When I came to college I knew I definitely wanted to stay with STEM and work with students,” he said, characterizing the ambassadors program as “the best of both worlds.”

Gales is now part of the engineering program at the University of Memphis. As a result of aggressive recruitment efforts, enrollment has increased some 30 percent over the past five years, according to data from the American Society of Engineering Educators.

At the teacher training, Gales’ education came full circle. It was finally his turn to stand at the front of the college classroom, explaining to teachers how to write code with confidence and make their robots stop and go on command.

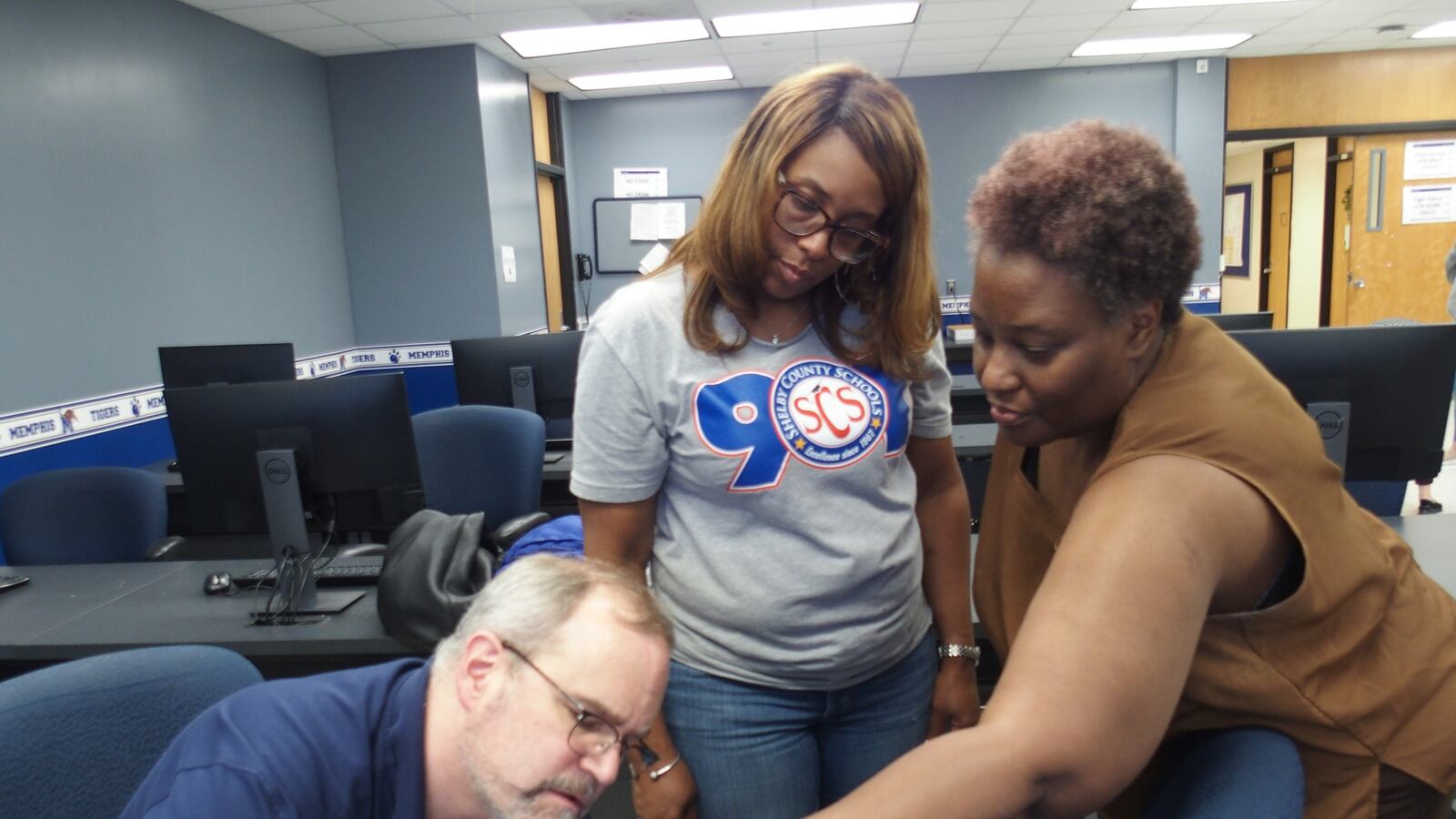

In another group, science teacher Iris Myers spent the afternoon troubleshooting her robot.

“We already have some of the resources, like robot kits, but figuring out what to do with them can be overwhelming,” said Myers, who admitted she didn’t know much about robotics before the workshop. She plans to start a robotics team this year at Brewster Elementary in Memphis, where she works.

She’s already got some leads on how to make that happen, after spending the first half of the training learning about competitive grants to fund coding clubs and student robotics competitions.

Her vision for bringing robotics education to Brewster stretches into the distant future.

“I figure if we can get them interested in science in elementary school, they’ll be more interested in it as they enter middle school, high school, and college,” she said as she worked on reprogramming her robot.

“Somebody has to fill the … jobs we’re seeing more of now,” Myers said. “People are retiring, so if the kids haven’t been exposed to the skills to do them, those jobs will just sit there.”

The robotics training allowed Myers and the other teachers to test out the miniature robot made of gray Legos she had spent the previous hour programming.

Assistant professor of engineering Daniel Kohn was also there to help Myers and the other teachers navigate the four-wheeled robot through a wooden maze

“Robotics is the quintessential STEM activity,” said Kohn. “You learn the engineering cycle through experimentation. You see what went right and wrong and try it again.”

With one hour left in the training, Myers and the other teachers in her training cohort were still trying to get control of their robots.

But she said she’s “not giving up” because she’ll expect the same perseverance from her students when she heads back to the classroom this year.