A vinyl chair made to rock back for hours of video games seemed like a fitting choice for 14-year-old Jalan Clemmons as he crafted his work space for online classes. No one really knows how long all-virtual learning will last in Tennessee’s largest district in Memphis, so might as well get comfortable.

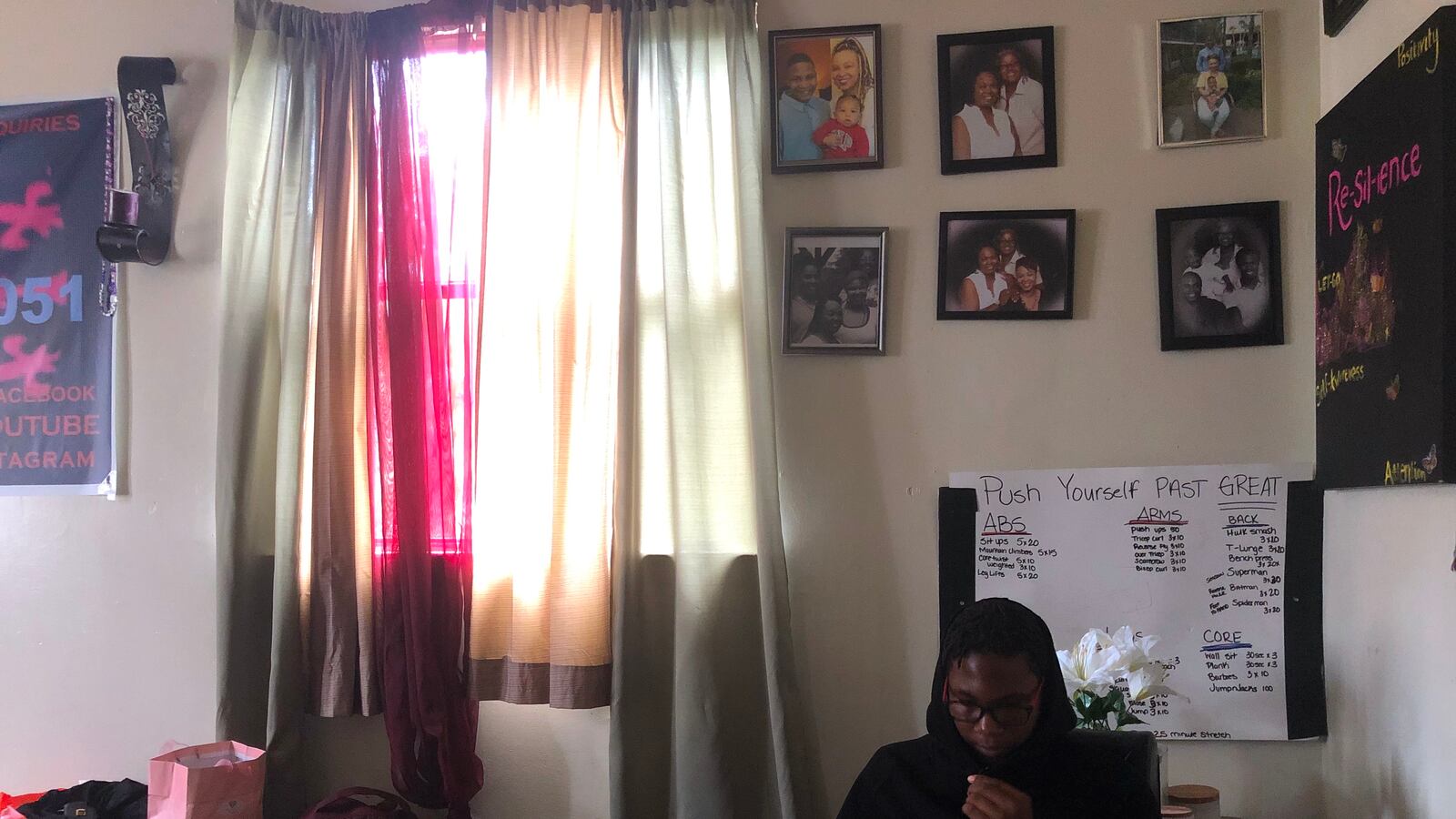

He grabbed a mat to go under the chair and a few pillows, and he plopped down in the corner of the apartment that his mom, Anna Nuby, usually uses for meditation.

Above him were photos of him with his mom and 2-year-old brother, Kobi, who didn’t understand why Jalan “going” to school meant he was still at home. Nearby, his mom had painted the word “resilience” on a frame, a project inspired by both pandemic-induced boredom and the theft of the family’s car in the spring.

After preparing his work space, Jalan powered up his district-issued laptop around 8 a.m. to join a video conference for his homeroom. But he chose to leave his camera off. He had attended a KIPP charter middle school with an entirely different set of classmates and didn’t know anyone at his new school.

In living rooms, kitchens, bedrooms, and daycare centers across Memphis, tens of thousands of students joined online classes for the first time in late August in a large-scale educational experiment district leaders said was necessitated by the continuing spread of the coronavirus.

This was a big shift for Shelby County Schools, which provided students with paper packets and televised lessons instead of the interactive virtual instruction seen in many large U.S. school districts when COVID-19 shuttered school buildings in the spring.

In making that decision, district leaders pointed to the city’s low share of households with internet access and said starting online classes without a comprehensive solution would exacerbate disadvantages for students in poor families. In many Memphis neighborhoods, fewer than 55% of households have the internet, according to U.S. Census data.

Over the summer, Shelby County Schools spent most of its federal coronavirus relief money on new laptops, tablets, and internet hotspots to make sure each of the district’s 95,000 students could attend online classes. So far, attendance rates districtwide have hovered around 90%, which is higher than districts in Denver, Chicago, and Detroit. Still, almost 3,000 Memphis students have yet to log on to a class or pick up a laptop three weeks into the academic year.

For Jalan, that day settling into his cozy work space was his first day of ninth grade at Hamilton High School, named after the first principal of one of the city’s first schools for Black students and backed by an active and proud alumni base.

Before the pandemic, he had hoped to join Hamilton’s dance team to get to know other students and work toward his dream of becoming a dance instructor. But the district is holding off on extracurricular activities that warrant in-person meetings. Joining the first class with only his initials showing on the screen took the edge off.

The trouble started when he tried to get into his second period class and got an error message.

He remembered from the virtual student orientation there was a one-stop shop for live technical help through a group video chat.

When he got there, he counted about 50 other students waiting for help — with no adult for nearly an hour. An administrator helped him locate his missing history class the next day. Chalkbeat contacted Shelby County Schools and the principal for comment, but did not receive any.

It was the latest in a string of confusing events for Jalan and his mom as they tried to gear up for the school year.

Before school started, Nuby had lots of questions she wanted to ask: Is there a hotline for technical help if they need it? How long will students have to do all-virtual classes? Do parents need to be in attendance for the online classes too? Are they really going to sit in front of a computer for seven hours every day?

She knew of two main opportunities to get answers before school started: the district’s laptop distribution and a virtual orientation.

Since she didn’t have a car to get the laptop, Nuby called up a distant cousin for a ride, the only relative she has in Memphis. She doesn’t know him well, but he often helps out if she needs something for the kids. She runs a T-shirt and graphics business from her living room and also has a video blog on health, beauty, and Black love.

The process for picking up the laptop lasted about an hour and a half. She briefly met Jalan’s principal. He gave her two sheets of paper before they had to drive off to keep the line moving: a general startup guide for the laptop, with the technical support hotline, and information about how to access the virtual parent orientation and other announcements.

“There was no way they were going to let you stop and get answers,” Nuby said. “I feel like I’m still on the edge about it ... We’re in this gray area where this is new and no one really knows how this is going to go.”

She was hardly alone in her questions. During the first week of school, the district received about 21,000 calls from parents. The district reported an average wait time of about 17 minutes on the first day of school, though some parents said they waited more than an hour. Nuby also tried to ask questions during the parent orientation the week before school, but her questions weren’t covered in the presentation. Afterward, staff members said someone would reach out to her. They haven’t yet.

Nuby is willing to try out virtual school for the first grading period before looking for other options. But she’s worried that Jalan won’t thrive in this environment. She’s constantly wondering what else she could do as a parent to put him ahead. She’s also worried the constant screen time will undo her years of trying to limit it.

“He’s 14. All his life I’ve told him, ‘Get off the TV. Get off the computers. You’re spending too much time in front of a screen. It’s bad for your eyes.’ And now our schools are mandatorily telling them they have to sit there,” she said.

Back in the corner of the living room, Jalan started math class right after lunch. His co-teachers told the class of about 10 attendees three times to turn on their cameras while laying out the rules of virtual learning. About 20 students were missing.

“I need to see that there are people on the other side of the screen, otherwise I might just be talking to nobody,” the first teacher said. “It helps us know that you’re engaged, it helps us know that you’re working, and it lets us know that you’re present, which will be very important when it comes to grading.”

He then paused class for about 20 seconds to see who would follow the instruction. Jalan did, and he spotted one other student’s face.

“Please be aware that we will contact parents if you do not comply,” the co-teacher warned. “Please turn your cameras on because everything we do in [Microsoft] Teams is recorded, so your parents will know what’s going on with you not participating.”

“This should not become an issue,” the first teacher added before moving on to explain other video conferencing functions.

District rules say it’s up to each teacher to decide if they will require students to turn on their video cameras during class. It took a few hours, but Jalan, a self-described introvert, kept telling himself he didn’t need to be afraid.

“Don’t be shy. Be yourself. And don’t be shy to show yourself,” he said he wants other students to know. “There’s no one at school who is going to hurt you.”

By the end of the week, his classes were going more smoothly, he said.

“It was OK for being virtual,” he said. “It was exciting sometimes and exhausting other times.”

Jalan usually has a break between classes to stretch and look at something other than his screen, a pleasant surprise considering how full his schedule looked on paper. Near the end of his first day, his 2-year-old brother ran into the living room, checking again to see if Jalan was still in his corner on the laptop. His mother planned her day around making sure Kobi wouldn’t disturb Jalan during his classes. But this time, Jalan’s class was over and he had a 15-minute break.

“JJ’s class is done. You can give him a hug now,” his mother told Kobi as he ran over to his brother. Jalan wrestled and chased Kobi around the room for most of his break before returning to his screen, where he turned on the video for his next class.