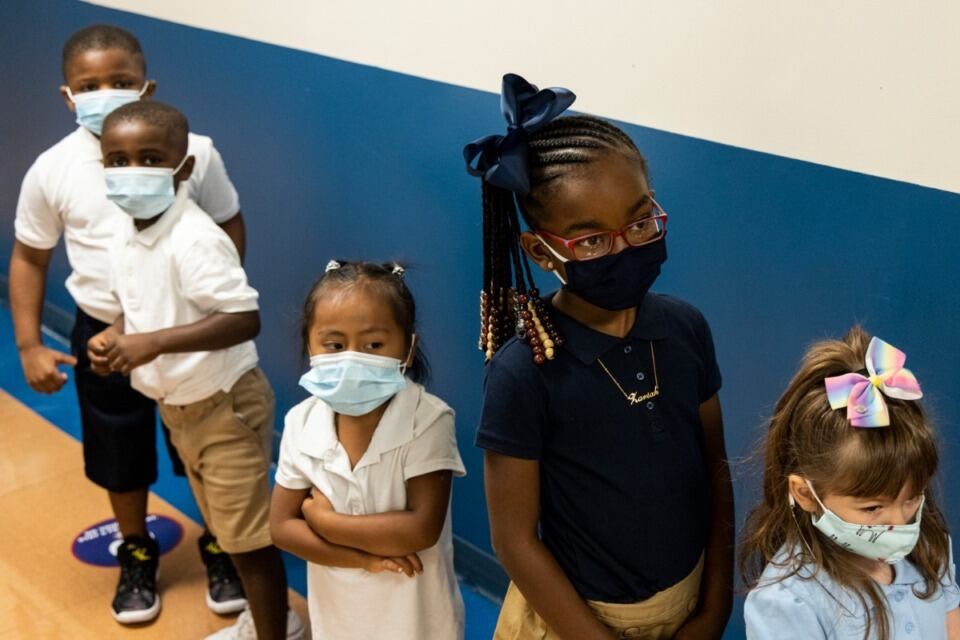

Gov. Bill Lee’s administration is getting pushback in Memphis on new Tennessee restrictions that make it harder for district leaders to close school buildings and shift students to remote instruction as pediatric COVID cases climb.

Meanwhile, school board members with Shelby County Schools held a moment of silence Tuesday to remember two students, two teachers, and one young alum who recently died. School officials did not release the cause of death for any of the five.

“We must stand together during this difficult time,” Superintendent Joris Ray said.

A day earlier, district officials encouraged families to direct their complaints to the governor’s office as a petition circulated demanding a virtual option that allows students to stay with their teachers. More than 13,000 people had signed the petition by Tuesday afternoon, and a small group of parents also protested outside the district’s headquarters on Monday.

“We hear your concerns and understand your frustrations regarding options for remote learning,” said a statement from the district. “Stand for safety with us by contacting Governor Lee and state legislators.”

The call to action reflects the ever-growing divide between the Republican governor and Tennessee’s largest school district over the best way to teach while protecting the health of children too young to be vaccinated. COVID’s delta variant has returned Tennessee’s case numbers to levels not seen since the pandemic’s wintertime peak.

Shelby County leaders said their hands are tied on remote learning options beyond enrolling in Memphis Virtual School. They cited new rules and criteria passed recently by the Tennessee State Board of Education for closing schools and remote learning.

Those rules allow individual students to switch temporarily to remote instruction if they’re sidelined by the virus, either because of illness or exposure. But districts can’t toggle back and forth with remote learning without an executive order from the governor, according to state officials. School systems that have to close entire schools because of COVID outbreaks must use days usually stockpiled for inclement weather, flu outbreaks, or staffing problems.

“We must comply with the law as we continue to push legislators to allow local control,” said the statement from Shelby County Schools.

After signing an executive order last week allowing parents to opt their students out of local mask mandates, the governor said he does not want students to return to remote instruction. He cited the results from testing last spring that show a dramatic decline in statewide achievement, especially in Memphis and Nashville, which stayed remote the longest.

“Currently, there’s no plan allowed for [students] to go back to virtual learning,” Lee said on Aug. 16. “So we’ll take that one step at a time, but our hope is that they won’t move in that direction.”

On Tuesday, his press secretary, Casey Black, said the governor’s office has received about 80 calls since then about remote learning. About half want the same kind of virtual flexibility they had last year, and the other half want school buildings to stay open, Black said.

Memphian Nikita Taylor, who has two children and a grandchild in Shelby County Schools, was among those weighing in. She contacted the governor’s office after learning about COVID cases at her children’s schools.

“My message to him would be that our children are not safe in the current conditions and under the compliances that you have in place,” said Taylor. “We need those to be adjusted so that our children can not only learn but so that they can also be safe while they are learning.”

Taylor wants her district to be granted flexibility to use a rotating schedule of in-person and remote classes allowing half of a school’s students to come to brick-and-mortar classrooms on Monday and Wednesday and the other half on Tuesdays and Thursdays. This would allow more space for social distancing in classrooms and help crews better disinfect the buildings, she said.

Taylor’s own children began the academic year in quarantine after testing positive for COVID before classes started on August 9.

“My children, they were just blessed to be healthy enough to fight it off, but there are some who may not be as lucky, and I’m really concerned about those children,” she said.

The governor has called the pandemic “an adult problem” that doesn’t require universal masking in schools.

His opt-out masking order drew a stern letter from U.S. Secretary of Education Miguel Cardona urging Lee not to block districts from following “science-based strategies for preventing the spread of COVID-19 that are aligned with the guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.” And another petition signed by nearly 6,000 Tennessee health care workers urges Lee to drop his executive order.

On Tuesday, the governor’s spokeswoman did not respond when asked via email about the surge in pediatric cases and whether schooling under the current restrictions is sustainable.

In a new COVID dashboard unveiled on Tuesday, Shelby County Schools reported 547 cases among students and staff in its first two weeks of school. And according to data from the Tennessee Department of Health, Shelby County has seen a 40% increase in COVID cases among children ages 5 to 18 — to about 2,400 cases — in the last week, as of 3 p.m. Tuesday.

On Monday, Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital in Memphis confirmed the death of its third patient this month — 16-year-old Azorean “Zo” Tatum, a student at Westwood High School — due to complications from the virus. By Tuesday, the hospital was treating 33 children with COVID, including nine in intensive care and two on ventilators.

At Tuesday’s school board meeting, district officials mentioned the death of a second student without providing details.

They also confirmed the deaths of two educators: Ashley Leatherwood, a second-grade teacher at Riverwood Elementary School in Cordova, and Catrina Brooks, a pre-kindergarten specialist at Grahamwood Elementary School in East Memphis.

The sudden losses have served as tragic markers in a young school year and added anxiety to school communities trying to navigate the stubborn pandemic.

“It’s just all so stressful,” said Taylor.