Accusing Republicans of compromising the future of Tennessee’s 1 million students, Democratic lawmakers called Wednesday for $1.5 billion more for public schools and an overhaul of an education funding formula they called “fundamentally broken.”

The legislature’s minority party wants to boost teacher pay, increase the number of nurses and social workers in schools, and improve student-to-staff ratios.

Its leaders also slammed Gov. Bill Lee and the Republican-controlled legislature for passing policies such as vouchers and virtual schools that shift taxpayer money to private schools and for-profit companies — at a time when many public school teachers are taking second jobs to make ends meet and digging into their own wallets to buy supplies for their students.

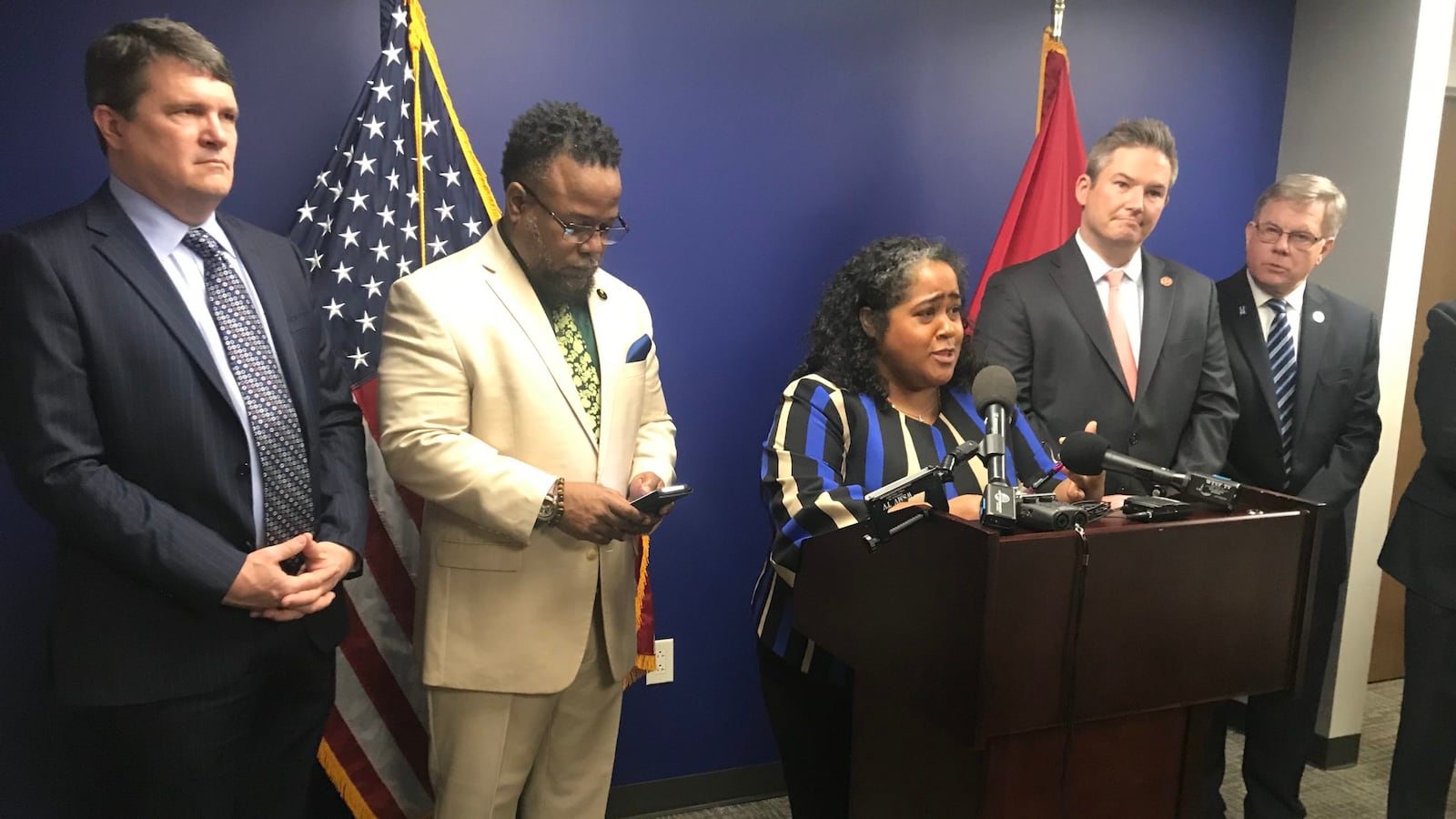

“We’ve heard the governor talk about this notion that Tennessee schools are fully funded. That’s just not true, as everybody who is in our schools knows,” said Rep. Mike Stewart of Nashville, who chairs the Democratic caucus, during a news conference.

The call to action comes as the Republican governor prepares to unveil his proposed budget and lay out the administration’s priorities in his second State of the State Address on Feb. 3.

It also coincides with another year of surplus tax collections in Tennessee, data ranking the state 45th in per-pupil spending, and test results suggesting that student achievement has hit a plateau.

“At a time when this notion of full funding is bandied about, our commissioner of education is admitting that we’re not making progress, that our scores our flat,” Stewart said.

Later on Wednesday, Lee promised that public education will be featured prominently in his upcoming spending plan. He specifically mentioned new investments in teachers, school leaders, literacy work, and early childhood education.

“You’ll be seeing that as we roll out our budget next week,” Lee told reporters. “In the State of the State Monday night, we’ll talk about why I’m deeply committed to public education.”

Tennessee currently spends about $6.5 billion on public education out of its $39 billion annual budget. That includes $1.5 billion added in the eight years under former Gov. Bill Haslam and a $370 million boost for teacher pay since 2016.

Even so, Tennessee’s investment of $9,225 per student trails most states in the South and its level of school funding remains the elephant in the room for state government. A trial is expected this year in a 5-year-old lawsuit filed by school districts in Memphis and Nashville over the adequacy of state funding for students and schools. If successful, the case could mean sweeping changes for how much Tennessee spends on K-12 education.

Central to that case is the Basic Education Program, or BEP, the funding formula that most everyone seems to hate but no one has been able to fix.

Senate Minority Leader Jeff Yarbro called it an “outdated formula that doesn’t reflect reality.”

“The BEP is a byzantine creation that almost no community in the state is happy with, and for good reason,” Yarbro said. “We have spent a lot of time talking about how to divide up the pie between small towns and bigger cities, between rural areas and suburban areas, when in reality there’s just not enough pie. The funding formula for the BEP is fundamentally broken.”

For instance, classroom size requirements have forced districts to hire more than 9,000 teachers beyond what the BEP provides to pay for their salaries, according to a recent analysis presented to the BEP Review Committee. That means local governments have had to pick up the tab for those positions, diverting city and county funds from other important needs like infrastructure.

“It’s important that we get this right,” said Sen. Raumesh Akbari of Memphis. “We’re saying as a House and Senate Democratic caucus, enough is enough. We cannot continue to exist in a fantasyland of sorts where we say that education is fully funding knowing completely well that it’s not. We cannot continue to support a broken formula to decide what money goes to our schools.”

In a 2018 interview with Chalkbeat before leaving office, Haslam talked about the challenges of trying to revamp the BEP.

“We came in and looked at turning it inside out in every way possible,” Haslam said. “But it was very difficult because, when you change it, you’re going to have winners and losers. You just are. And so the only way to change it is to do it like we did — add more money to the pie. If you’re just going to cut it up differently, it won’t work because the mad people will be madder than the happy people will be happy.”

Democrats are proposing revisions to the state’s funding formula, not starting over from scratch.

“The BEP Review Committee has recommended numerous changes that would actually update the law to reflect reality and what schools need. It is time that we do that,” Yarbro said.

Other legislation, he said, will seek to add $1.5 billion to the state’s budget for schools to offset a structural deficit under the BEP and ease the burden on local governments.

“That’s not getting us to the place of doing the most innovative work. That’s just getting us out of the basement of states from a school funding perspective,” said Yarbro, noting that only Mississippi spends less than Tennessee on education in the South.