Over the quarter of a century that Memphis-Shelby County Schools Superintendent Joris Ray has worked in education, he’s faced countless challenges. But none of them — not even a pandemic that forced instruction online — compares to the obstacles this school year.

“I told my team at the start of this year: This will be the hardest year we will ever have,” said Ray. “And it was.”

Within the first 30 days of school, which marked many students’ first face-to-face instruction in 18 months, MSCS faced a COVID surge fueled by the delta variant. The next month, a shooting in a stairwell at Cummings K-8 Optional School in South Memphis left a 13-year-old boy injured, another student in custody, and the entire community reeling. And then, in January, students’ return from winter break brought on yet another COVID spike due to the omicron variant.

Similar struggles at school districts across the nation have sparked concerns about a superintendent exodus: A recent RAND survey of 350 district leaders revealed that more than a quarter planned to leave their posts imminently. More alarming, according to the report: Leaders of urban districts like Memphis, which tend to serve mostly students of color who were disproportionately impacted by the pandemic, are leaving in higher numbers than their suburban and rural colleagues.

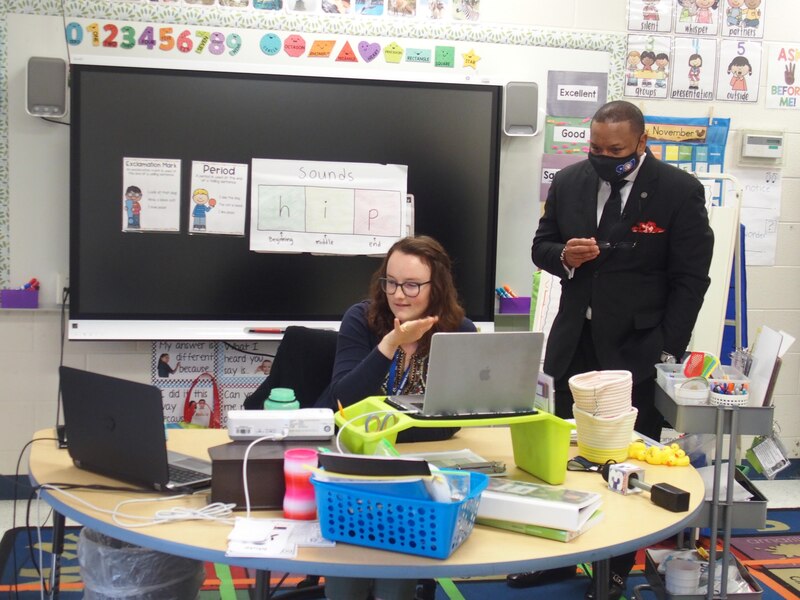

Ray said what makes him determined to press forward are his daily visits to classrooms that remind him of why he got into education in the first place: children.

In a rare one-on-one interview with Chalkbeat on a recent Friday at Rozelle Elementary School, Ray shed light on how his personal struggles years ago as a Memphis student shaped his career and why he’s remained positive despite the hurdles he’s faced since the pandemic began.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: A lot of us thought it would be the return to normal this year, and it was not. What challenges or successes did you experience this year?

A: This was the first time all students were returning back to school after being out for a year for virtual learning, and you still had to mitigate for all the risks of the pandemic.

Students had to wear masks, they still had to social distance — they had to do all of that. You had the rise of delta and the omicron variants. You’ve got the national disciplinary issues with children being out of school for a year, and they’re coming back trying to acclimate themselves back into the school district. You have parents, teachers, and students still fearful.

“We highly politicize basic educational things.”

The basic needs are food, water, shelter, and safety. If your basic needs aren’t met, it is very difficult to get to the top of the pyramid [in Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs], and that’s self actualization, right? And our students, coming back to an environment where they were very fearful — folks had on masks, teachers had to adjust the teaching styles — it was just very, very difficult.

And then the political polarization around everything was massive. You know, we’re having these debates on whether you should wear masks or not. … We highly politicize basic educational things — from books to critical race theory.

Q: There have been reports and news coverage this year about low test scores. How have those reports and other things affected morale in the district?

A: Many teachers, principals, even parents, were upset about it ... . Our principals, our teachers, our students are more than a number, and it is my job to keep the energy high. It’s my job to continue to keep everyone focused on the task at hand. And it’s my job to just continue to lead through the moment and inspire others. And that’s what I’m going to do as a leader — I’m going to inspire us to take it to the next level.

Back in the late 1970s, early ’80s, and even the ’90s, Memphis was the city to go to in Tennessee. But look at it now, you know? Why is that? It’s because Nashville has really galvanized their support, and worked together with one another. And as I traveled the streets and just from talking to the citizens there, they had nothing bad to say about the city. They had nothing negative to say about the school district. It was about the beauty of Nashville and the growth of Nashville, and how they wanted to continue to grow and do more. And I think as a city, we can learn a lesson from that.

Q: Another big challenge schools have faced is teacher shortages. How have you tried to address that issue?

We work to remove barriers out of teachers’ way and allow them to do the job that they love to do. But also, I don’t allow certain organizations to create noise for teachers or to speak as if they’re speaking for teachers. I speak directly to teachers every day. Every single day. …I get phone calls, I get text messages, I get emails from teachers every single day. … And they’re usually uplifting messages or suggestions.

Here’s a prime example of how you uplift the spirit of teachers: It’s listening. … An instructional coach called me and she was talking to me about how to better prepare our teachers and she had a recommendation. …

“I wish we could prepare teachers better before they transition to the classroom so that, when they get to us, some of the basic things that teachers should know, they will know,” she said.

That’s how we started what’s called the New Teacher Academy in 2022: by listening to teachers and fellow administrators. …. That’s how you boost morale. That’s how you keep teachers excited.

But we also have to pay. We’re recruiting nationally, working with our colleges and universities, but also, we want to retain the teachers that we have. …We do everything we can, but our teachers are tired. They’re tired.

Q: You recently kicked off the “Literacy is Life: Believe For It” tour. What prompted the event, and what’s the purpose?

A: I wanted a heavy focus on literacy. That’s my primary goal, that’s our number one focus: teaching children how to read at or above grade level by the time they make it to third grade. I’m committed to that. I know my team is committed to that. So that is what the Literacy is Life tour is all about. It’s about giving parents strategies on how to help their children at home.

“No matter how much we want to get things back to normal, things still aren’t normal.”

But also, it’s about telling the great things about this school district. It’s my job as the leader of this district to inspire others to greatness and to add fuel to the fire, so to speak. Our students are getting ready to take, yet again, another state standardized test in the midst of a pandemic. No matter how much we want to get things back to normal, things still aren’t normal. …

I’m just trying to create energy and excitement [in the city]. We have challenges, yes. We’re not shying away from our challenges, and we’re not shying away from our data. But we can chew gum and walk at the same time. Folks act as if, “Oh, they’re just focusing on changing the school district name.” No, it’s all in the big plan, a big strategy to uplift our children, uplift our district, and provide a world-class education. And then you’re gonna see the results are guaranteed.

Q: You said earlier this year that you planned to ask the Tennessee Department of Education to, for the third year in a row, not count standardized test scores for student letter grades or teacher performance evaluations. As we head into state assessment season, have you heard any more about that from the state?

A: Penny Schwinn, the commissioner of education, and I met, I want to say in February, and we did discuss it. And I know she’s working on some type of plan. And so I wanted to give her an opportunity.

And let me say this, the commissioner and I have a great working relationship. I respect her immensely. What she’s trying to do to provide equity across the state, she gets it, and I respect her for it.

Q: How did your own background shape your perspective on education?

A: I’m the youngest of seven children. My parents didn’t have a formal education. If you look at what research says about me, with both of my parents being high school dropouts, research says there’s a 50% chance I’m supposed to be a high school dropout. But through a quality education, and caring teachers, look at where I am today. …

“I want something more for our students, each and every day. They deserve it.”

My mom had a brain aneurysm when I was 12 and almost died. My pre-algebra teacher, Ms. Wright, looked at me and knew something wasn’t right with me. Every day she checked on me. Not only academically, but she checked on my well-being socially. She checked on my mental health. She hugged me. Teachers matter. That’s what shaped me in every decision I make — those moments, things that I learned. She wanted something more for me, and she understood what I was going through at home.

And oftentimes people don’t write about that, or they don’t think about the adversities our students bring to school with them. And I just think about that time period of my life, the adverse childhood experience that I brought to school, and it took that teacher — many of my teachers — wrapping their arms around me. ... So teaching goes far beyond what we can ever imagine. That’s what I bring to the table because I want something more for our students, each and every day. They deserve it.

Samantha West is a reporter for Chalkbeat Tennessee, where she covers K-12 education in Memphis. Connect with Samantha at swest@chalkbeat.org.