This story is a collaboration between Chalkbeat and The Commercial Appeal.

Seeking a new way to boost students’ reading skills at a crucial time, Shelby County Schools officials are betting big on a different kind of program that has shown positive initial results but lacks a long-term track record.

The Memphis district has proposed spending $14.5 million over five years on a leadership and teacher training company called Educational Epiphany, the brainchild of a consultant named Donyall Dickey whose work has already been piloted in the 88,000-student district.

The school board is scheduled to vote on the contract Tuesday, and the outcome is uncertain. Superintendent Joris Ray has been a vocal champion of Dickey’s work, but some school board members and educators have questioned the investment and the program’s philosophies.

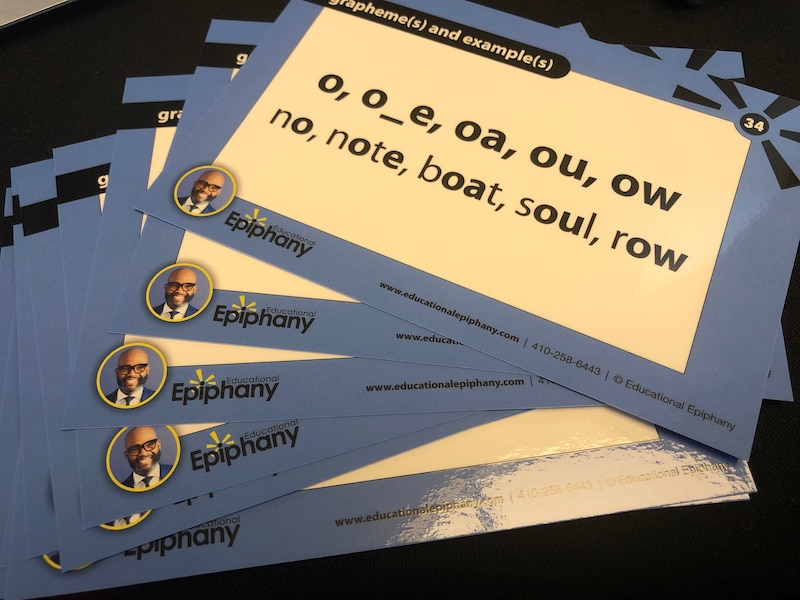

The contract would include teacher training and provide take-home literacy flashcards for students. In the first year, the district would spend about $5.6 million. The district then would have the option to spend $9 million more over the next four years if student test scores improve in the first year.

The program seeks to simplify what district leaders expect from teachers and help students break down words and understand their meaning. Most Memphis students are not meeting state requirements for reading.

The district briefly applied these teaching methods to seven Memphis schools in 2017 and since then has paid more than $1 million to Dickey’s company for teacher training.

District leaders have been striving to accelerate students’ reading skills for years, but have had limited success in a city where most students live in poverty. Improving reading has been even harder during the pandemic. Students have been learning remotely because the coronavirus has ravaged the community.

The district is depending on Dickey’s program to be a key driver in Memphis schools to meet state requirements for student reading levels. The most recent state test scores showed about 23% of third graders met that standard, compared with 36% statewide. District officials want 90% of third graders to be reading at grade level by the 2024-25 school year.

It’s too early to know what kind of impact this year’s training might have because students haven’t taken annual state exams yet. Even then, the unusual nature of this pandemic-disrupted year will make evaluation difficult.

Ray told board members during a fall planning meeting that he was convinced Dickey’s methods would propel more students to read on grade level.

“We’re going to do it one way,” he said. “And we’re going to do it in a way where we bring teachers along with us so teachers don’t feel like we’re doing something to them instead of doing something for them.”

Educational Epiphany in the classroom

The district spent $650,000 for Educational Epiphany to train teachers, principals, and other academic staff last summer and fall.

Teachers said that previously they had struggled to understand the district’s swarm of expectations on how they should improve student reading. So for some, the guidance in the new program is simple and intuitive.

Educational Epiphany instructs teachers to write out the objective, or what students should know by the end of the lesson. When reading the objective out loud, teachers help break down the words students may not know. Examples of words and concepts are offered by the teacher. Then the entire class is invited to participate in working through another example. Students get two other opportunities to work on examples, in a small group, and then on their own.

By the end of this process, students should be able to demonstrate that skill through different types of writing, such as presenting an argument or using various sources to explain something. In math, teachers should provide tangible ways for students to see how to apply complex math concepts that they learn. And after the school day, parents can reinforce literacy skills at home using Educational Epiphany’s flashcards.

Before, Bianca Martinez, a second-year sixth grade English teacher at Colonial Middle School, said the district expected teachers to go through multiple objectives in a day.

“A lot of us have already been teaching this way, but I think we feel heard and validated now,” she said.

District leaders had previously used a pacing guide that ensured teachers across all schools were covering the same material. Many students switch schools midyear because of poverty and housing instability. Now, there’s less pressure to cover a lot of material at once and administrators encourage teachers to review what students aren’t understanding.

But other teachers say the emphasis on breaking down the objective takes away precious time from building up other skills students need to learn to read.

Emma Sisson, a fifth grade teacher at Brewster Elementary, recently spent about 15 minutes out of an hour-long lesson just on the objective and its vocabulary, which Dickey calls “academic language.” Because of that, she ran out of time that day to finish a Frederick Douglass speech.

Before Educational Epiphany’s training, she would have spent less than five minutes on the objective and spent more time building on what students already know about the topic. Research has shown that familiarity with whatever topic students are reading helps them become better readers.

“Even if they know how to analyze and find the main idea, they may come across a topic they’re unfamiliar with and it’s like reading another language,” said Sisson, a third-year teacher. “I’m not saying that’s not important. It’s things I would be doing with my students, but the focus doesn’t allow me to do other things.”

So Sisson was surprised to learn that top district leaders were holding up that lesson as a good example. Dickey called it “masterful, powerful, thorough.”

He acknowledged that the objective Sisson was teaching was a mouthful: “Students will be able to describe and identify historical events, scientific ideas or concepts, and technical procedures in order to describe the relationships or interactions between two or more historical events, scientific ideas or concepts, and technical procedures in a text.”

Sisson paused to define “historical” as concerning past events. Students stumbled over reading words aloud like “concepts” and “procedures,” but encouraged each other to push through.

“It is evident that the professional development in which we have been engaged since June, July has made it to the classroom,” Dickey said during the district’s broadcast to all teachers about best practices.

Laura Taylor, an assistant professor at Rhodes College in Memphis who researches early literacy, said the language used in Tennessee standards are not geared toward students. She questioned whether students need to understand the education jargon.

“It’s not that I think students can’t learn that, I absolutely think they can,” she said. “The issue is whether or not that will be useful in helping them learn the things that we and they want to learn.”

Dickey did not respond to questions submitted by Chalkbeat and The Commercial Appeal for this article.

Dickey stresses that teachers should reinforce literacy skills in every subject. That aligns with national Common Core standards, which Tennessee’s learning requirements are based on.

Candice Golden, a fifth grade teacher at Dunbar Elementary, said she has seen her students apply their reading skills in science and math lessons. She uses Educational Epiphany’s guide that she said includes standard definitions for words as well as root words, prefixes, and suffixes. During a recent lesson, she told students fossils were something that “existed.” What does that mean?

“The student was able to connect that it happened in the past because of ‘-ed,’” Golden said, explaining one of the word endings she’s been teaching her students.

Board members’ reviews are mixed

Board members are split on whether to move forward on the $5.6 million contract with Dickey. Some say his methods are the answer they’ve been waiting for, while others want more time to see how the practices play out before spending more money.

“Spending a little over $14 million for one company that we don’t necessarily have all of the proven data that this is working for our children and our teachers, I’m a little skeptical about it,” board member Sheleah Harris said during a recent meeting.

Board member Shante Avant said she was worried the district was buying materials from Educational Epiphany that they could get for free from the state under a recently announced $100 million reading initiative called Reading 360.

The state’s program, still in its early stages, includes stipends for educators who attend training sessions about teaching students to read. It also includes classroom kits similar to Educational Epiphany’s flashcards, said Angela Whitelaw, a deputy superintendent. But the state resources will only go toward early elementary teachers who attend the training, while Dickey’s materials will be available to all students and teachers.

Educational Epiphany’s flashcards review common word endings and letter sounds. The cost equates to more than $40 per box based on the contract, and includes replacements, Whitelaw said.

“The Reading 360 resources alone will not be enough to address the longstanding literacy issues created by decades of underfunding by the state of Tennessee,” Whitelaw said in a statement.

Board member Althea Greene said Dickey’s program is worth the money because she’s seeing more principals and teachers agree on what is expected in classrooms — something she rarely saw in her career in Memphis schools.

“We’re going back to old practices,” said Greene, who with Harris are the only former teachers on the board. “We have a new generation of teachers who didn’t learn to read like I learned to read.”

Results in Memphis lack long-term track record

In 2017, Shelby County Schools tried Dickey’s program in nine pilot schools. Most of them were part of then-Superintendent Dorsey Hopson’s initiative that sought to improve schools at risk of closing.

The teaching methods were only implemented in the nine pilot schools in 2017-2018, Shelby County Schools officials said. Reading test scores increased at seven schools, ranging from 1 and 9.6 percentage points.

Whitelaw, the district’s deputy superintendent, said the primary change at the pilot schools was implementing Educational Epiphany’s guidance. Officials pointed to the one-year gains to justify expanding Dickey’s reach in the district. Ultimately, Dickey’s work did not continue in those schools due to inadequate funding, the district said. But the district continued to pay him for other services, including leading this school year’s earlier teacher training.

By 2019, the year after Dickey’s program ended, seven pilot schools posted improvements in test scores from 2017, the year before Dickey’s methods were adopted. Of those schools, three saw continuous improvements year after year. Because the pilot stopped after one year, it’s unclear how or if continuous gains were the result of Educational Epiphany teaching practices.

Taylor, the early literacy expert, cautioned against any school district looking to test scores during the pandemic to accurately evaluate a new program. She said that once students have returned face-to-face learning, existing diagnostic testing and state testing could measure effectiveness.

Teacher and student data are also important, she added, noting that talking to them is one way to measure how useful the program is.

Dickey has worked with other urban school districts, which have used state test scores to measure effectiveness. He started teaching in Baltimore in the late 1990s, rose through the ranks, and later led academic departments in Philadelphia and Atlanta.

When Dickey consulted two mostly Black elementary schools in Atlanta, state test data showed significant improvement in reading scores from 2016 to 2019.

But when Dickey began working with Baltimore schools as a consultant, the results were less clear. Shelby County Schools provided reading test scores from three Baltimore elementary schools that increased up to 30 percentage points in a single year, but didn’t specify when. Maryland state test data stretching back to 2003 did not match any of the numbers in the district’s report. Dickey did not respond to questions about the discrepancy.

Golden, the science and math teacher at Dunbar, said she has watched Shelby County Schools go through several teaching methods and would like to see consistency. To see if Dickey’s teaching practices work, the district would need to watch students over a few years, she said.

“When I think about delivery for the children,” she said, “I have to always think it’s a marathon and it’s not a race.”