For months, Tennessee Republican lawmakers were hearing from dozens of parents concerned about how educators were trying to make their lessons more inclusive in response to the nation’s racial reckoning.

One mom even reported that her 7-year-old daughter, who is white, was having suicidal thoughts because of uncomfortable conversations about race in her classroom.

Simultaneously, GOP leaders were tracking bills that would restrict how race and racism are taught in other states. But they hadn’t planned to push their own version until the week of April 19, when President Joe Biden’s administration announced a new grant program for history and civics education.

The grant program — prioritizing instruction on diversity, anti-racism, and the legacy of slavery — unleashed a torrent of backroom discussions just 2½ weeks before Tennessee’s General Assembly adjourned on May 5.

Interviews conducted recently with key players in those discussions shed light on why Tennessee lawmakers abruptly moved to join their counterparts in Idaho, Iowa, and Oklahoma to ban the teaching of topics they viewed as cynical, divisive, and misguided.

The bill passed along partisan lines in Tennessee’s GOP-controlled legislature on the final day of the session, with white Republican legislators voting for it and Black and white Democrats voting against it. On Monday, Republican Gov. Bill Lee signed the legislation into law.

The new law restricts how public school teachers can talk about racism, sexism, and bias in their classrooms beginning next school year. But most educators were unaware of the 11th-hour proposal as it barreled through the legislature during Teacher Appreciation Week. They were focused instead on giving their students annual state tests and closing out a pandemic-challenged school year.

“We moved fast,” said House Education Committee Chairman Mark White of Memphis, who helped guide the bill’s passage.

“It was too important to wait until next year,” White added. “We want our teachers to know that, when the new school year begins, they should not teach certain concepts.”

Viral email stokes mistrust about socialist indoctrination in schools

In formal House discussions, Biden’s grant program was not highlighted as Democrats inquired several times about the impetus for the legislation.

Rep. John Ragan, the Republican sponsor from Oak Ridge near Knoxville, said divisive social concepts mirroring Marxist-style indoctrination were seeping into Tennessee classrooms. He cited statistics about lagging literacy rates and graduates who need remedial coursework and said “far too much classroom time is devoted to things that do not adequately teach our students reading, math, science and other essential academic skills.”

During discussions in committee and on the floor of the House, Ragan also read parts of an email forwarded to him about the 7-year-old student in Franklin, an affluent town south of Nashville in Williamson County.

The story circulated extensively on social media after an April 21 education forum sponsored by the Republican Party’s local chapter and covered by the Tennessee Star, a conservative news outlet. According to The Star, a woman identifying herself as the parent of a student at Liberty Elementary School said her daughter came home from school one day and told her, “I’m ashamed that I’m white.”

Ragan told lawmakers: “The daughter then asked her mother, ‘Is there something wrong with me? Why am I hated so much?’”

“The 7-year-old is now in therapy,” Ragan said. “She is depressed. She doesn’t want to go to school. ... She is scared to death and has even had thoughts of killing herself.”

Bobbie Patray, the long-time president of the Tennessee Eagle Forum, which lobbies on family issues and opposes critical race theory, said the story mobilized people in Williamson County and across Tennessee to call for stricter guardrails on what teachers are teaching.

“It lit the match,” Patray reflected later in an interview with Chalkbeat. “It’s fine to think about what goes on in New York or California or somewhere out there, but this story about a 7-year-old girl brought it home to parents who said, ‘That could have been my baby!’”

“A 7-year-old girl ought to be playing with doll babies,” she added.

David Snowden, superintendent of the Franklin Special School District, said no parent has come forward to Liberty Elementary Principal Amy Patton, her teachers, or district officials with that complaint.

“I’m baffled,” Snowden told Chalkbeat a month after the report was published. “Most people with issues come to us for help in resolving them. But we have heard nothing directly from a parent.”

Snowden said administrators took the report seriously, speaking with teachers and reviewing class rosters to try to pinpoint any student who might be upset, as well as lessons that could have been upsetting.

“We didn’t uncover anything,” he said. “I’m not saying it’s not real. Maybe the parent will come forward to talk with us after the school year ends.”

Ragan told Chalkbeat that he didn’t talk with the family but spoke with an “original source” and stands by the story. “I have no reason to doubt it,” he said.

About half of the 3,600 students in the Franklin district are white, a fourth are Hispanic, and 14% are Black. In the much larger neighboring district of Williamson County Schools, 80% of students are white, 6% are Hispanic, and 5% are Black.

Williamson County has been a hotbed of discussion about diversity training for teachers and learning materials that some parents have found inappropriate or offensive.

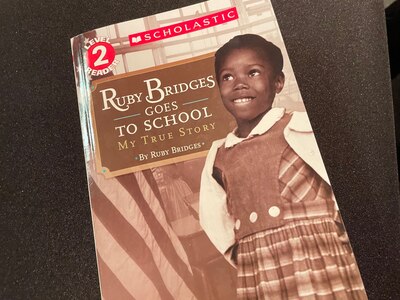

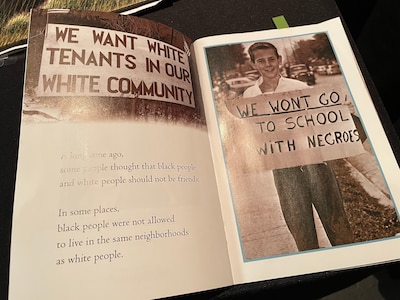

Nationally recognized curriculum called Wit & Wisdom, approved by both the state and the county district and introduced last fall, includes second-grade reading materials about civil rights champions like Martin Luther King Jr. and Ruby Bridges, the 6-year-old who became the first Black child to integrate an elementary school in the South.

Many parents viewed those as important stories but worried they were being presented in a way that was too graphic and deep for their children in early grades. Some believe the curriculum is part of a wider conspiracy to indoctrinate their children in socialist principles. The mistrust has mobilized groups like Moms for Liberty, which recently hosted a nearly three-hour presentation on critical race theory attended by 300-plus people in Franklin.

“The amount that we don’t know about our teachers who teach our children should scare us, with the amount of time and influence they have on our children,” Robby Starbuck, a Nashville-area father and filmmaker, told the crowd.

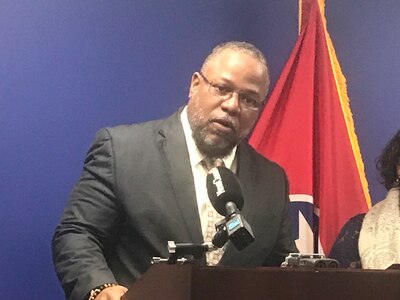

Sekou Franklin, an associate professor of political science at Middle Tennessee State University, said there’s a broader dynamic at play beyond curriculum concerns. The goal of Tennessee’s critical race theory bill, he said, was both to rally the Republican base for upcoming elections and anchor public education in a “white-washed” presentation of history and current events.

“This is really about white kids and what they’re learning in our K-12 schools,” Franklin said. “They’re seeking to insulate white kids from a narrative that could threaten the political and economic power of whites at a time when you have a growing non-white population.”

Biden civic grants ‘trigger’ GOP response

The new Tennessee law outlines 14 tenets that teachers cannot present or promote. The ideas generally mirror language in bills filed in recent months in Idaho, Iowa, Missouri, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, and West Virginia.

Among the forbidden concepts: that the United States is “fundamentally or irredeemably racist or sexist;” that an individual, by virtual of their race or sex, “bears responsibility” for past actions committed by other members of the same race or sex; and that a “meritocracy is inherently racist or sexist.”

“Our bill never mentions the words critical race theory,” said Rep. Scott Cepicky, a Republican from Maury County, also south of Nashville. “We focused on 14 tenets that are divisive in nature, pit one race or sex against another, and produce blame. That’s not what our country is about.”

In the week after the federal civics grant announcement, Cepicky and White met twice with other leaders of the House’s five education panels to discuss a potential legislative response to critical race theory, the academic framework that examines how policies and the law perpetuate systemic racism.

“Everybody knew what we were talking about because we had been following this issue. It was just like, ‘I think it’s time. What do y’all think?’ We all agreed it was time,” said Cepicky, calling the Biden grants “the trigger.”

On April 27, with just over a week before adjournment, White, Cepicky, and Ragan met with House Speaker Cameron Sexton in his office to ask for his support. Sexton conferred with Lt. Gov. Randy McNally, the speaker of the Senate, and they agreed to back a new proposal banning any teaching that injects race and sex when discussing legal, economic, educational, and other systems that GOP leaders believe are merit-based and colorblind.

But there were logistical challenges, since new bills couldn’t be introduced at that point in the session and education committees for both chambers had completed their business and closed for the year.

An existing bill by Ragan and Sen. Mike Bell, a Republican from Riceville, was chosen as the vehicle. Because it was a “clean-up” proposal to delete outdated language in state code, its general description was broad enough to add an amendment prohibiting the concepts that the GOP found worrisome. The bill had already passed in the Senate and was awaiting a vote on the House floor.

On the Friday afternoon of April 30 — three days before the body would adjourn — Ragan filed his amendment after White announced he would reopen his committee briefly to consider new business. But a hiccup emerged the following Monday morning when, an hour before the meeting, a staff member for Senate Education Committee Chairman Brian Kelsey asked to add three more tenets to the 11 already in the amendment.

White said no to more last-minute language, noting that the Senate eventually would get to vote on any amended bill.

Within 30 minutes and over the objections of the committee’s three Black Democratic members, the revised bill easily cleared the committee, while more than 60 Republican representatives signed on as co-sponsors.

The next day, after an hour of emotional debate, the House passed the measure too.

Later, Democrats thought they had dodged a bullet when the Senate quietly rejected the measure. But Kelsey, a lawyer from Germantown near Memphis, simply wanted it sent to a conference committee so he could add his three new tenets.

“There was no question we were going to pass the bill,” said Senate Majority Leader Jack Johnson of Franklin, about his chamber’s voice vote. “It was a procedural motion. We wanted to add provisions to make the bill a little clearer, a little more thorough.”

Two Democrats who serve on the education committee had a different perspective.

“This whole thing was orchestrated,” Rep. Antonio Parkinson, from Memphis, told Chalkbeat later. “The way it was done completely limited debate and the chance for citizens to offer their views. It was intentional.”

Rep. Vincent Dixie, from Nashville, called the rush to passage disheartening.

“If you are a person of color and you live in Tennessee,” he said, “you feel very diminished right now, that you don’t feel like you’re part of the conversation.”