Sign up for Chalkbeat Tennessee’s free daily newsletter to keep up with statewide education policy and Memphis-Shelby County Schools.

One high school took in 4 feet of water and is expected to be declared a total loss. Other campuses in northeast Tennessee sustained roof, water system, and other damage — including food that spoiled in refrigerators after the power went down. School bus routes have been thrown into disarray by mangled roads and bridges.

Officials across the region are still assessing Hurricane Helene’s damage to schools and their surrounding communities, but a few things are becoming clear: The already massive repair needs for Tennessee school buildings and other public infrastructure are about to grow. And with a long and costly recovery ahead, state leaders will need to rethink some of their top budget priorities — possibly including Gov. Bill Lee’s desire to extend private school vouchers statewide — to figure out how to pay for them.

“I’m not sure when we’ll be back in school,” said Mischelle Simcox, superintendent of Johnson County Schools.

Late last week, her team was trying to figure out how to revamp transportation in a district where 75% of its 2,000 students rely on buses to get to six rural schools.

“Many of our highways are just gone, and a lot of bridges are out,” she said. “We’ve been through blizzards. We’ve been through COVID. But in my 26 years as an educator, I’ve never seen anything like this.”

There is money available. Tennessee’s current spending plan, for instance, includes $144 million for Lee’s universal school voucher proposal — funding that’s sitting unused since the bill stalled in the legislature in April.

The state’s rainy day fund, now projected to reach a record-high $2.15 billion, is another potential source. That money is set aside in case of economic downturns or emergencies. But lawmakers have historically been protective of the pot because it contributes to Tennessee’s good bond rating, which also helps local governments get lower interest rates when borrowing money.

In addition, there may be unclaimed funding from $1.5 billion the legislature allocated this year to give certain tax refunds to businesses, which have until Nov. 30 to submit their claims.

Rep. Mark White, a Memphis Republican and voucher supporter who chairs a House education committee, is ambivalent about which source or sources to tap. But he is adamant that the state should reevaluate its priorities.

“Our first priority now has got to be taking care of our neighbors in East Tennessee and helping them recover from this storm damage,” White said.

“Can we do universal vouchers, too? I don’t know,” he continued. “But East Tennessee has got to be our top focus.”

Eight hard-hit counties due to receive federal aid

The hurricane blew ashore in Florida on Sept. 26, then dumped more than 40 trillion gallons of rain on the Southeast in less than a week, battering inland communities that typically are safe from tropical storms. At least 230 people have died, including 15 Tennesseans, with many people still missing.

Eight mostly rural, mountainous counties suffered the brunt of the record-setting rainfall in East Tennessee — Carter, Cocke, Greene, Hamblen, Hawkins, Johnson, Unicoi, and Washington. They’ve already been approved to receive federal disaster aid, with philanthropic help promised by entities ranging from nonprofit organizations to entertainer Dolly Parton, an East Tennessee native.

The ultimate cost of recovery to state government could exceed $1 billion.

Transportation officials project it will cost hundreds of millions of dollars just to repair state-owned bridges, and they expect months of road closures. For many students, bus detours could lengthen their daily commute by hours.

In Carter County, where Hampton High School flooded, the school board voted in an emergency meeting last week to relocate its 400 students to the district’s central office building, a former school. But with the abandoned campus located in a flood plain and help from insurance providers unlikely for a rebuild, school leaders were preparing for a long, arduous recovery.

Most schools in the region weathered the storms better, but still sustained damage, including roofs to repair, buckled parking lots, and lots of downed trees, debris, and mud to clean up.

Many campuses where electricity and water have been restored are serving as community resource centers, providing food, shelter, and laundry and showering services to displaced families, especially since some schools were already planning closures for fall break.

A group of education and philanthropic leaders have established the Northeast Tennessee School District Disaster Relief Fund, with 100% of the proceeds going to assist school districts hardest hit by Helene.

Tennessee was already behind on school building needs

Before the hurricane hit, Tennessee already had a statewide backlog of school building needs through 2027, estimated to cost nearly $10 billion. It’s part of a $68 billion inventory of public infrastructure needs that also include roads, bridges, utilities, and firehouses, according to the state’s latest assessment.

For local officials seeking to transform their communities through education, keeping up with school upgrades is especially important. A growing body of evidence asserts higher-quality facilities translate into better academic outcomes for vulnerable children, plus higher property values for communities that surround improved school buildings.

Rep. David Hawk, a Greeneville Republican whose district was affected by the floods, has tried for a decade to direct recurring state funds to brick-and-mortar education needs. Helene’s aftermath, he said, further highlights the challenges faced by city and county governments, which mostly use property and sales tax revenues to pay for school facilities.

“Right now in Upper East Tennessee, we’re focused on immediate needs, but our long-term needs will not be a quick fix,” Hawk said. “We’ll be coupling state and federal dollars to achieve what needs to be done. I hope one day we’ll be able to use recurring state dollars to fund the schools and roads and bridges and water and sewer infrastructures that need to be upgraded.

“The needs are everywhere,” Hawk said.

On Tuesday, Tennessee Democrats launched a previously planned“Rocky Top, Not Rocky Roads” campaign aimed at modernizing the state’s transportation systems and relieving traffic congestion amid climate change that’s fueling natural and environmental disasters.

“We have got to stop being so reactive in our state, “ said Sen. Heidi Campbell, of Nashville, while Rep. Ronnie Glynn, of Clarksville, called for “intelligent, sustainable solutions.”

How the storm could shift the voucher debate

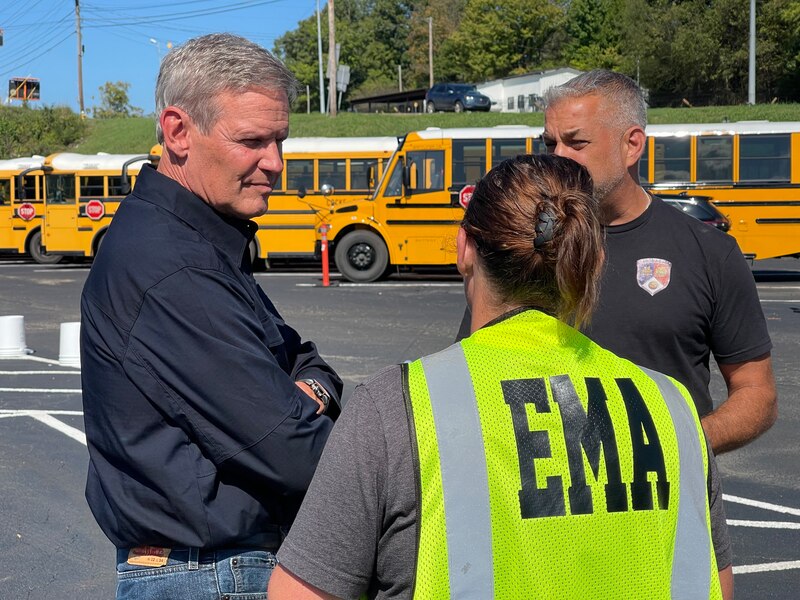

Touring damage in Cocke County last week, the governor said his administration was working on a plan specifically to assist students.

“We’ve got to think outside the box,” Lee said, “not just respond in the way that we know how to respond, but go above and beyond that, recognizing that these kids need to be in school, and they need to be fed, and they need to be educated, and they need all the services that come with that.”

Voucher opponents say thinking outside of the box should include reallocating untapped voucher funding from the current state budget to help storm-ravaged schools.

The $144 million allocation was Lee’s consolation prize after Republican disagreements derailed his universal voucher proposal in legislative committees in April. The conflict stemmed partly from worries that offering school vouchers statewide, regardless of family income, could bust the state’s budget, similar to Arizona’s experience after it pioneered one of the nation’s largest school voucher programs in 2022.

But hours after Tennessee lawmakers adjourned this spring, Lee said money they budgeted for his proposed Education Freedom Scholarship Act showed their “clear intent” to pass universal vouchers next year when the General Assembly reconvenes.

JC Bowman, executive director of Professional Educators of Tennessee and a frequent voucher critic, said “the optics are horrible” to leave such funding in place as Tennesseans toil with a natural disaster. The state’s juvenile justice system, he noted, is also under intense statewide strain this fall because of hundreds of school threats, mostly on social media, with some local officials pleading for more juvenile detention space.

“We don’t have an obligation to fund private schools under our state constitution, but we do have an obligation to fund public schools,” Bowman said. “If the choice is between vouchers and rebuilding our state and keeping our kids safe, there’s no really no choice.”

“We’ve been through blizzards. We’ve been through COVID. But in my 26 years as an educator, I’ve never seen anything like this.”

— Mischelle Simcox, superintendent, Johnson County Schools.

White, a longtime lawmaker from Memphis, agrees the legislature should revisit its financial priorities, though he’s not ready to identify what should stay and what should go.

His district is on the opposite end of the state from Helene’s destruction but lies along the New Madrid Fault seismic zone, a source of tremors and historic earthquakes affecting seven states.

“If Memphis had an earthquake, I would hope the state’s No. 1 priority would be helping Shelby County and any other counties affected in our region of the state,” he said.

“We’re all Tennesseans.”

Marta Aldrich is a senior correspondent and covers the statehouse for Chalkbeat Tennessee. Contact her at maldrich@chalkbeat.org.