When Education Commissioner Penny Schwinn unveiled her plan this month to use $1 million in federal funds to support “well-being checks” on Tennessee children, the goal was to make sure kids were safe, fed, and healthy, despite schooling disruptions created by the coronavirus pandemic.

Within days, Schwinn walked back her plan and apologized to state lawmakers dealing with public uproar about the prospect of families receiving phone calls, emails, or a knock at the door through a new government initiative. “Although well-intentioned,” she wrote on Aug. 14, “we have missed the mark on communication and providing clarity around our role in supporting at-risk students during an unprecedented time.”

The episode highlighted the challenges of supporting children outside of their school buildings, especially in a state that is intent on parental responsibility and wary of government intrusion. It also pointed to Schwinn’s pattern of rolling out initiatives and taking administrative shortcuts without ample legislative input, review, or approval, even as the former Texas academics chief is leading Tennessee through the biggest education upheaval in modern history.

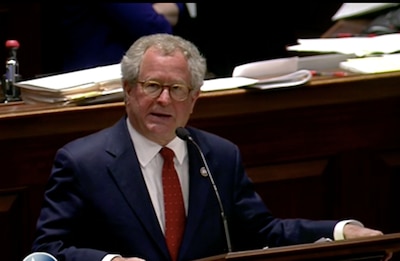

“I sincerely believe that the commissioner’s intention was good because kids have not been in school and there are issues with hunger and mental illness and domestic abuse,” said House Education Committee Chairman Mark White, a Republican from Memphis. “But when things get out without much vetting, we in the General Assembly are the ones getting calls from parents, teachers, and superintendents.”

The resulting tension between the GOP-controlled legislature and Gov. Bill Lee’s administration could hurt Schwinn and the Republican governor’s chances of providing long-neglected social and emotional health support for students at a time when the pandemic has escalated anxiety and stress for families and school communities.

“Our legislature is conservative and wants to keep government small, but some agencies get exuberant about their ability to create programs out of nowhere,” said Rep. Martin Daniel, the Knoxville Republican who chairs the legislature’s powerful Government Operations Committee.

‘Whole child’

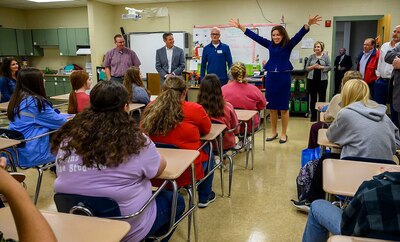

Schwinn pinpointed student mental health as a gaping hole in Tennessee education after Lee picked her in January 2019 as one of his most important hires. In a strategic plan unveiled last November, she made “whole child” education one of three priorities and envisioned using schools to expand mental health, wellness, and social services in Tennessee’s highest-risk schools.

But the coronavirus tanked tax revenues and the funding earmarked by the Lee administration to grow those resources. In June, Schwinn convened a 38-member child well-being task force, including four members of the legislature, to explore the challenges of extended school closures and galvanize communities “to check on our kids.”

The group produced a report, and the department created guidance for local leaders about conducting well-being checks on children from birth to age 18. Schwinn also announced that federal funding would be set aside to assist school districts and hire regional staff.

“There’s no Big Brother intent at all,” Schwinn told conservative Nashville talk show host Brian Wilson one day after her announcement created a firestorm on social media. “This is really about, ‘How do we support school-age children if they are not in school buildings?’ ”

Schwinn declined to speak this week with Chalkbeat, but her chief of staff, Chelsea Crawford, said Thursday that the well-being “toolkit” was an optional resource to guide local decision-making. She said the department is “going back to the drawing board” on how to help vulnerable students.

Meanwhile, Daniel said the Government Operations Committee has yet to receive an explanation from Schwinn saying under what authority she was acting to create what amounted to a new state program. She was scheduled to appear this week before the panel but was pulled from the agenda when Lee’s office intervened. Schwinn is now expected to testify in late September before the House Education Committee.

It wasn’t Schwinn’s first reprieve from answering lawmakers’ questions.

In February, a House subcommittee responsible for overseeing the spending of taxpayer money blasted Schwinn’s department for awarding a no-bid contract for $1.25 million a year to manage a new school voucher program that has since been put on hold. The award, for twice the budgeted amount, also bypassed the legislature’s fiscal review subcommittee. Chairman Matthew Hill, a Republican from Jonesborough, ordered Schwinn to appear with documentation showing exactly how the department decided on the award, but the governor’s office talked him down and no public hearing occurred.

A month later, members of the Senate Education Committee grilled Schwinn during back-to-back meetings about the department’s relationships with several private companies over recent textbook adoptions that prompted a lawsuit by one publisher. They also had questions about discussions with vendors over millions of dollars’ worth of anticipated contracts under a major literacy proposal that the legislature hadn’t approved. Lawmakers dropped a third round of questions when they abruptly recessed in March as the pandemic reached Tennessee.

“The whole COVID thing got us off track with addressing a pattern under Commissioner Schwinn,” said Rep. Scott Cepicky, a Republican from Maury County and a member of the House Education Committee, which had similar concerns. “I think there’s a general sense that this commissioner does what this commissioner wants and is not consulting those who have been elected by the people of Tennessee to be their voice on education policy.”

Big job

Schwinn was named to Lee’s cabinet just days before his inauguration. She had started her career in a Baltimore classroom with Teach for America and founded a charter school in her hometown of Sacramento, California, where she still serves on the board of directors. She later had brief leadership stints with education departments in Delaware and Texas, the latter of which included a controversial no-bid $4.4 million special education contract award in which an audit found Schwinn failed to follow state policies.

Lee has stood by Schwinn from the outset, even as she raised eyebrows with her very first policy initiative, which failed. Last summer, she proposed quick changes to Tennessee’s pioneering model for holding its schools accountable, then retreated after the chairs of the legislature’s two education committees told her to slow down and engage more stakeholders.

Her department also has had a revolving door, with more than 250 departures — mostly from resignations — in the first nine months of her tenure. That 19% departure rate exceeded those of her two predecessors over comparable periods. (The department has not provided updated turnover numbers as of this year, despite Chalkbeat’s multiple requests since February for that information.)

White said the turnover has hurt Schwinn’s ability to work with the legislature.

“When you lose a lot of institutional knowledge and experience, you don’t have the staff there to give you the background that you need and things get out without a lot of vetting,” White said. “I think that’s what happened with this child well-being plan. It wasn’t workable. It added more layers of government when we have two other departments who handle those responsibilities.”

Rep. Vincent Dixie, a Nashville Democrat and freshman lawmaker, has a different perspective after two years of serving on the House Education Committee.

“I think Commissioner Schwinn is stuck in a hard place,” Dixie said. “Gov. Lee has not provided clear direction and leadership during the pandemic, and the commissioner has had to make decisions that she’s not communicated clearly with the legislature. I think that’s caused a lot of confusion, miscommunication, and mistrust, but ultimately it all starts at the top.”

One upshot: Lawmakers’ confidence in the education department has deteriorated, and they’re increasingly leaning on the Tennessee State Board of Education, an 11-member body of appointed citizens that works with staff led by Executive Director Sara Morrison. Because of the emerging public health crisis and its impact on schools, the legislature voted last March to give the board emergency authority to address policy questions that crop up while lawmakers are recessed.

Digging in

Asked about legislative discontent with Schwinn’s leadership, the governor’s office pointed to a four-page list of partnerships and resources provided by the education department to support students, educators, and districts during the pandemic.

“Commissioner Schwinn is leading the department through an unprecedented crisis and the most challenging school year in the history of our state,” said Gillum Ferguson, Lee’s press secretary, adding that Schwinn is equipped for the challenge.

She also has earned points with superintendents for frequent communication since COVID-19 arrived. Three times a week, Schwinn holds statewide conference calls to discuss everything from federal relief funding to waiver requests to questions about staffing and data sharing during the public health emergency.

“This kind of communication and opportunity to provide feedback is extremely important for superintendents and something we have appreciated from the Commissioner during these challenging times,” said Sara Bunch, spokeswoman for the Tennessee Organization of School Superintendents.

Cepicky wants that same commitment to communication and collaboration with the General Assembly.

“I think a clearing of the air is in order,” he said about meetings set for Sept. 22-23 by the House Education Committee.

Sen. Dolores Gresham, retiring chairwoman of the Senate Education Committee after 12 years at the helm, said she also wants answers after fielding numerous calls and emails from concerned constituents. She’s calling for the commissioner to testify before lawmakers this fall.

“I support the House Education Committee and other legislators’ efforts to get further details or to investigate some of these concerns,” Gresham said.