In 2008, The Atlantic ran a story headlined “First, Kill All the School Boards.” The problem with American education, the piece concluded, was its structure: thousands of disparate boards, each influenced by local politics and teachers unions but subject to little oversight.

It was emblematic of a mindset that held real sway over the last two decades, with big city school districts, including New York and Chicago, shifting control to the mayor. In dozens of other cases, states took over school districts deemed low performing.

Now, a new national study casts significant doubt on the idea that states, at least, are better positioned to run schools than locally elected officials. Overall, researchers found little evidence that districts see test scores rise as a result of being taken over. If anything, state control had slightly negative effects on students.

“Maybe school boards are the least worst option that we have,” said Beth Schueler, a professor at the University of Virginia and one of the study authors.

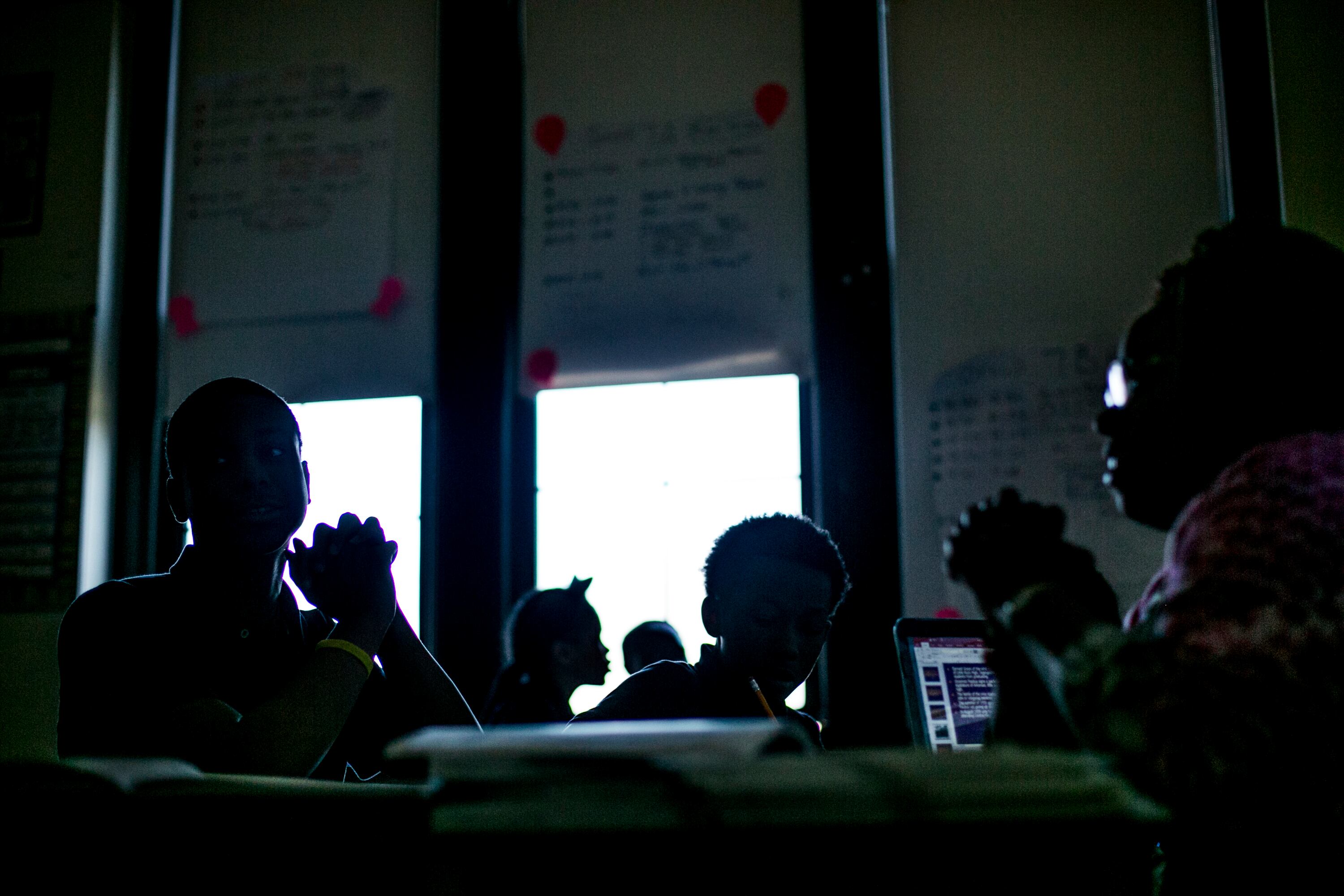

The paper is the most comprehensive accounting to date of a strategy that has appealed to policymakers in many states but also brought fierce blowback. The study doesn’t suggest that takeovers never succeed on academic grounds — there are clear examples where they have. But the successes appear to be more exception than rule, and the uneven academic results bring into sharp relief the costs of state takeover: the loss of democratic institutions, disproportionately in Black communities.

“These policies are very harmful to communities in terms of their political power,” said Domingo Morel, a Rutgers University political scientist who has studied and criticized state takeovers. “And then what the state says is going to improve — this research shows it’s not doing that either.”

The new study focuses on the 35 school districts from across the country that were taken over by states between 2011 and 2016. These takeovers often happened in small cities and the vast majority of affected students were Black or Hispanic and from low-income families.

“At some point you just have to go in a new direction,” an Arkansas state board of education member said in 2015 after voting to take over Little Rock’s schools.

To find out what happened next, Schueler and coauthor Joshua Bleiberg of Brown University used national test score data to compare districts that were taken over to seemingly similar districts in the same state that retained local control.

In the first few years of the takeover, the schools generally saw dips in English test scores. By year four, there was no effect one way or the other. In math, there were no clear effects at all.

“The punchline is, we really don’t see evidence that takeover is benefitting student outcomes, at least in the short term,” said Schueler.

Some places — including Camden, New Jersey and Lawrence, Massachusetts — did see improvements in the wake of takeover. (In general, takeovers were most likely to succeed in places that had very low test scores to begin with.) But just as many districts — like East St. Louis, Illinois and Chester Upland, Pennsylvania — saw their academic records get worse, relative to other schools in the states.

One reason results might have diverged so much is that there’s no single playbook for what happens after a state takes control from an elected school board. It’s also possible that state takeovers don’t typically improve student achievement simply because they often don’t lead to meaningful changes in how schools are run. Districts generally didn’t see much difference in their per-student spending, class sizes, or the number of charter schools.

“Why I think the results are so mixed in the study — the takeover in and of itself is a black box,” said Jonathan Collins, an education professor at Brown University. “It can mean anything.”

The study doesn’t examine other potential benefits of takeovers, including the pressure they might put on other districts to get better or nonacademic improvements, like stronger financial management.

One city that did see academic success with a state takeover was New Orleans, where the process included a dramatic expansion of charter schools and a big increase in spending on schools. A forthcoming study found this combination of reforms increased high school graduation rates by 9-13 percentage points and college completion by 2-3 points.

But even takeovers that bring academic improvements have costs, argues Morel of Rutgers. For instance, both New Orleans and Camden saw declines in the number of teachers of color. Morel worries that taking away elected boards weakens communities’ political power.

“The argument that somehow we’re going to make it less political by eroding the mechanisms of democracy is something that we only consider for majority communities of color,” he said. “Why don’t we learn about those districts that did improve and think about: what is it that’s happening there that we might try to replicate without taking over?”

Some places are moving away from takeovers. Detroit, New Orleans, Newark, Philadelphia, and St. Louis have returned schools to local control in recent years. Ohio is considering a bill to make it easier for districts to end a takeover, and Indiana recently scrapped its law allowing for the takeover of individual schools. “Past interventions and penalties have not resulted in many successes, as we all know,” Tony Cook, an Indiana state representative, said earlier this year.

Elsewhere, takeover efforts have continued. Texas has sought to take control over Houston, the country’s fifth largest district, though a court has blocked the move at least temporarily.

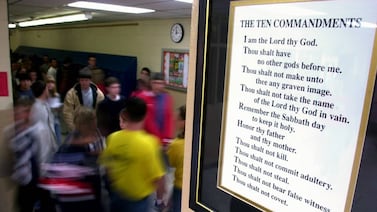

Perhaps the most high-profile recent state takeover has come in Providence, Rhode Island. “Very little visible student learning was going on in the majority of classrooms and schools we visited,” a 2019 Johns Hopkins report that precipitated the takeover concluded. “School culture is broken, and safety is a daily concern for students and teachers.”

And yet change has proven challenging to come by. The superintendent chosen to turn the district around just resigned. (An interim replacement was named Tuesday.) A turnaround blueprint released last year was notably thin on specific ideas. The state had made little apparent progress in negotiating a new teachers contract, a key priority.

“We’ve seen a lot of public blows being dished in both directions blaming the lack of progress on the contract on the opposing parties,” said Collins, who sits on a committee at Brown that provides philanthropic funding to Providence schools.

In an interview, Rhode Island state commissioner Angélica Infante-Green said there have been meaningful improvements in Providence, including a shrinking number of teacher vacancies and the purchase of a district-wide K-8 curriculum. The city has also been credited as one of the few urban districts to open its school buildings last fall during the pandemic.

“I think that we’re actually in a good place,” said Infante-Green. “Everybody is anxious right now because the superintendent is gone, but turnaround work is more than just about one person.”

She acknowledged, though, the difficulties of losing the superintendent and struggling to negotiate a new teachers contract.

“Moving the needle is hard,” she said.