Hours after his school day ended Friday, 16-year-old Caleb Carpenter made his way to the Interstate 55 bridge connecting Memphis and Arkansas to join protesters who had gathered after the release of footage showing the brutal beating of Tyre Nichols by police.

“I’m tired of seeing all the Black-on-Black crime, but I feel unsafe with the police now, after that video I saw,” said Caleb, who attends Memphis Business Academy, a charter school. “I hated that it was Black police officers doing this to him, and I couldn’t do anything but question why.”

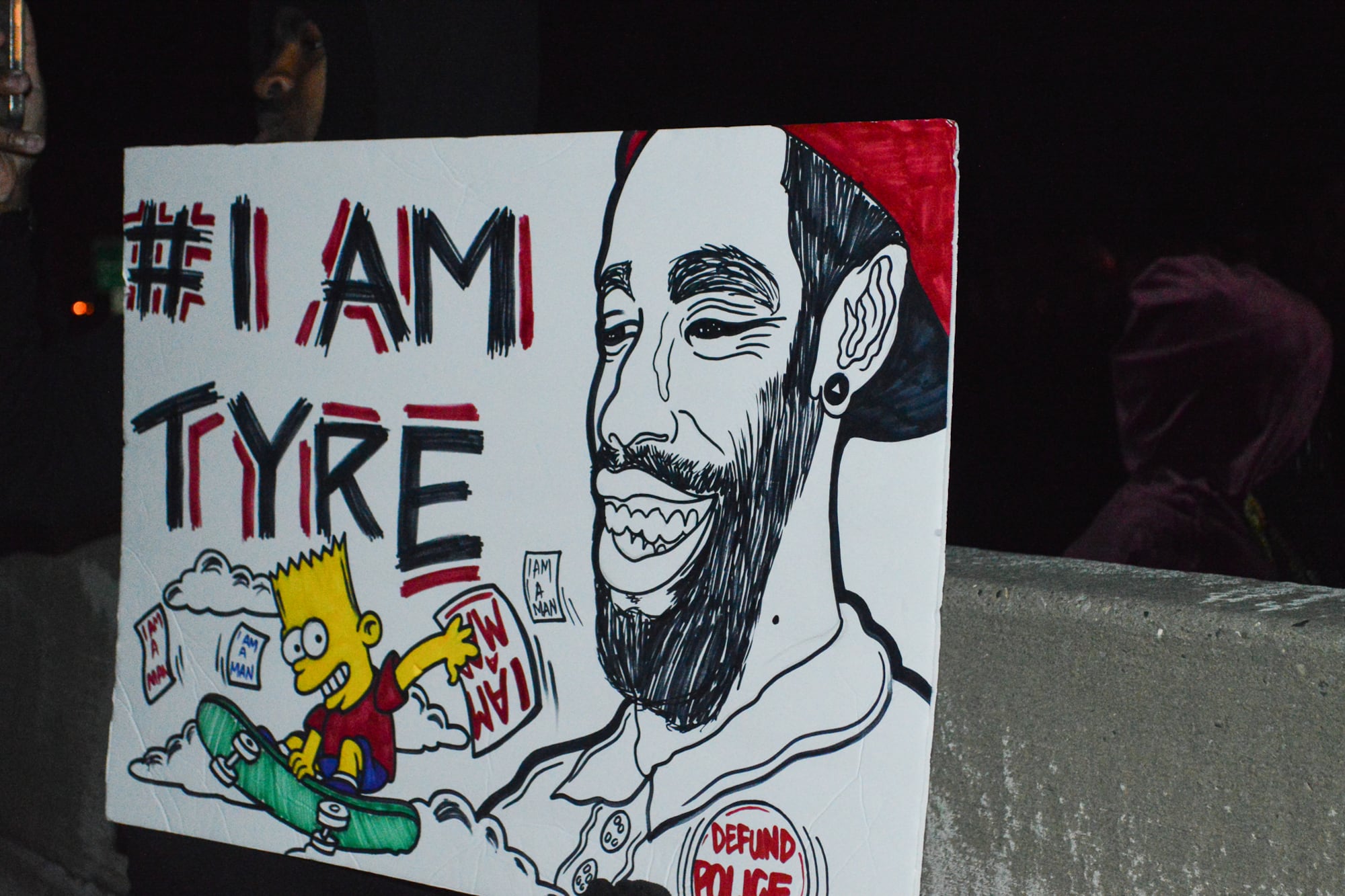

The area near the bridge was the scene of similar demonstrations in 2020 following George Floyd’s murder. Now the demand for justice was for one of the city’s own, a 29-year-old skateboarder, nature photographer, father of a 4-year-old son and FedEx employee who was simply trying to go home on Jan. 7 when he was stopped by Memphis police officers, tossed to the ground, cursed at, kicked, and pummeled as he cried for his mother.

Some protesters held skateboards in solidarity. Others held signs reading, “I Am Tyre Nichols,” “Justice for Tyre Nichols: Jail Killer Cops,” and “The People Demand: End Police Terror.”

Chants went up: “Say his name! Tyre Nichols,” and “No Justice, No Peace.”

Dylan Goodwin, a student at Collierville High School, said on Sunday that Nichols’ death has reinforced longstanding fears about the police.

“When it comes to Black people, the first thing I heard about the police was to keep your hands on the wheel, to be real cautious around them, and to say, ‘Yes sir, no sir,’” said the 16-year-old, who did not attend the protests.

“So now, it’s [a Black man killed by police] happened again, and it’s sad…I got used to talking around police, and being wary around police, and not particularly trusting them in general.

“It’s sad, because I’m 16, and I just want to live my life and enjoy it, and not have to worry about the people who are supposed to be protecting me.”

Memphis-Shelby County Schools let students out early on Friday and postponed after-school activities and Saturday athletics because of worries about potential unrest.

At least one study suggests that police violence may also cause Black and brown students to struggle academically. A 2021 study published in The Quarterly Journal of Economics focused on high school students in Los Angeles who lived in neighborhoods where incidents of police-involved killings were common.

It found that “exposure to police violence leads to significant decreases in the educational achievement and attainment of Black and Hispanic students…

“These effects are largest following police killings of unarmed minorities and differ meaningfully from those of criminal homicides, which produce smaller spillovers that do not vary with the race of the deceased.”

That may also contribute to education inequality, the study found: It estimated that officer-involved killings caused nearly 2,000 students of color from underrepresented communities to drop out of Los Angeles schools during the period studied.

As Caleb Carpenter and other young people clamor for police reforms, they know what’s at stake: To live in a place without the specter of being killed or brutalized by police.

That’s why Caleb said he joined the activists at the I-55 bridge.

“I’ll keep protesting,” he said.

Bureau Chief Tonyaa Weathersbee oversees Chalkbeat Tennessee’s education coverage. Contact her at tweathersbee@chalkbeat.org.