Tennessee’s textbook commission has wide new powers to determine which books students can and can’t access in public school libraries. But members say the panel doesn’t have enough resources to finish its most pressing new task: providing guidance to school leaders on how to comply with several recently enacted library laws.

The all-volunteer commission blew past a statutory Dec. 1 deadline to finalize its guidelines, and decided last week that it can’t do so without first getting legal advice.

“We have gotten zero guidance from any attorneys — zero. And we’re just out here as volunteers doing this,” said commission member John Combs, a school superintendent from Tipton County.

The new laws require schools to periodically screen their library materials for “age appropriateness,” based on local standards and community input. They also empowered the 13-member Tennessee Textbook and Instructional Materials Quality Commission to rule on appeals to local decisions about individual books — and to even ban challenged books statewide — a significant expansion of the commission’s original mandate.

With the commission’s final vote on guidance likely weeks or even months away, school administrators are on their own for now to figure out how to navigate changes in the law.

This month’s missed deadline, though, is a symptom of a larger concern that commission members are grappling with as they prepare for a potential onslaught of appeals of book challenges in a state that’s one of the nation’s leaders in banning literary, scholarly, and creative works.

When GOP lawmakers passed the library appeals law in the waning hours of the legislative session this spring, they provided no funding for the commission to hire staff to manage its new appeals work. The law’s fiscal impact was identified as “not significant,” according to an analysis by legislative staff.

But essentially, it was an unfunded mandate.

Established in 1983, the textbook commission has no offices, no full-time staff, and no independent lawyers with whom to confer. Most members have full-time jobs and lean on administrative support from the state education department to fulfill the body’s core responsibility of approving textbooks and instructional materials, and establishing contracts with publishers to guarantee availability to schools at the lowest price.

In its new appellate role over school libraries, the panel will have to dive into local disputes over age-appropriateness and community standards. That means setting up processes to make sure complainants are eligible to appeal, reviewing all documentation leading up to the local decision, and analyzing the materials in question, possibly with statewide consequences.

“It’s a lot of work to be added to people who already have a full load,” commission Chair Linda Cash told a legislative subcommittee in September.

Cash, who is school superintendent in Bradley County near Chattanooga, has asked Gov. Bill Lee’s administration for recurring funding to hire staff and set up offices similar to several other education agencies. For instance, the 2-year-old Public Charter School Commission, which Lee championed, has a 14-member staff to help its nine appointed members manage charter school appeals. The State Board of Education has 15 employees who help its 11 appointees set policies ranging from academic standards to teacher preparation and licensing requirements.

In a Nov. 22 letter obtained by Chalkbeat, Cash told Tennessee Finance Commissioner Jim Bryson “it is imperative” that the commission hire an executive director, an attorney, and administrative support to help it carry out both its old and new responsibilities. And during last week’s commission meeting, she also cited the need for a policy adviser and additional support from the state education department.

“Our goal … is to follow the legislative intent and to provide guidance on this law on the age-appropriate materials in school libraries,” she told fellow commissioners. “Limited staffing often makes our task more difficult.”

Rep. John Ragan, who co-chairs the legislative committee overseeing government operations, has endorsed Cash’s request. He called the panel’s newest charge from the legislature “yeoman’s work.”

“If they need additional support, let’s make sure we try to get it for them,” the Oak Ridge Republican told representatives of the state education department in September.

But state Rep. John Ray Clemmons, a Nashville Democrat who spoke against the school library bill on the House floor, questions the need to add another bureaucratic layer and notes that the legislation came from the political party that claims it’s for less government and more local control.

“The core function of the law is to pull books off of bookshelves, and now we’re faced with implementing this bad and dangerous education policy,” Clemmons told Chalkbeat. “Tennessee taxpayers are going to be on the hook for the whole thing.”

Number of expected appeals remains uncertain

As commissioners seek to staff up, the big unknown is the workload they’ll face under Tennessee’s new school library laws, which were enacted at the urging of Lee and House Speaker Cameron Sexton following several high-profile challenges over books and curriculum in 2021.

Katie Capshaw, president of the Tennessee Association of School Librarians, says it’s “very rare” for school librarians to receive complaints about items in their collections in the first place.

And Cash has been optimistic that local attention and diligence in addressing complaints will make appeals unnecessary.

But Commissioner Laurie Cardoza-Moore, whom Sexton appointed from Williamson County to represent parents and who has allies in the conservative activist group Moms for Liberty, has said the panel should prepare for a wave of appeals once it formally establishes its appellate process next year.

“I just received a packet that I shared with all of you this morning,” she told fellow commissioners last month, “and there are numerous items that are being challenged.”

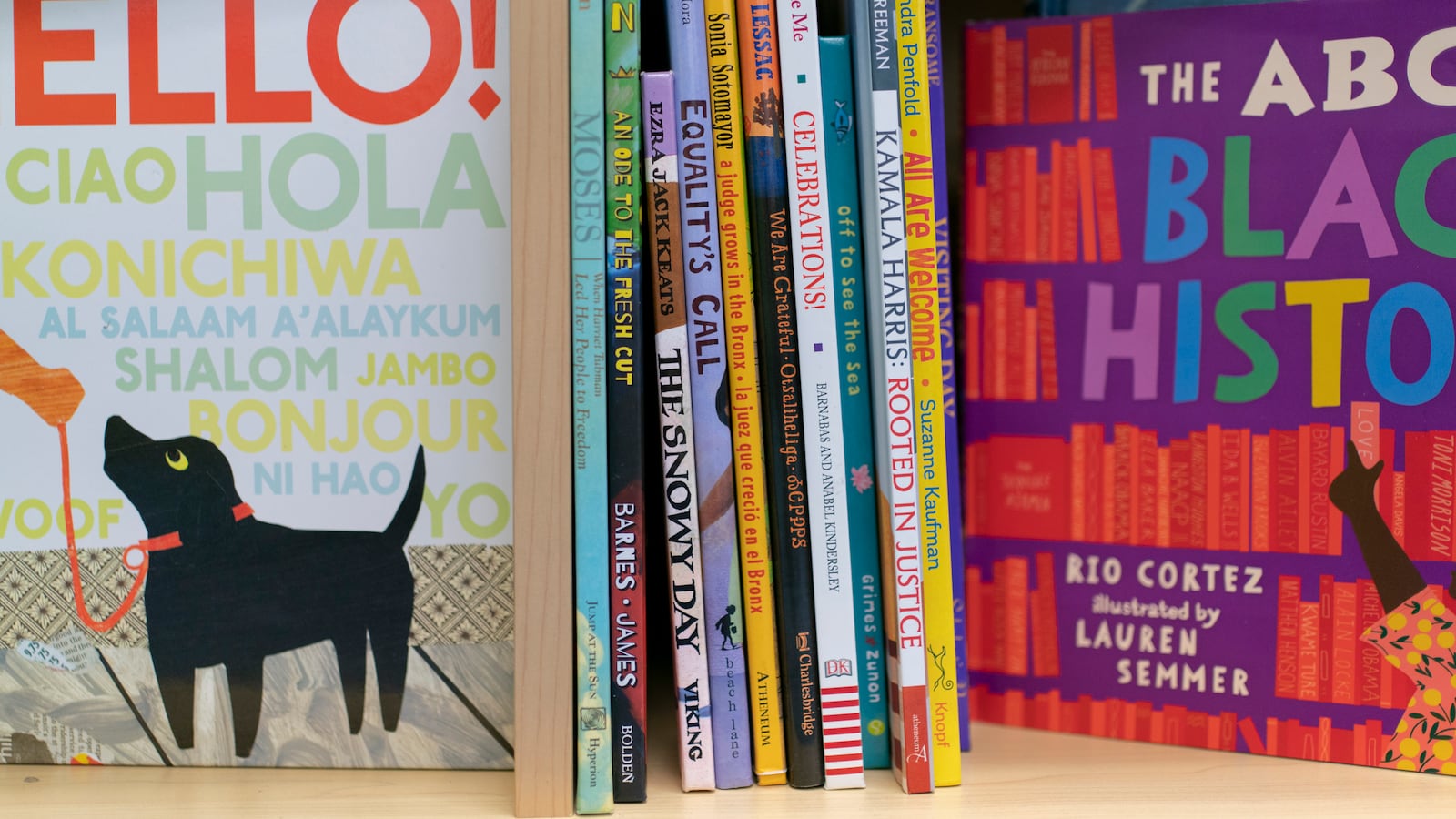

According to PEN America, a group that advocates for free expression in literature, Tennessee trails only Texas, Florida, and Pennsylvania in logging the most restrictions or attempted restrictions on books. Most of the objections have to do with sexuality, LGBTQ themes, and issues related to race and racism.

In the last month, school leaders in at least two Tennessee districts have addressed book complaints with different outcomes.

Wilson County Schools, east of Nashville, pulled two books that its board deemed sexually graphic — “Tricks” and “Jack of Hearts” — from high school libraries.

Sumner County Schools, north of Nashville, voted to keep “A Place Inside of Me” on its shelves. The book includes a poem and illustrations showing a Black child dealing with his emotions after a police shooting.

Nationwide, the number of attempts to ban or restrict library resources in schools, universities and public libraries in 2022 is on track to exceed record counts from 2021, according to preliminary data released in September by the American Library Association.

Commissioners may not have to read an entire book

Tennessee’s textbook commission has been drafting broad guidance for school districts on how to comply with the laws. Much of its draft is based on model guidance developed by the Tennessee School Boards Association and already used by many school boards and charter school governing bodies across the state.

During last week’s two-hour virtual meeting, commissioners nailed down a timetable that would require complainants to file their request for appeal within five school days of a local decision. The originating district or charter school would then have up to 20 school days to submit documentation of deliberations and decisions. And the appeal would be heard at the next regularly scheduled meeting of the commission, which meets twice a year.

Among the panel’s considerations would be whether the material is suitable and consistent with the school’s educational mission; appropriate for the age and maturity levels of the students who may access it; containing literary, historical, and/or artistic value and merit; and offering a variety of viewpoints.

A student, parent, guardian, or school employee would be able to file only two appeals in a single year. And appeals couldn’t be filed on a book that the commission has already ruled on until after three years, which would be timed to the appointment of new commission members.

But commissioners wouldn’t necessarily have to read an appealed book in its entirety before voting — unless they want to.

Commissioner Lee Houston, a school librarian in Cumberland County, sought to include that requirement because “context is important,” she said. But her motion failed for lack of a second after Commissioner Billy Bryan said a simple review should be sufficient, without reading the entire book.

“We don’t know how many appeals we’re going to get and how many books we’re going to be required to read,” Bryan said. “And there’s a limited amount of time on my already busy schedule for reading who-knows-how-many library books.”

Tennessee school leaders await final guidance

Since the commission has no staff attorney of its own, members voted to seek legal counsel from the state attorney general on its draft guidance, but to go to lawyers for the legislature or education department if necessary.

In the meantime, school leaders are relying on their own processes for reviewing challenged books and materials.

“I believe we’re in compliance with these new laws, but it would be affirming if the commission could reinforce what we’re already doing,” said Danny Weeks, director of Dickson County Schools, west of Nashville, where the school board has voted on two book challenges in 10 years.

“State guidance,” he added, “would be nice to have.”

Marta W. Aldrich is a senior correspondent and covers the statehouse for Chalkbeat Tennessee. Contact her at maldrich@chalkbeat.org.