After delaying the start of school by three weeks and pivoting to virtual-only learning amid COVID-19 concerns, Shelby County Schools began the new academic year Monday entirely online.

“This is historic,” Superintendent Joris Ray told reporters Monday morning after schools reopened virtually. “We have transitioned our children to the 21st century into virtual learning. This is big for our city; this is big for our state.”

For years, Shelby County Schools had discussed how to get all 95,000 students learning online. The district had already started online learning at a handful of schools, but had planned to phase in giving individual devices to all students by 2025.

On Monday, that happened years ahead of schedule. Students around the city logged in at 8 a.m. from their district-provided devices from their homes or from dozens of virtual learning centers set up at churches and day care centers. All students will be learning remotely until further notice.

Iesha Wooten converted one of her North Memphis bedrooms into a classroom for her three sons and her sister’s three children. She spent about $45 at the dollar store and an educational supply store to decorate the wall with inspirational messages and an alphabet letter chart with flash cards.

All six children were in their seats by 7:55 a.m., separated by folded cardboard privacy shields. Donning a yardstick, Wooten led the children in the Lord’s Prayer and had them repeat her motto for however long they will be using the makeshift classroom: “I can, I will stay focused.”

Each child was logged on to their first class by 8:20 a.m. as some teachers were delayed. Her middle son is supposed to receive speech therapy, but the sessions haven’t been scheduled yet. Most of the classes were dedicated to reviewing how to use the videoconferencing platform and establishing expectations for virtual learning.

“I know they are tired of being in the house, so when they decided to go virtual, I said I’ve got to do something different to spice it up,” she said. “I want to make it feel like they were actually in the classroom.”

But with the steady flow of questions, attempts to recapture drifting attention, difficulty switching to new classes, and rotating seats when laptop batteries died several times during the day, Wooten was quickly exhausted.

“It gave me a headache,” Wooten said after the first day of classes ended. But since one of her sons has asthma and another has sickle cell disease, which makes them more susceptible to severe symptoms from the coronavirus, she said she would rather have them at home than at school right now.

At the same time Wooten was supervising class, about 20 students logged in from their tablets and laptops at the YMCA’s Cordova headquarters. A large conference room with multiple tables and cardboard privacy shields at each station served as an overflow site for children of essential workers who can attend day care for free.

A week ago, the Cordova area had a waiting list of 250 students whose parents sought supervision for their school-age children while they work and their children attend school remotely, said YMCA chief operating officer Brian McLaughlin.

As classes resumed Monday, YMCA facilitators walked around the room, offering assistance to the students. “Pull your mask up, baby,” one kindly reminded a little boy who had slid down in his chair, his backpacked tucked under his chair.

Spotting a girl rubbing her arms a few minutes later, she inquired, “What’s wrong, baby? You’re cold?” The girl nodded. “I’m sorry, baby,” she said.

Across the room, two facilitators had located computer chargers for two students whose laptops had died three hours into the school day. “Don’t forget to charge your laptop at night,” a facilitator implored.

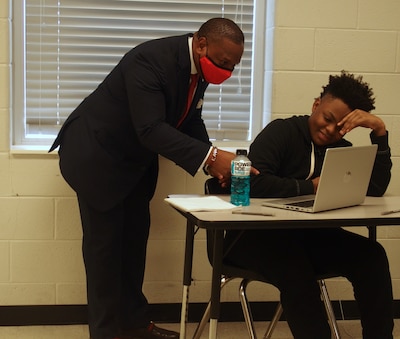

On the other side of town, students logged in from small classrooms inside the Memphis Athletic Ministries Grizzlies Center in the Alcy-Ball community. The nonprofit, which has long provided after-school care and student programming, shifted gears to provide care and support for students during the school day. The center shifted staffing hours from 3 to 8 p.m. to 8 a.m. to 3 p.m.

As he stood in the large gymnasium that is the centerpiece of the center, Jonathan Torres, vice president and chief operations officer, reflected on how much has changed because of the pandemic.

“Before we would have had 200 kids in here,” he said. “Now [because of social distancing requirements and internet bandwidth limitations in the facility], we have have 40 and it feels like you need to whisper.”

By mid-morning, district officials said there had been no major remote learning glitches or internet outages.

Computers and the internet have become essential for nearly every aspect of life, from banking to healthcare to education. But for many living in poverty, the lack of connectivity had made many of those things inaccessible. More than 60% of students in Shelby County Schools live in low-income families.

Last spring, the COVID-19 pandemic forced the closing of all school buildings in Memphis and around the country and highlighted the need for wider technology access. As a result, many school districts fast-tracked plans to provide one-to-one digital devices to students and offer more online educational opportunities.

The district is still distributing digital devices, but Ray said 90% of students have theirs. On Sunday, parents waited in long lines to secure laptops and internet hotspots. Students in prekindergarten through second grade got tablets. Students in third through 12th grade got laptops.

By mid-morning Monday, 80% of students with devices had logged in to their classes, said Jerica Phillips, a spokeswoman for the district.

Ray had warned parents last week to expect early problems with online learning. This district held a couple of test runs where all students were instructed to log on simultaneously to test internet capacity ahead of the start of school.

Ray said that virtual instruction would continue until the community has experienced 14 days in which new cases increase by single digits. When Ray made the decision in July to start the school year all virtual, he said the daily triple-digit increase of virus cases at the time was a contributing factor.

“We’re going to continue to follow science. We’re going to continue to look at the data on a daily basis. Because you can see when you don’t — look at other school districts around us,” he said Monday, referring to examples where schools temporarily halted in-person learning when students and staff tested positive for COVID. “You can go west, you can go south, you can go east. Look at the data, look at what’s happened. We have over 200 plus schools. We don’t have the luxury of getting it wrong.”