Seven months into remote learning, Jalan Clemmons feels like most of his recent education has come from Google searches.

When classrooms in Memphis reopened last month, it worsened an already tenuous situation for Jalan, who like nearly three-quarters of middle and high school students in the district is still learning from home.

Before, with everyone remote, all students and teachers were on live video conferences. Now, even though everyone is still learning online regardless of whether they are at home or school, Jalan said teachers seem distracted by what’s going on in the classroom. They’re assigning more work for students to complete on their own. And there’s less live instruction.

“It’s way less interaction,” Jalan said. “They don’t even talk to us. It’s like we’re not even there.”

It wasn’t supposed to be this way.

Once teachers and some students returned to classrooms, Shelby County Schools’ plan called for classes to still be conducted through video calls so virtual students would have the same learning experience as their in-person peers.

Although there are times when in-classroom and remote students may be separated from each other, district leaders still expect most class time to involve everyone working together through video conferencing so teachers can see students working, said Antonio Burt, the district’s chief academic officer.

“We want a balance between synchronous and asynchronous instruction,” Burt said. “From a district perspective, we wouldn’t expect a change with some students in person and some virtual.”

Like a lot of students, Jalan has at times struggled with remote learning.

Four months into the school year at Hamilton High, he discovered he was missing more than 70 assignments, the result of technology issues and miscommunication with his teachers. It took two months, but he was able to catch up. Where he had been at risk of failing, now his most recent progress report shows As and Bs.

Some of the issues the 15-year-old has faced this school year might have been avoided if he had been in the school building with his teachers. Most high schools struggled with the abrupt pivot to remote learning last year, but Jalan and his mother, Anna Nuby, believe the challenges have been particularly acute at a neighborhood school like Hamilton High, where the graduation rate is nearly 20 percentage points lower than the district average.

These last years before Jalan becomes an adult are pivotal, she said. She wants him to be in a school where he can thrive.

“I’ve worked too damn hard to make sure we’re not in certain situations,” Nuby said.

As this unusual year nears its end, she wonders if after everything Jalan has been through, Hamilton High can ever be that place.

Until early March, Memphis school buildings were closed to students. But after state legislators threatened to cut funding to districts that did not offer at least 70 days of in-person instruction, Superintendent Joris Ray reluctantly ordered teachers to return to classrooms.

Still, virtual learning is the most popular option among Memphis parents in public schools, and their children already had made it more than half the school year online.

To give teachers time to prepare to return to classrooms, all students were given assignments to do on their own instead of logging into classes. For middle and high school students, that period of transition lasted two weeks.

Remote students were supposed to spend another two days doing online assignments to allow time for in-person students to adjust. District officials said those two days were “instrumental” in allowing teachers time to prepare. It was supposed to be temporary.

Then disorder set in.

Teachers reported that school internet connections shut down lessons multiple times a day. Some struggled to balance instructing students in classrooms and students online at the same time — a practice other districts around the country have employed to handle staffing challenges. Then, a fire damaged a fiber cable in South Memphis, knocking out the internet for several schools in the area for a day, district officials said.

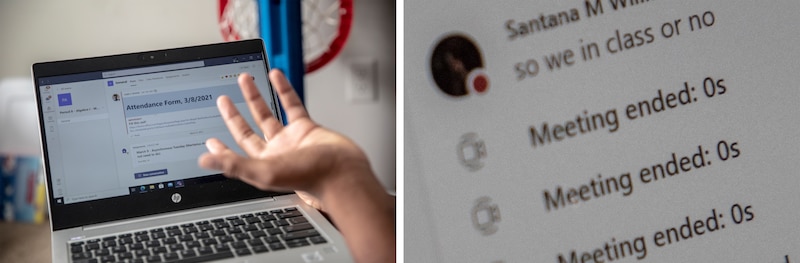

Another day, Microsoft Teams, the videoconferencing platform the district uses for all students whether they are in the school building or at home, crashed. Teachers reported more crashes after that, too.

Jolie Madihalli, president of the Memphis-Shelby County Education Association, said she got reports from teachers at a majority of schools that internet connections dropped suddenly and often as thousands of simultaneous video feeds strained the district’s system. Shelby County Schools officials acknowledged the internet issues and said they were working on them.

By the third week of reopening classrooms, Madihalli said the internet was more stable, but it was a stressful time for students and teachers. “It has a mind of its own,” she said of the internet connections.

The end result: For an extended period, students learning from home found themselves learning on their own at times and learning together with in-classroom students at times — and often, confused about what was supposed to be going on.

One day shortly after in-classroom learning resumed, Jalan watched as chaos played out on his laptop screen.

“We in class or no,” one student typed in an online chat.

“WHERE’S THE JOIN BUTTON,” typed another.

No response.

Usually, a link to join the next class pops up in the bottom corner of Jalan’s laptop screen. For days, he got nothing.

“So, I would just do my work and go on about my day,” he said.

When he came across new information that hadn’t been covered in class yet, he’d Google what he didn’t know.

The school district has taken steps to help ensure student learning wouldn’t suffer in the transition back to classrooms, said Burt, the district’s chief academic officer. District officials, for example, provided teachers with videos showing central office staff giving mock lessons to students in person and online through the videoconferencing platform, he said.

Teachers can put students in smaller groups to work together or allow for some class time for students to finish assignments. Teachers also should be giving students work later in the week that allows them to demonstrate what they’ve learned during class, Burt said, which may feel less interactive to students.

Still, district leaders expect most of class time to be all together.

After live classes restarted, Jalan said he felt more isolated than he had when everyone was learning remotely. At least when everyone was virtual, he said, his teachers noticed if he was there.

Advocates for reopening schools have argued that students, particularly ones in marginalized communities, would benefit from in-person learning. In some cases, school leaders have contacted parents of students who are struggling academically to try to convince them to send their children back.

In Shelby County Schools, officials say they have seen positive changes since some students returned last month. Students have submitted more assignments, and there have been “more positive teacher-student interactions,” the district said in a statement.

Much of the focus of the reopening debate has been on the youngest students and those with special needs. But ninth graders also are vulnerable, some experts say.

For ninth graders’ developing brains, the jump from middle school to high school workloads can be difficult without a lot of support, said Habib Bangura, the national director of analytics for Stand for Children’s Freshmen Success Network. As many teachers divide their attention between online and in-person classes, the risks are higher that a student will fall behind or get lost in the system.

“It just overwhelms their capacity to cope and their ability to manage,” Bangura said. The network Bangura is a part of coaches 20 Memphis high schools, including Jalan’s school, and 150 others nationwide on how to reduce the number of high school dropouts by focusing on freshmen.

Coaches in Memphis schools have encouraged teachers to help freshmen manage their time, organize their work, and juggle class assignments.

They also urge school leaders to pair students with an adult mentor in the school who will check on their progress periodically. It’s part of a larger effort called “check and connect,” backed by University of Minnesota research that showed students were less likely to drop out of high school when a mentor checked on them.

Bangura said seeing into students’ homes during virtual learning has given teachers a look at some of the “challenges that students face outside of school.” He believes it has made many educators more empathetic.

Jalan doesn’t have a mentor. Some of his teachers talk with him more than others. But he said he doesn’t feel like he has developed meaningful relationships with any school staff or classmates during remote learning.

Instead, he has looked for connections outside of school. He’s been meeting up with friends to practice Memphis Jookin, a dance that emphasizes footwork and tip-toe spinning. The group recently met on Beale Street, the city’s entertainment district, and received $45 from bystanders who watched them dance. One of Jalan’s recent videos got more than 2,400 views.

“It took all the stress away from school,” Jalan said. “It blew it all away.”

Before the pandemic, Jalan might have joined the dance team at Hamilton High, opening up possibilities of connection and friendship. But that didn’t work out. Jalan’s first high school experiences have largely been him in his living room staring at classmates through a laptop screen.

Hamilton High School was never Nuby’s first choice for Jalan. He attended a KIPP middle school in Memphis, but he didn’t get a spot at the charter network’s high school. He wound up at Hamilton, the nearest high school to their apartment.

After months of poor communication with her son’s teachers during virtual learning, Nuby thinks it may be time for Jalan to find a new school for the fall, a fresh start in some of the most important years of his education.

If she had a car, Nuby would have transferred Jalan to a different high school months ago.

Now that her rent, utilities, phone, and internet bills are paid up for the rest of the year because of her stimulus money, she plans to use the next federal relief check toward a car this month. Then, she can have more flexibility to find a new school.

Nuby knows what kind of school she wants: A place where Jalan can thrive, where teachers and administrators are determined to see students graduate and then attend college.

About 94% of students graduated on time last year at KIPP Memphis Collegiate High School, her first choice a year ago, compared to Hamilton High’s 61%, according to the Tennessee Department of Education.

She likes Middle College High, which was named a National Blue Ribbon School by the U.S. Department of Education in 2015. Students can take college classes at neighboring Christian Brothers University, and more than 95% of students graduated on time. And unlike other selective-admissions schools in Memphis, nearly all the students at Middle College High are Black.

Nuby knows that all schools in Memphis have likely had some challenges with remote learning — spotty internet connections and the challenge now of teaching online and in-person students simultaneously — but observing how some teachers interacted in virtual classes didn’t reassure her about the environment she would eventually send Jalan to in person at Hamilton High.

At one point in the year, Jalan desperately wanted to be in the classroom. He disagreed when his mother decided to keep him home. But now, he’s glad he didn’t go back.

He plans on focusing on turning in his work — and hoping for a new beginning for his sophomore year.