A state committee studying whether Tennessee should reject federal education dollars heard a unified plea from public school leaders not to do that — and to instead invest the state’s excess revenues in K-12 students, teachers, and schools.

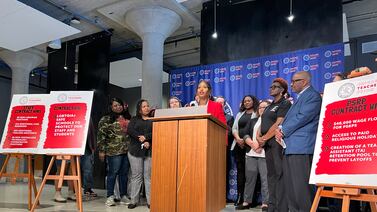

“The needs are so great,” said Toni Williams, interim superintendent of Memphis-Shelby County Schools, Tennessee’s largest district, during remarks Tuesday before the panel.

She described dozens of school buildings that are over a century old, outdated HVAC systems, and the need to mitigate everything from mold to rats. Last year, a library ceiling collapsed at Cummings K-12 Optional School, injuring the school librarian and two other staff members.

“This year has been incredibly difficult,” Williams said of her district’s work to address its ailing infrastructure while also providing teachers and staff with competitive pay and preparing for an end to federal COVID relief funding.

The plea from Williams and three other district leaders ran counter to the panel’s charge to develop a strategy on “how to reject certain federal funding or how to eliminate unwanted restrictions.”

Tennessee receives about $1.8 billion in federal funds for education. The U.S. government generally covers about a tenth of a state’s spending for public schools. No state has ever said no to federal funding for its students.

But leaders of Tennessee’s GOP-controlled legislature say they’re frustrated by the federal oversight that’s attached to receiving the money. Many of them believe the state can afford to forgo federal funding and fill the gap with state money.

The committee, appointed by the speakers of the House and Senate, kicked off hearings into the matter this week and is to report its findings and recommendations to the General Assembly by Jan. 9.

Federal funding cutoff could force tax increases later

On Monday, officials with the state comptroller’s office reported that districts in low-income and rural areas depend the most on federal funding. That money is directed to schools that serve disadvantaged students and programs that target certain needs ranging from rural education and English language learners to technology and charter schools.

On Tuesday, researchers with the Sycamore Institute, a nonpartisan think tank, said “much is unknown” if the state opts to pull out of the federal funding stream.

“There’s no precedent upon which to make projections,” said Mandy Spears, the institute’s deputy director.

Even with lower-than-projected revenues and experts predicting stagnant revenues ahead, Spears told the panel that Tennessee likely has room in its budget to replace federal dollars with state money. However, possible ramifications could include budget cuts or tax increases during a future shortfall or recession; protracted court battles over federal requirements that may still exist for schools even if funding is refused; and Tennesseans having to pay federal income taxes for education support that would go to other states.

Spears said federal requirements tied to federal funding provide an extra layer of accountability that’s important to many students and their families because of Tennessee’s history of racial discrimination, school segregation, and exclusion of students with disabilities from public schools.

“Students and families in these protected classes may worry that such practices could return in the absence of federal oversight,” Spears said.

Later Tuesday, the panel asked school district leaders numerous questions about staffing costs related to federal compliance and whether replacing federal funds with state money would give them more flexibility. They also questioned the superintendents about whether their districts measure how much federally funded food is wasted in school cafeterias.

They don’t.

“We just report the number of meals served every day,” said Williams of Memphis-Shelby County Schools, where food and nutrition is the second largest federally funded program at a cost of $89 million from the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Williams said 60% of the district’s 100,000-plus students are considered economically disadvantaged.

“Some of these students wouldn’t have an opportunity (to eat), if not for our food and nutrition program,” she said.

District leaders say extra funding is needed

Asked for a list of burdensome requirements associated with federal education funding, none of the school leaders spoke up. But they spoke at length about the need for more funding for public schools and their students.

Marlon King noted that Madison-Jackson County Schools, where he is superintendent, is among several districts in West Tennessee making investments to develop the future workforce for Ford Motor Co.’s new electric pickup truck plant in nearby Haywood County.

Hank Clay, chief of staff for Metropolitan Nashville Public Schools, worried that any move toward eliminating federal funding or oversight could tempt districts to shift money that helps their most vulnerable students, especially when school leaders are dealing with other challenges around teacher pay and school facilities.

“If there’s funding on the table to replace these federal dollars, we would welcome that, but ask that it be in addition to — because our students deserve it,” Clay said.

Matt Hixson, who leads schools in Hawkins County, called infrastructure a “huge concern” and noted that his rural district is staring at a $15 million price tag for roof replacement at two high schools. That cost is borne by local taxpayers.

“The only way we have to fund some of those projects is to stand in front of my peers in the county and say we need more tax money,” he said. “I’m a taxpayer too. I’m not a fan of big taxes.”

Earlier this year, the Tennessee Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations reported that the state needs to invest more than $9 billion in its K-12 education infrastructure over five years, an increase of nearly 9% from an assessment done a year earlier.

Of that amount, about $5.4 billion is needed for renovations and technology improvements, while nearly $3.6 billion is needed to build additions and new schools.

Marta Aldrich is a senior correspondent and covers the statehouse for Chalkbeat Tennessee. Contact her at maldrich@chalkbeat.org.