When Tennessee and its largest school district launched separate school turnaround programs in Memphis in 2012, they adopted markedly different models but shared one similar philosophy: Recruit talented educators and get out of their way.

Turns out, that common approach didn’t work well for either the state-run Achievement School District or Shelby County Schools’ Innovation Zone, which also have produced mixed academic results that remain far below the state average.

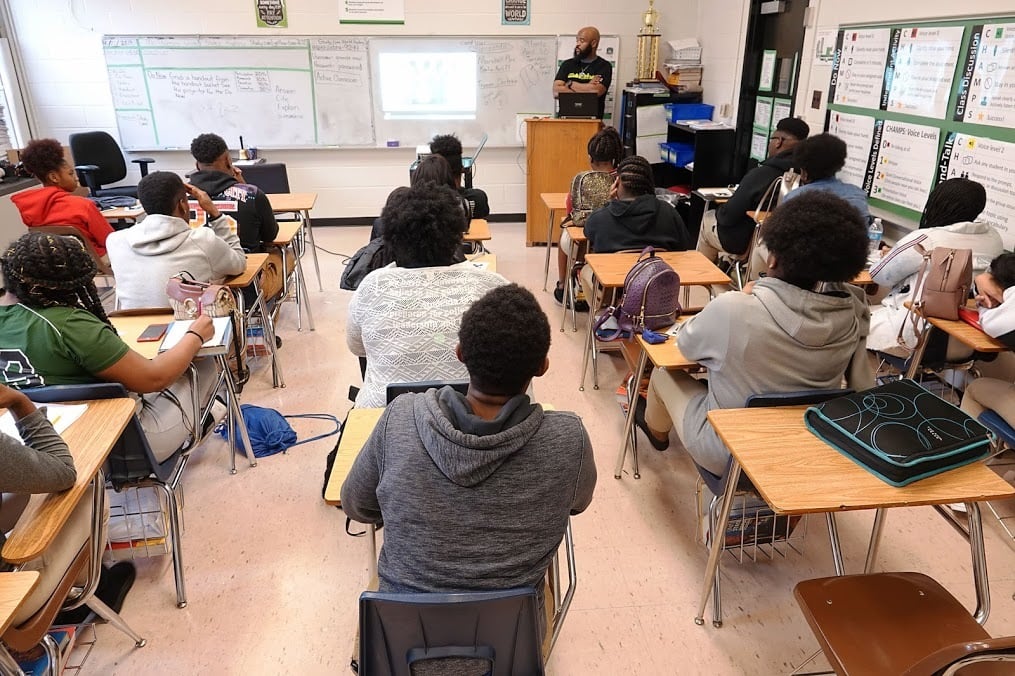

Not only were teachers and principals in both models working with students with extreme academic and social needs, but they also had to abide by Tennessee’s tougher new academic standards and a stringent accountability system that measured academic growth from year to year.

“For many teachers and leaders, autonomy actually meant isolation,” said Joshua Glazer, a researcher who introduced a two-day school turnaround conference that wrapped up Wednesday. “Autonomy went from being a really great idea to just a really bad idea as that strategy started to unravel.”

Limiting autonomy in an education setting with multiple challenges is one of the lessons learned in Memphis, a national hub of school turnaround work that has at times looked good, bad, and outright ugly. Other takeaways include the importance of giving families an early seat at the table when making changes and seeking more collaboration among state and local officials throughout the process.

Unlike incremental academic gains associated with school improvement, school turnaround calls for dramatic gains in a short period of time.

“Ultimately, this is heavy, hard heart work that won’t result in magical outcomes,” said Terence Patterson, CEO of the Memphis Education Fund, which convened the virtual conference to inform future school improvement work, as well as education strategies generally in a post-pandemic world.

Tennessee’s Achievement School District grew out of its federal Race to the Top award and initially gave itself five years to transform chronically underperforming schools taken over by the state. The so-called ASD had a lean central office and mostly assigned the schools to charter operators to do the work. But overall, the district has not improved student outcomes, has struggled to retain teachers, and failed to catapult schools out of Tennessee’s bottom 5% as promised.

With its heavy-handed takeover of neighborhood schools and broken promises on performance, the ASD also hasn’t endeared itself to a city with a highly charged racial history.

The Innovation Zone operates in Memphis under a more traditional district structure. Known as the iZone, the program launched through Shelby County Schools and gave their school leaders charter-like autonomy to choose their own curriculum, give bonuses to lure highly effective educators, or extend the school day. The iZone achieved stronger academic outcomes than the ASD in its early years but has struggled to maintain funding to do expensive turnaround work.

Glazer, an associate professor of education policy at George Washington University, described the two governance models as “apples and oranges” but noted they faced common challenges in Memphis and shared an early belief in talent-based autonomy. Within three years, however, both initiatives backed off their autonomy mindset and provided their educators with common curriculums, lesson plans, and instructional practices.

“Everybody’s got a plan until they get punched in the mouth,” said founding ASD superintendent Chris Barbic, quoting former professional boxing champ Mike Tyson.

For Barbic, that punch came 18 months in as he sat in a classroom and saw the ASD’s systems weren’t working.

“We still believed in autonomy, but the autonomy needed to live at the operator level, not at the school level. If we just give every school autonomy, you’re going to create the wild wild west,” he said.

Leaders of Shelby County Schools had a similar revelation.

“It sounds great, but it really needs to be sort of earned autonomy,” said Dorsey Hopson, a former superintendent who led Shelby County Schools during most of the iZone’s existence.

Hopson said educators need turnaround experience before gaining the freedom to innovate. In the meantime, they should lean on common tools and coaching, which foster collaboration and reduce burnout in a highly stressful environment.

“The burnout is real,” said Roderick Richmond, an architect of the iZone. “You’re not going to have educators who can do this 25 and 30 years the way people in the past used to,” partly because of the pressure to raise test scores quickly of students who are significantly behind.

Other takeaways are the importance of engaging authentically with the community that’s being served — and considering all of the pathways for achieving goals, even if it means slowing down the process and changing tactics.

“The way the ASD was set up, it had a lot more sticks than carrots,” Barbic said about wielding state authority vs. providing incentives.

While the state-run district was positioned to act quickly, Barbic acknowledged “we were probably too aggressive on the sticks and not thinking about what other options there were besides doing nothing, using charters, or running the schools ourselves.”

Richmond said local distrust and power struggles between the ASD and Shelby County Schools distracted from the overarching goal of equipping Memphis students for the future.

“If I had to do it all over again, I think the communities, the school board, and the state department probably should have sat down and agreed on a common set of goals,” he said. “Goals alignment helps you to truly collaborate around the work, and you can always defer back to goals whenever people go off on their own agenda.”

Most Memphis leaders credit the ASD for creating a sense of urgency to address underperforming schools that had languished for decades with inadequate resources and attention. But urgency has a double-edged sword when community voices are muffled, said Janet Thompson, a retired leader with Shelby County Schools.

“The cornerstones of our community are traditionally black high schools, which have been traumatized [by the ASD],” Thompson said, citing attendance, morale, and school climate, including athletics and the arts.

“I think we’re not better for it,” she added.

Barbic said quick structural changes to large government-run entities aren’t possible without making people angry. “That’s why most districts don’t do it,” he said. “They add programs instead.”

But he acknowledged that building grassroots support and collaborating with partners over time is ultimately more effective — an approach that has since shown promise in states like Massachusetts and Indiana, as well as Tennessee in Hamilton County.

“We’re in a world today where top-down just doesn’t work,” Barbic said. “Top-down can open a window, but it can’t sustain a window. You need on-the-ground support for a window to stay open.”

The ASD is at a crossroads as it oversees about 9,000 students in 25 schools in Memphis and two in Nashville. Under a transition plan the legislature approved in May, some schools will exit after being part of the state-run district for a decade.

Tennessee Education Commissioner Penny Schwinn also has said the ASD likely will be revamped and will remain the state’s most intensive intervention for its lowest-performing schools.

Now with 10,800 students in 23 schools, the iZone has shown more promise but remains “fragile,” according to the most recent report from researchers who cited shifts in leadership and state and federal policy.