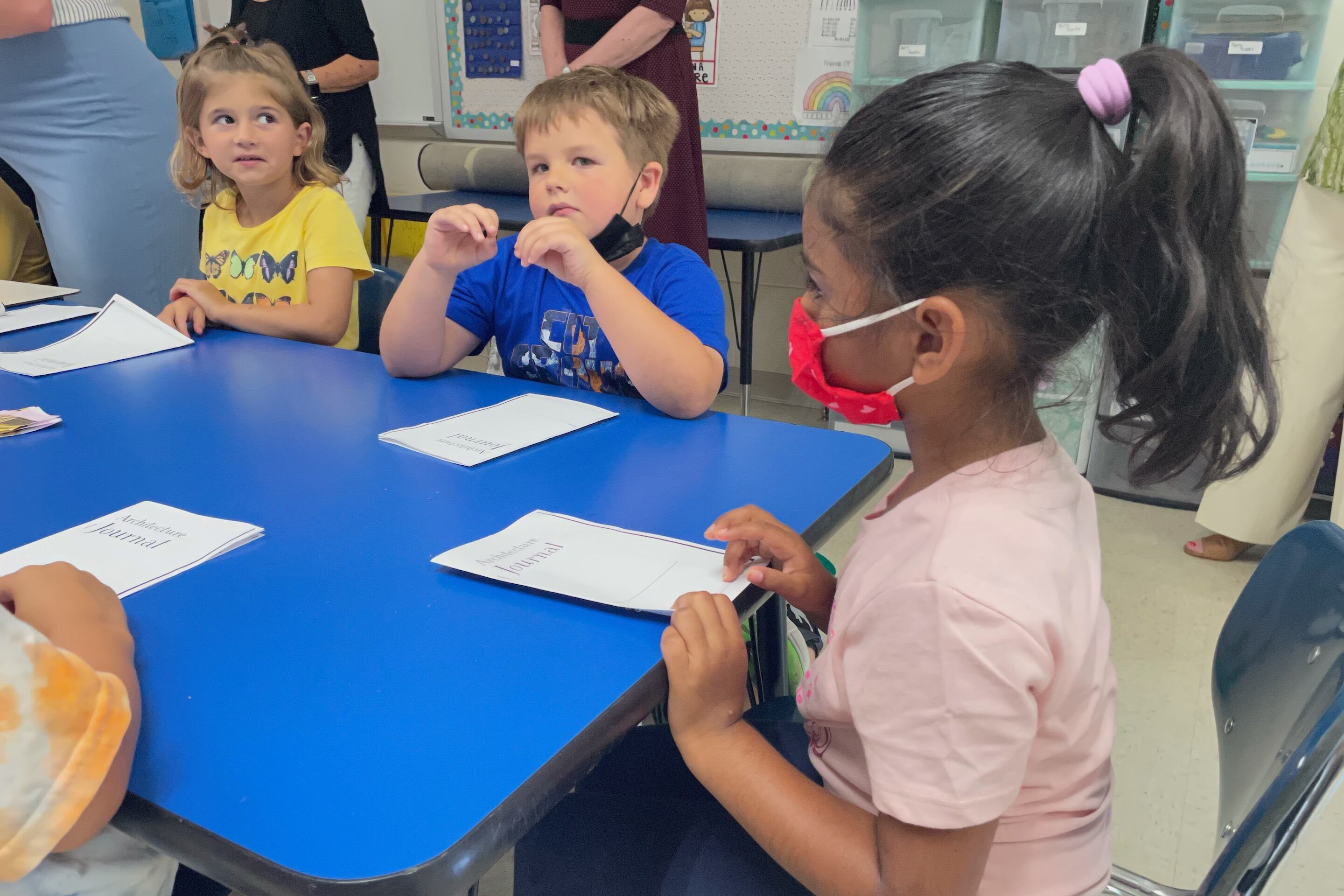

Tennessee mom Amanda Sharitt sent her three children back to school this week wearing masks, but she figures only one will actually use a face covering all day under their district’s optional masking policy.

“My 13-year-old daughter is very informed and plans to wear a mask, but my 11-year-old son has autism and finds them itchy and confining. As for my kindergartner, I’ll send her with a mask, but if it comes off, it comes off. I can’t do anything about that,” said Sharitt, who lives in Murfreesboro, south of Nashville.

After a year of universal masking requirements by most of Tennessee’s 147 school districts, less than a dozen have extended those mandates for the new academic year, even as the more contagious delta variant has reawakened the coronavirus pandemic.

The result is a state of mask confusion. For weeks, Tennessee students, parents, and teachers have been wading through a morass of conflicting statements from state and local officials, changing government directives, and shifting medical guidance.

“The information is bouncing all around,” fumed Sharitt, who wishes that Rutherford County Schools had required masks. “The CDC says one thing, our governor says something else, and then our local leaders say they’re just following what they’re being told. Nothing is consistent.”

Tennessee isn’t alone in its patchwork of policies. Illinois mandated face coverings last week, while Florida’s governor threatened to withhold funding from districts that require them. The governor of Arkansas is trying to reverse a mask ban he signed earlier this year. Cities like New York City and Denver plan to require masks, but many districts are still mulling what to do.

Last week, in a reversal from his previous message, Tennessee Gov. Bill Lee said parents should decide about masking, not local school systems. House Speaker Cameron Sexton agreed, threatening districts that require masks with voucher legislation to let public school parents move their children and taxpayer money to private schools.

Tennessee law says such decisions lie with local school boards and, in some cases, county health officers.

Parents like Michael Miller are fed up with the mixed messages, especially since the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American Academy of Pediatrics agree that all students and school staff should wear masks, regardless of whether they are vaccinated.

“It’s incomprehensible. Honestly, it feels like gross negligence,” said Miller, whose two sons attend schools in Williamson County, also near Nashville.

His school system, which started classes last Friday, has “highly encouraged” masks but isn’t requiring them so far this year, contrary to a pledge in March to follow CDC guidance when families had to choose between in-person or virtual classes for 2021-22. After a year of remote learning, the Millers chose to send their sons back into school buildings.

But at a recent open house at one of his children’s schools, Miller saw only about a fourth of the people, including teachers, wearing face coverings.

“I’m angry, upset, scared, concerned, because we just spent a year doing everything we could to keep our kids safe,” he said.

Another COVID wave arrives

The delta variant is spreading quickly, mostly among unvaccinated populations, with the number of Tennessee cases doubling in the last two weeks. Less than 40% of Tennesseans are fully vaccinated, compared with about 50% nationwide.

Most concerning is the surge happening among children, said Dr. Lisa Piercey, commissioner of the Tennessee Department of Health. During a call with reporters on Friday, she said pediatric COVID cases almost doubled to nearly 3,200 during the week ending on July 25.

“A lot of our pediatric cases are in the West Tennessee region right now, because of its proximity to Missouri and Arkansas. This is probably going to be across the state in the next few weeks,” Piercey said.

Even so, her department won’t recommend more restrictions at schools if the spread worsens among school-age kids.

“We’ve passed along the CDC guidance. We’ve passed along the AAPA guidance. We don’t have anything to add to that. Those two large national bodies have spoken, and we’re telling districts and parents, this is your choice,” Piercey said.

Tennessee wants to keep students learning in person as much as possible this year, especially after state test scores released last week showed an across-the-board drop in proficiency, particularly for students who learned mostly remotely.

Under new rules approved by the state Board of Education, Tennessee is allowing students to switch temporarily to remote instruction if they’re sidelined by the virus, either because of illness or exposure. But districts that have to close schools or entire systems because of COVID outbreaks will have to use days they’ve usually stockpiled for inclement weather, flu outbreaks, or staffing problems.

If districts and parents want to keep their students in brick-and-mortar classrooms, national guidance is “actually pretty clear,” said Dr. Stephen Patrick, director of the Vanderbilt Center for Child Health Policy.

“We need to have a layered approach to protection,” said Patrick, who is also a pediatrician. “The first layer is vaccines, the next is masks, and the last is proper distancing.”

Tennessee dialed back COVID protocols

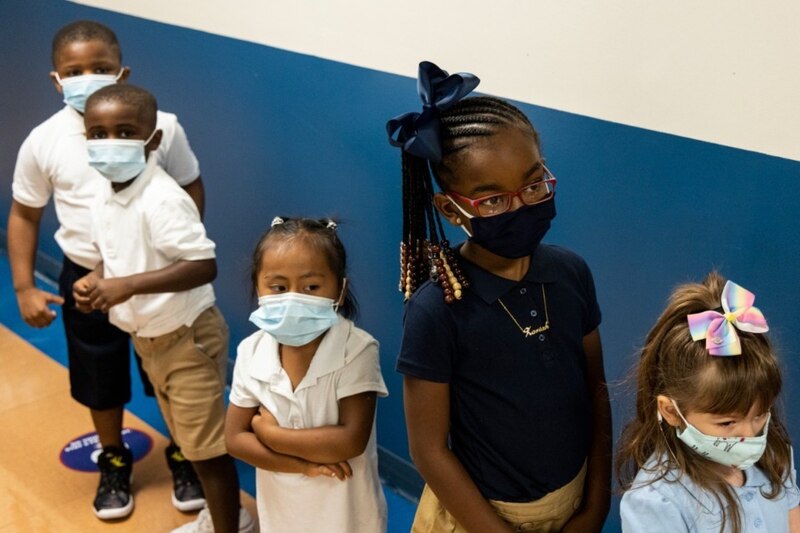

Tennessee isn’t set up to quickly follow all of those protocols. A new state law bans COVID vaccine mandates for most government-run entities, so public school teachers and school staff can’t be required to get inoculated. And children 11 and under aren’t eligible to get vaccinated yet.

As for mitigation, the delta variant spike has caught districts flat-footed after they rolled back COVID strategies like masking for summer school programs, with few problems.

On Monday, Arlington Community Schools, near Memphis, canceled the first day of classes at one elementary school due to staffing issues after several teachers tested positive for COVID following several days of staff training.

Last week, another district in Trousdale County, northeast of Nashville, quarantined nearly 200 students when a teacher and student tested positive at two of the district’s three schools. The rural school system reopened July 29 with an optional masking policy.

“We thought we were safe this fall after summer school went so well with optional masking, but we’ve been shocked by the potency of this variant and how fast it moves,” Trousdale Superintendent Clint Satterfield said Monday.

The masking policy will be reviewed again by the school board next week.

“We’re going to put the health and safety of our people first,” Satterfield promised, “and that’s probably going to mean more quarantines.”

Delta variant is a game changer

Dale Lynch, who leads the state superintendent organization, described the situation as “very fluid.” Some school boards are calling special meetings to review their protocols for face coverings, social distancing, and cohorting students into smaller groups.

When August began, Memphis-based Shelby County Schools was the only district that had announced a mandatory mask policy for the upcoming academic year. But with the recent COVID surge, at least 10 other districts have since reinstated their mandates. They include Metropolitan Nashville Public Schools, as well as six suburban districts in Shelby County that say they will comply with Friday’s local health order for all K-12 students to wear masks indoors.

The trend comes despite recent statements from the Republican governor and House speaker about possibly convening a special legislative session aimed at punishing districts with mask mandates, or banning such mandates altogether.

On Monday, Lee said he was disappointed in the Shelby County order, which he says overrides the decisions of parents and local school boards. While he would not say if he will call lawmakers back to Nashville, he said he is in talks with legislative leaders.

“Nothing’s off the table,” the governor said.

Shelby County health officials issued a statement Monday saying mask mandates are well within their authority under a state law that allows them to take action to “protect the general health and safety of the county.”

“That many children cannot be vaccinated and will be indoors during school sessions is one of the highest risks of transmission that Shelby County faces today,” the statement said.

Even among top state officials, there’s disagreement about whether the legislature should step into the heated discussion.

“While I am firmly against a statewide mask mandate, I trust locally elected school boards to do what is necessary to keep their students healthy and their doors open,” Lt. Gov. Randy McNally said in a recent statement.

Nashville mom Sonya Thomas has been listening closely and watching how officials have managed the virus across Tennessee. She says her faith in government is shaken as her district prepares to kick off a new school year Tuesday.

“I don’t trust when our leaders can’t sit down together and set politics aside and make good public health policy,” said Thomas, who leads a parents advocacy group called Nashville Propel.

“COVID has its own agenda,” Thomas continued, “and we need serious strategies for managing it. This whole conversation has turned into a pissing contest.”

Patrick, with Vanderbilt University, says he understands the frustration of parents like Thomas. He hopes they don’t give up and is encouraging them to act on guidance from the CDC.

“We are in an evolving pandemic that none of us have gone through before,” he said. “We need to understand that the guidance will change because the virus has changed. And we need to give each other some grace because the bottom line is that we’re all in this together.”