On one of the toughest days of his teaching career, there was tenacity, transparency, and tears.

“Today has been heavy,” admitted Adrian Hampton.

Hampton, 41, has spent half of his life as a math teacher at Booker T. Washington Middle and High School, known as BTW. During his time at the Memphis school, he’s lost multiple students to gun violence, including 15-year-old Damien Smith, Jr., who was shot the day before Hampton’s interview with Chalkbeat.

The police charged 38-year-old Marcus Orr with the fatal shooting, and videographer Twan Freeman filmed Smith’s vigil a few days later. Since the beginning of the school year, at least 23 children have died by homicide in Memphis, according to police data.

Scheduled days before the shooting, the interview was initially set as a time to chat about Hampton’s legendary teaching career, which was shaped by two former teachers, Snowden School science teacher Clarence Estes and Central High School math teacher Rick Yates. In 2021, Hampton was a finalist for the district’s teacher of the year award, a nod to both his talent and his longstanding commitment to working in a school where children need extraordinary support. About 90 percent of BTW students are economically disadvantaged, according to the state.

Hampton has served the BTW community for 20 years — or 22 years if you count his two years there as a student teacher. He has now taught math to two generations of families at the school. Just over a decade ago, he and the senior Class of 2011 got a backstage meeting with then-President Barack Obama who served as the school’s commencement speaker.

“The first Black president, and he’s at BTW,” said Hampton.

“The kids cried. The toughest guys were in the back crying when he walked behind the curtain. It was amazing,” he added.

But mixed into a career of incredible highlights are the devastating lows of losing a student, which Hampton discussed, as he reflected on how he teaches while facing sorrowful young faces and an eerily empty desk.

How are you doing today?

Today’s been different. I’ve taught here for so long that I’ve lost a lot of kids, so you don’t ever want that to become normal. Yeah, today’s been heavy.

You could have taken the day off, and you didn’t. You came back to school today. Why?

We got a job to do. We tell kids not to make excuses. And not saying that this would be an excuse, because you got to take care of you first, because if you’re not taking care of you first, then, of course, you can’t take care of everybody else, but you lead by example. You show the kids that it’s OK to corporately come together and grieve.

How do you approach such a heavy time with your students?

It was solemn in the class. I was able to still get in some instruction but not hover over them. We had grief counselors in the building today, so I just kind of let them be to themselves. If somebody had their head down, I didn’t bother them today.

We don’t hear enough Black men discussing and expressing grief, and I just want to acknowledge that and applaud you for that. How do you take care of yourself at this moment?

I think you just helped me in making me talk about it just then. I really hadn’t talked about it for real until you just asked me that question, so that just allowed me to get out some emotions that I didn’t even know that I needed to get out.

So many teachers move around. Why have you stayed at Booker T. Washington?

The relationships — not only with the kids, but some of the other teachers have served just as long as me. The Algebra I teacher has been here 21 years. The guidance counselor, she’s been here 21 years. If you can deal with the neighborhood and working in this environment, our teachers really don’t leave. So you build relationships with your coworkers, and you build relationships with families.

Some of my former students are my parents now. So, I wouldn’t leave at this point. It’s ingrained, and kids know kind of what to expect because I’ve taught so many of their family members that, honestly, it makes it easier every year. I don’t have to adjust. The kids know my reputation.

You have a reputation for being relatable. How do you create such a strong connection with your students?

I let them know that I care from day one. If they play sports, I’m going to their sporting events. If they’re in the choir or in the band, I support them in things that they do. I let them know that I care about them as a person and that they’re not just a student in my class. I bring my kids up here, and they know my kids. My wife used to work here.

What has it been like connecting with and teaching students during a pandemic?

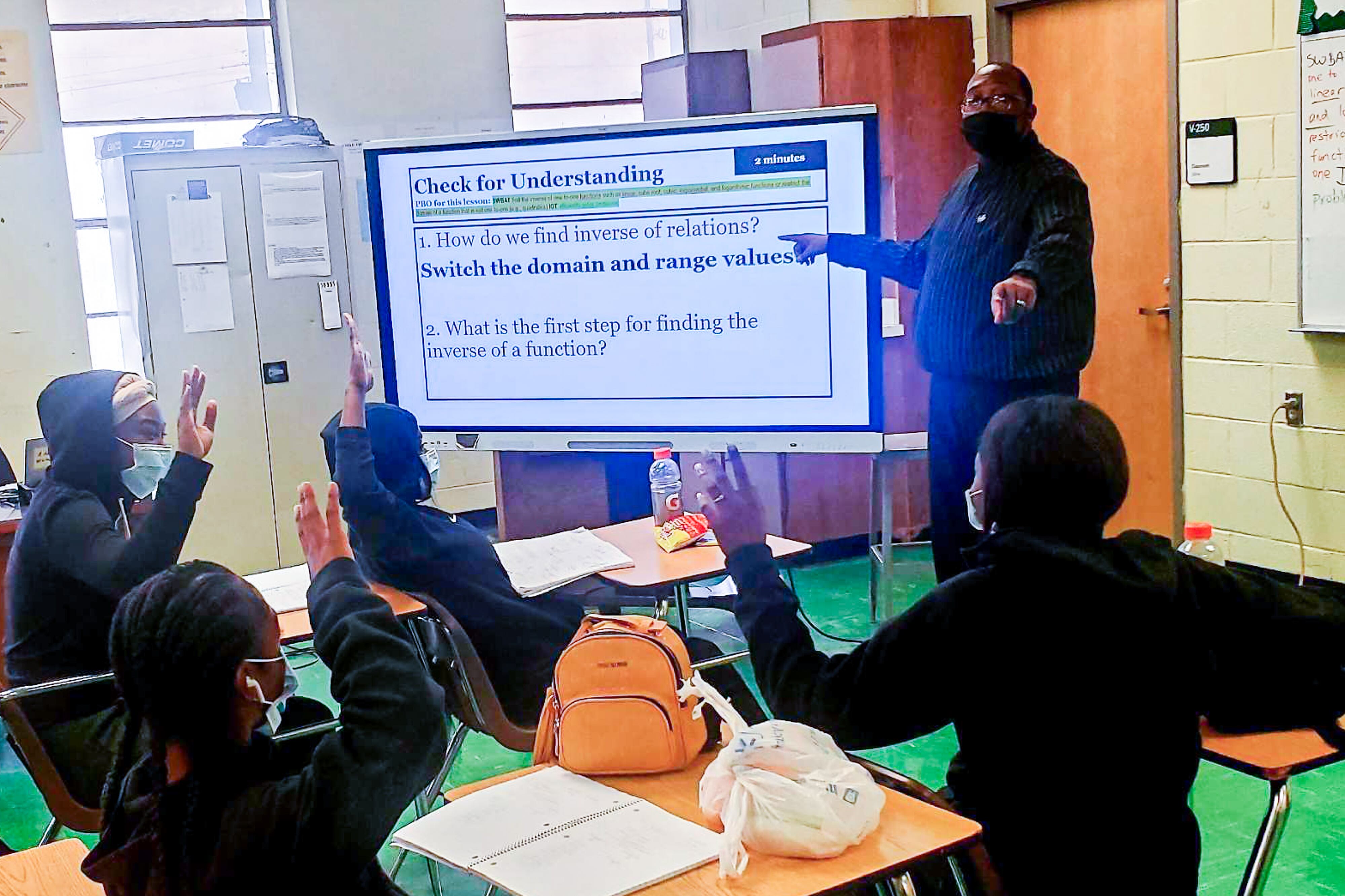

The biggest thing is that the attention span isn’t as high as I saw with those kids two years ago. You have to constantly be doing something to keep their attention and making sure that everything isn’t the same for that full 75 minutes that they’re in class with you. You have to have things in place that are going to allow kids to move around a little bit as much as we can. We don’t want anybody getting COVID or anything, but keeping them moving a little bit. Giving them brain breaks at certain points. Those are things that were talked about before the pandemic, but they’re absolutely necessary now.

As far as socialization, some of our kids never really stopped being around each other to a certain extent, but they weren’t around grown people. Discipline has been something that we’ve had to refocus on. That’s something that we’ve had to hone in on to make sure that they understand how they’re supposed to act when they’re in the building. We teach code-switching, making sure that you know how to act when you’re around your friends, but also knowing how to act when you’re around grown people.

Do you guys actually call it code-switching?

Yeah, we call it code-switching for sure.

As we emerge from the pandemic, what gives you hope at this moment?

What gives me hope is that kids see when you’re genuine. My dad’s a preacher, and he says all the time, all you can do is plant and water. You may not see the increase, but you know that you planted and watered, and that’s what teachers do. We give them instruction. We give them the tools to make them, hopefully, be the best they can be, and you may not see the fruits of your labor during that school year, but you sleep well at night knowing that you did your best.

And do you know that you did your best with Damien?

I regret not saying something to him yesterday. That goes back to what I said earlier, you can’t waste time. You always think, “OK, let me go ahead and get through this lesson, and I’ll talk to him at some other point when I get him by himself.” But, I know he knows — wow, I know he knew that we cared about him.

Bureau Chief Cathryn Stout, Ph.D. oversees Chalkbeat Tennessee’s coverage. Contact Cathryn at cstout@chalkbeat.org