Seeking a more holistic approach to discipline, Frayser Community Schools reduced the number of law enforcement officers in its schools this year.

The change was prompted by the nationwide dialogue on systemic racism following the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, two African Americans who were killed by white police officers. The charter network felt that it had a moral obligation to become a more equitable institution.

Under its anti-racism initiative, the Memphis charter school network removed officers from its two middle schools, Humes and Westside Middle Schools, keeping one private officer in its high school, M.L.K. College Preparatory High School.

“School is the greatest institution that we have. Everyone in America has to attend school,” said Bobby White, CEO of the organization. “So if you recognize that racism is so American, that our institutions are inherently racist, then you recognize that how schools are run are going to mimic what happens in the criminal justice system and in other areas of life.”

White added that Frayser Community Schools are working to change the culture.

A recent report from the Brookings Institute shows that adding police to schools criminalizes typical adolescent behavior. For example, police involvement can escalate graffiti on the bathroom walls to a vandalism charge, cutting class to a truancy charge, or vulgar language or an outburst to a disorderly conduct charge.

Black and Hispanic students have the greatest risk of being exposed to the long term consequences of officers in schools, including higher rates of arrests, expulsions, and suspensions. The missed class time contributes to the higher dropout rates and lower college enrollment rates for Black and Hispanic teenagers. These effects are particularly troubling for Memphis because more than two-thirds of Shelby County Schools students are Black.

Over the summer, Frayser teachers received professional development training to help prepare them for the shift away from policing.

The charter network also implemented a “no expulsions” policy in all of its schools. Instead of expulsions, students will meet with counselors and three new restorative justice specialists. In addition to an existing social worker in the high school, the district also has hired an extra social worker to be shared between the two middle schools.

Instead of suspending or expelling a child when they have a minor offense like talking back to a teacher or cutting class, specialists will sit down in a restorative circle with students, family members, teachers, and whoever else was involved to get to the root of the issue that spurred the behavior.

After that, the student will “right the wrong” under the supervision of the specialist. For example, if a student was caught vandalizing a bathroom stall, they would be asked to remove the markings.

“We wanted to do something different,” White said. “It pulls in our innovative and thoughtful approach to our disciplinary practices, as well as how we view trauma inside of our schools, given that our babies start off with racism being trauma within itself, on top of all of the other things that happen inside of their neighborhoods and homes.”

Brett Lawson, the network’s executive director, said the school’s approach to discipline starts with changing the conversation around student behavior.

“If you switch the lens, and you say, this student who has done this behavior has had something done to them that makes them believe that this behavior is OK,” said Lawson. “That’s the trauma that we’re talking about.”

Lawson said the only time a student will be suspended, expelled, or receive an “out of school consequence,” is when they violate the state’s zero tolerance policy by bringing firearms to school, committing aggravated assault on a faculty member, or possessing drugs and controlled substances unlawfully.

Shelby County Schools has made its own efforts to change its approach to policing in schools, although not as far reaching as the superintendent had hoped.

In 2019, Superintendent Joris Ray proposed creating its own district police force, called a “peace force,” to replace sheriff’s deputies, but the school board turned down the plan.

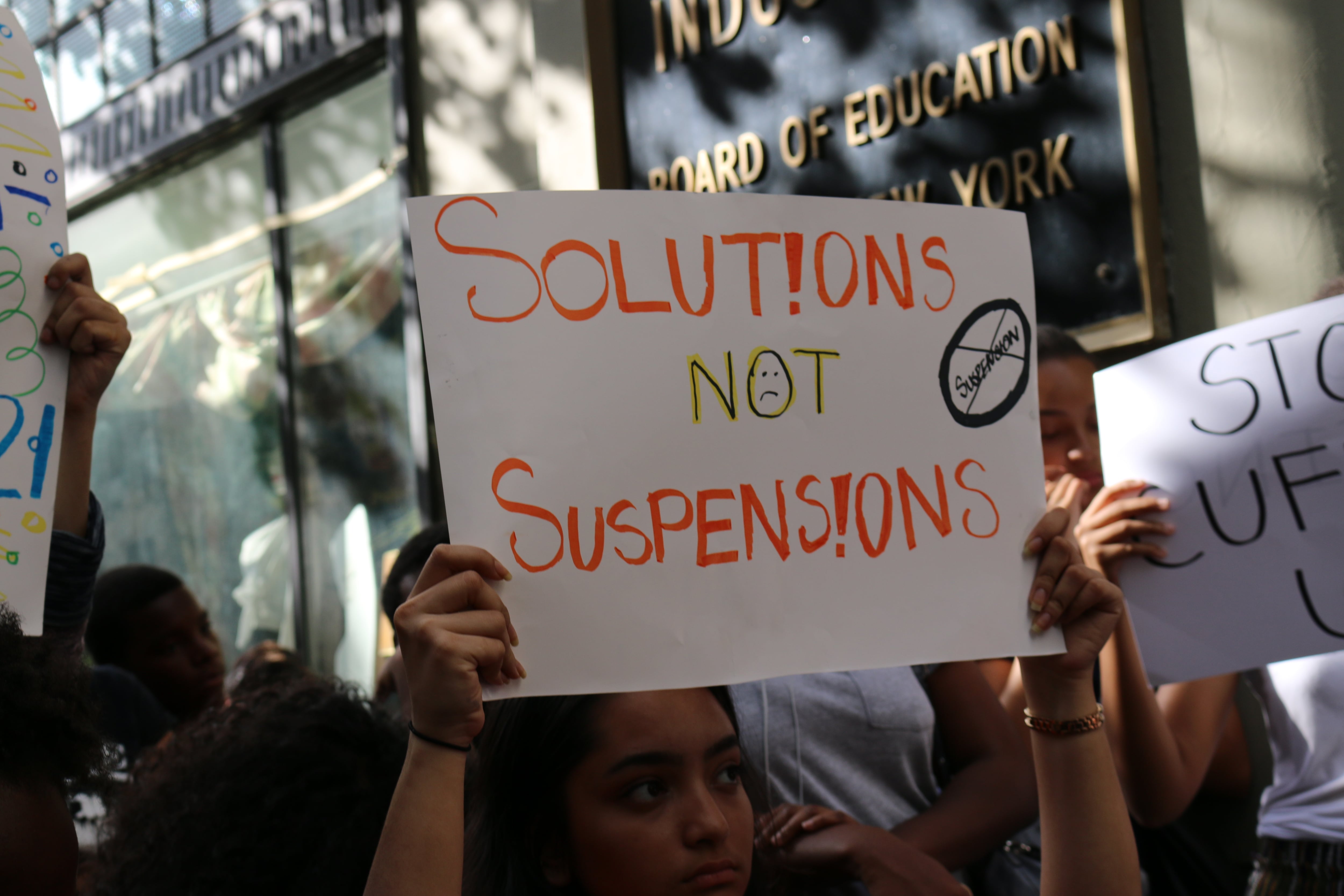

Nationwide, at least 28 school districts — including Minneapolis, Denver, and Seattle — have passed resolutions cutting ties with local police forces. Chicago has left the decision to remove officers up to individual schools and Philadelphia has renamed police “safety officers.”

According to a statement from the Memphis district, the district has 125 armed officers, including 45 Shelby County sheriff’s deputies. The statement said officers receive enhanced training in “addressing and recognizing problem areas that contribute to student violence” as well as training in nonviolence, crisis prevention, and gang reduction.

The district has implemented strategies to reduce negative encounters between police and students, including opening ReSET Rooms where students can calm down with a supportive adult after emotional or tense moments, according to the statement.

Since the expansion of the reset rooms in 2019, out of school suspension rates have decreased, dropping from 12.9% in 2018-19 to 9.1% in 2019-20, according to district records. Because the district switched to virtual learning for most of 2020-21, the percentages for last year dropped dramatically.

Education advocate Cardell Orrin, who is against armed sheriff deputies in schools, acknowledged that the district has made improvements. Orrin, executive director for Stand for Children, said that the district has reduced the number of students who enter the criminal justice system because of school incidents.

In 2018-19, there were 487 arrests and juvenile summons following incidents in Memphis high schools, and in 2019-20 there were 253, according to the Sheriff’s department. In 2020-21, a year when most Memphis students did virtual learning, there were only seven.

Orrin said that he hopes the district will continue the reforms that have led to the reductions in campus arrests. He added that the money used for sheriff deputies should be diverted to additional resources such as additional behavioral specialists to solve disputes, and counselors.

Additional staff members can address substance abuse, bullying, and fights. Although officers are often involved in these incidents, Orrin says they don’t have to be.

“It’s a whole community challenge, where we have to look at it differently as a whole, as an entire community,” Orrin said. “There is an assumption that we need some kind of law enforcement there. That’s a reflection of our entire community where we think that violence means more police officers. And that’s not the answer.”

Seventeen-year-old Zahra Chowdhury agrees. A member of Bridge Builders Change, she is part of a local coalition of students and nonprofit organizations that have urged Memphis schools to remove officers.

She said her friend still has scars on her wrist from being handcuffed by an officer five years ago during eighth grade.

“She had a verbal altercation with her teacher, and a police officer that was in the hallway saw it and cuffed her,” said Chowdhury.

“And it was like, well, if the police officer hadn’t intervened, they could have solved it within themselves, just by talking,” she added. “Another teacher could have come in, or if a counselor had been there in that situation, that would have been immensely helpful.”