Sign up for Chalkbeat Tennessee’s free newsletter to keep up with statewide education policy and Memphis-Shelby County Schools.

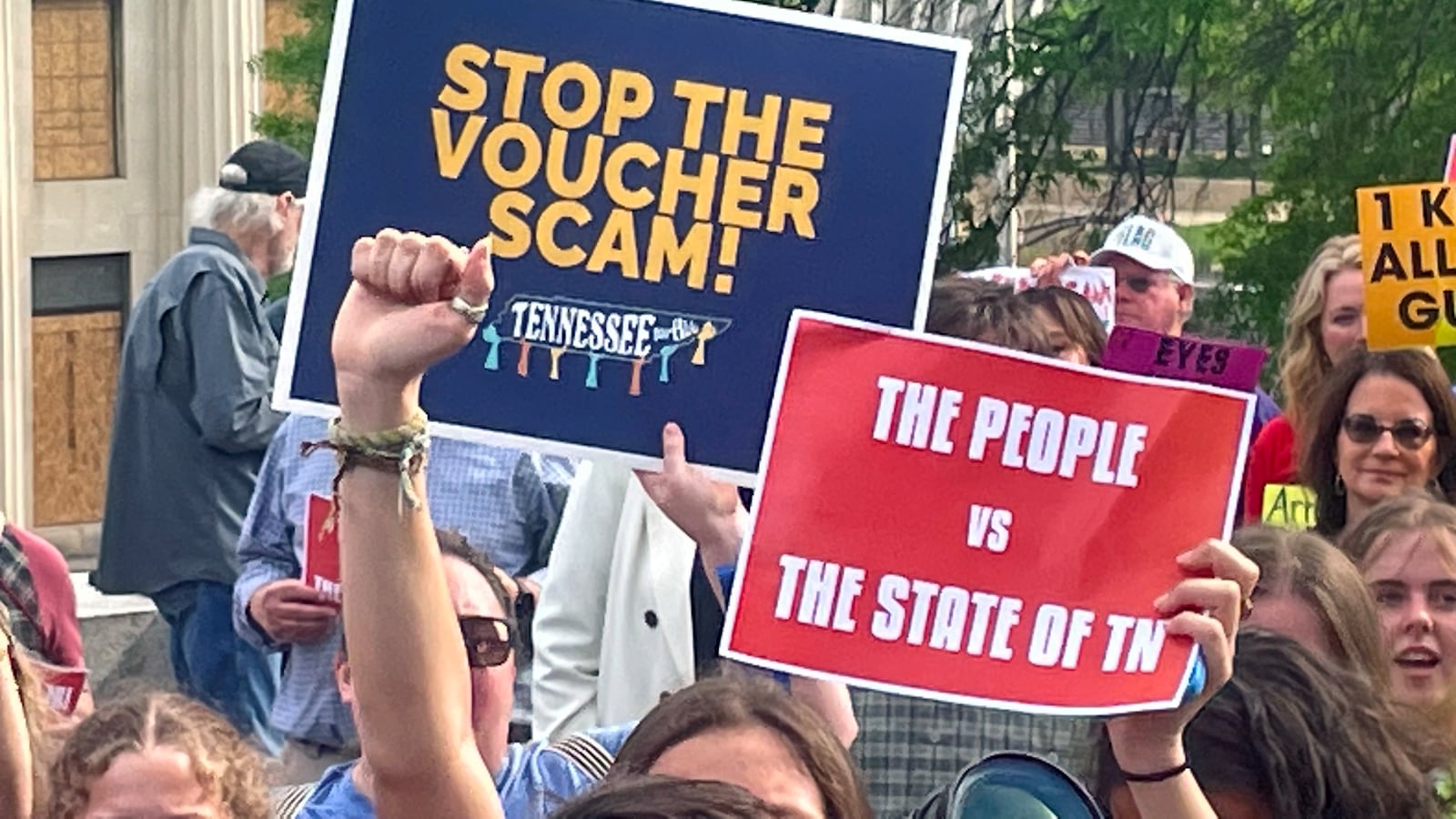

After the collapse of his statewide private school voucher proposal last year, Gov. Bill Lee is back with a similar plan to try to convince lawmakers that Tennessee students need another taxpayer-funded alternative to traditional public schools.

But while his new Education Freedom Act enjoys unified support among Republican leaders in both legislative chambers — a major difference from this time last year — it’s also generating many of the same concerns that contributed to the 2024 bill’s demise.

Complicating matters further are sagging tax collections that will make it harder to launch and sustain expensive new initiatives. Also, an existing smaller “pilot” voucher program remains under-enrolled in its third year, and the students in it are generally performing below their public school counterparts.

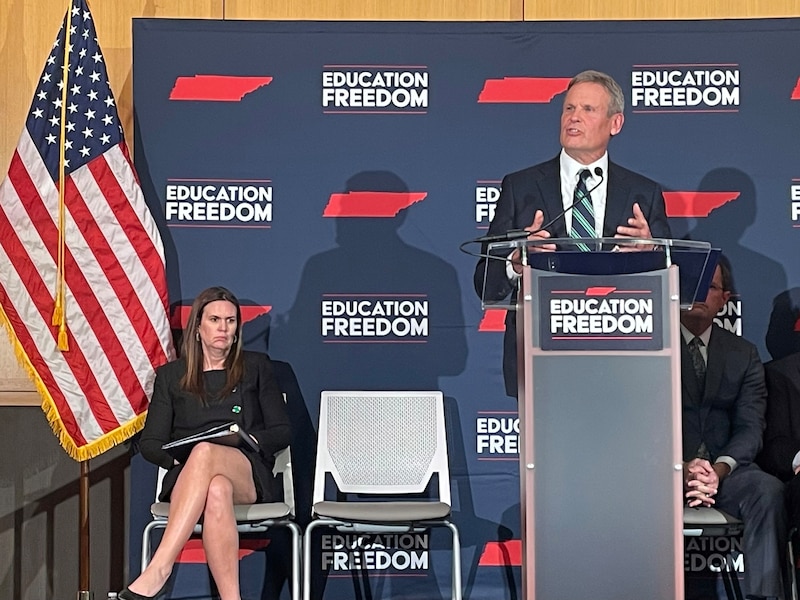

Lee, who is term-limited, has made the voucher policy one of his top objectives since taking office in 2019, and recently hinted that he may call a special legislative session to prioritize his proposal before lawmakers take up other business. The legislature would need to pass his bill in early 2025 to give his administration enough time to launch a universal program this summer, before the upcoming school year.

A recent poll conducted by Vanderbilt University shows Tennessee voters are mostly split over school vouchers.

Lee is trying to build public support, though, through statewide TV ads featuring him and paid for by the pro-voucher American Federation for Children, as well as radio ads paid for by Americans for Prosperity, a conservative political network founded by the billionaire Koch brothers of Kansas.

Standing between the governor and the realization of his universal voucher program in Tennessee are three big issues:

Long-term funding uncertainty for public schools

State officials have estimated that about half of voucher recipients in the program’s first year would come from public schools, with the rest already enrolled in private schools or new students entering kindergarten.

To quell anxiety about the financial impact on public schools, Lee’s legislation includes a “hold harmless” provision that essentially would reimburse school districts for any funding they stand to lose when a student leaves to take a voucher and go to a private school.

Also, voucher money would not come out of the state’s existing funding formula for public schools, but rather from a separate line item in the budget that already has $144 million in untapped funds appropriated by the legislature last year.

But laws — and budgets — can change from year to year, and put those pledges at risk.

Under the legislation, it’s unclear how Lee intends to pay for reimbursements to public schools for the first year, and in future years, especially since participation is expected to grow.

A future governor and legislature could take away the reimbursements, particularly if overall tax collections continue to decline under Lee’s 2024 initiative to reduce corporate and business taxes in Tennessee.

At the same time, the state would be obligated to fund the new statewide education program for the foreseeable future. With Lee’s plan to add 5,000 vouchers each year, the program could direct up to $862 million in taxpayer funding toward private education costs during the first five years, according to an analysis by Ed Trust of Tennessee.

And because of the bill’s loose restrictions on who could receive the new vouchers, a large number of the program’s recipients are expected to come from families who already send, or plan to send, their children to private schools.

In Arkansas, which approved universal vouchers in 2023 under Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders, more than 80% of last year’s enrollees had not attended public schools the previous year.

In an effort to garner more support for the Education Freedom Act, Tennessee’s bill includes several financial benefits for public schools.

One would redirect 80% of sports wagering tax revenue now going to pay for college scholarships to instead help fund school building and maintenance projects across the state, especially for emergencies and for rural districts in counties designated as distressed or at risk.

But that’s only about $70 million annually and wouldn’t go far toward addressing the state’s $9.8 billion backlog of school facility needs. (Building a single elementary school can cost up to $60 million these days, while a new high school can cost significantly more.)

A second enticement would give every public school teacher a one-time $2,000 bonus. Many teachers who would be eligible to receive the money dismiss that proposal as a diversion tactic and believe the larger goal of Republican leaders is to eventually defund public schools.

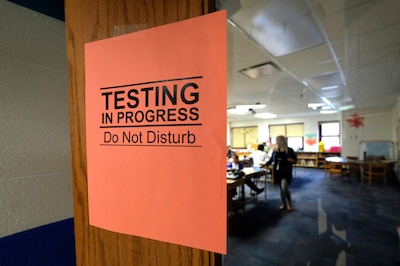

Uneven standards for testing and accountability

The bill would require the new voucher recipients in grades 3-11 to take annual state or national standardized achievement tests to track the program’s effectiveness.

That’s a departure from the state’s existing Education Savings Account program that requires recipients to take the same state tests as their public school counterparts in math and English language arts, which provides an apples-to-apples comparison of educational outcomes.

The testing issue creates a quandary for Republicans.

Holding government accountable for how it spends taxpayer money is a conservative principle. But private schools are less likely to participate in a voucher program if they’re required to administer any state tests that are based on state-approved academic standards.

With Lee’s new proposal, supporters now say that national tests are good enough to gauge how students who take voucher money are doing.

Detractors say that sets uneven standards of accountability for different groups of students whose education is being funded with the same taxpayer money.

To some extent, the existing pilot voucher program already has a differing measuring stick. Participating private schools aren’t evaluated like public schools are under the state’s new A-F school grading system to help parents gauge their effectiveness. Moreover, in issuing grades to public schools, Lee’s administration has elevated the importance of academic proficiency based on state test results. But for private schools receiving public funding through education savings accounts, it has mostly touted surveys showing high parental satisfaction in the program.

Lee has repeatedly said his priority is to give parents more choices and control over their children’s education.

Which students would be included, and excluded?

Voucher supporters use the language of “school choice” to promote the policy.

But private schools get to choose the students they enroll, not the other way around — potentially reinforcing discriminatory practices and widening educational disparities between affluent students and historically underserved groups.

Lee’s proposal, for example, includes no guarantees of services and accommodations for students with disabilities.

Unlike with public schools, students who attend private schools are not protected by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, which guarantees children with disabilities access to a free and appropriate education. Essentially, the federal law requires public schools to give those students specialized support and services determined collaboratively by school leaders and parents.

Lee’s proposal has no anti-discrimination language that would prevent schools from selectively admitting, or expelling, students based on criteria that may include color, disability, test scores, family income, religious affiliation, national origin, or sexual orientation.

State laws typically include anti-discrimination language regarding eligibility for education programs. Even Lee’s 2019 Education Savings Account law, which created vouchers for some students in Memphis and Nashville, and later in Chattanooga, requires participating private schools to certify that they will “not discriminate against participating students or applicants on the basis of race, color, or national origin.”

The newest legislation isn’t so broad in its protections.

To satisfy far-right conservatives, for example, it specifically bars students who can’t show that they’re in the United States legally from participating in the proposed program. That would violate federal law and could set the stage for another protracted and expensive legal challenge to Tennessee voucher law.

Already, students of color, kids from low-income families, and those with disabilities are often left out of school choice programs due to the locations and supply of private schools, transportation challenges, confusing admission policies, and the high cost of tuition, national data shows.

Without the non-discrimination language, Lee’s voucher policy as proposed raises the risk not only that Tennessee’s schools will become more racially and economically segregated, but also that tens of millions of taxpayer dollars could flow to so-called segregation academies that were established in the 1960s and 1970s for white children during the desegregation movement.

Some of those schools still exist, although Chalkbeat has not analyzed which private schools in Tennessee fit that definition.

North Carolina built its school voucher program the same way that Lee has advocated for Tennessee. When it launched in 2014, the program was only for low-income families, but in 2023, state lawmakers expanded eligibility to students of all income levels and those already attending private school.

According to reporting by ProPublica, 39 schools that it identified as likely segregation academies have received taxpayer money from North Carolina’s voucher program.

You can read Tennessee’s voucher bill here and track its movement in the legislature here.

Correction: A previous version of this story said Americans for Prosperity paid for TV and radio ads promoting Gov. Lee’s Education Freedom Act. The radio ads were paid for by Americans for Prosperity, while the TV ad was paid for by American Federation for Children, another pro-voucher group.

Marta Aldrich is a senior correspondent and covers the statehouse for Chalkbeat Tennessee. Contact her at maldrich@chalkbeat.org.