Sign up for Chalkbeat’s free weekly newsletter to keep up with how education is changing across the U.S.

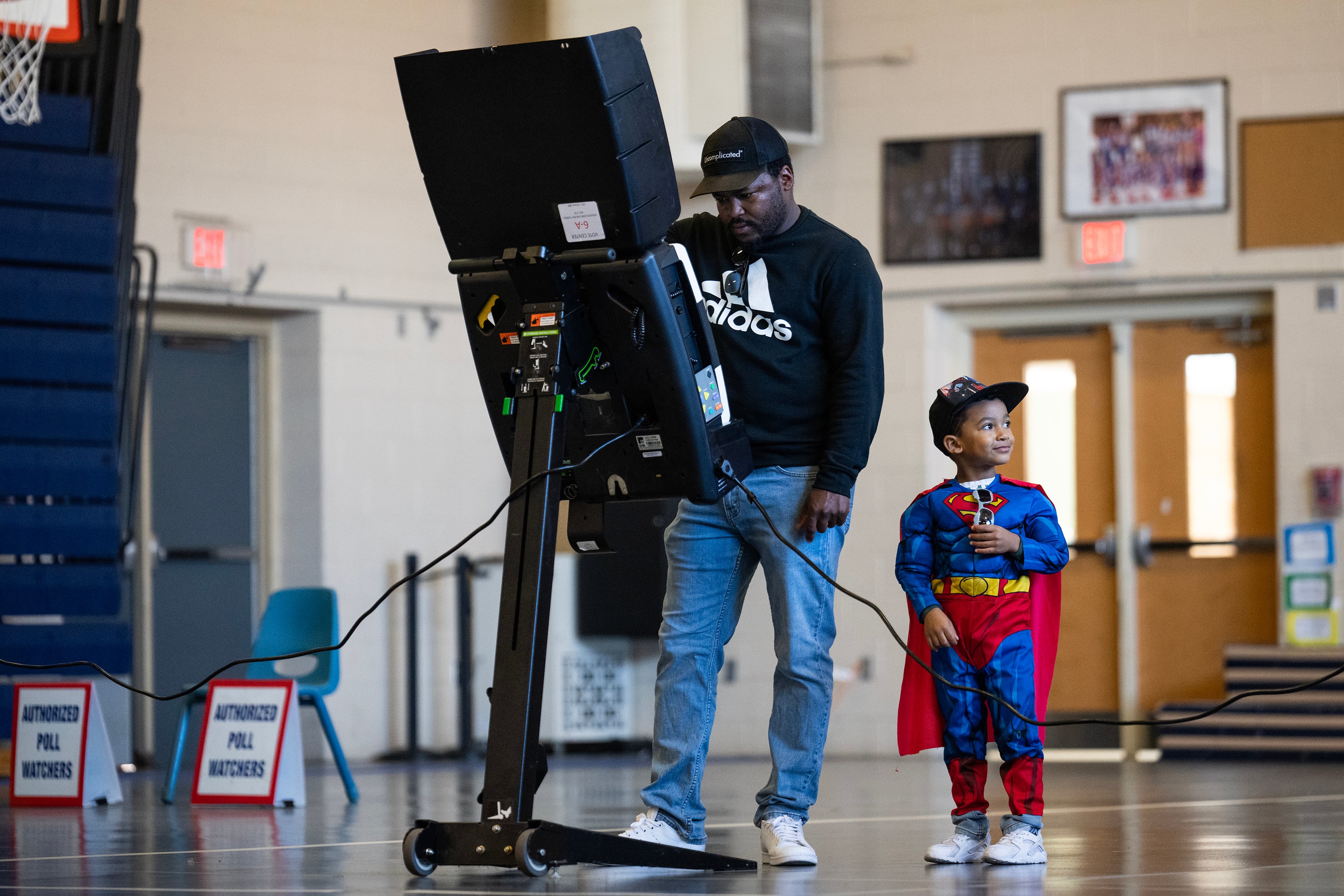

The decisions voters made Tuesday will set the course of education policy for the next four years and perhaps for far longer.

Former President Donald Trump, the Republican candidate for president, has won a second term. He has pledged to get rid of the U.S. Department of Education, cut funding for “woke” schools, roll back new protections for LGBTQ students, and expand school choice. Trump also has pledged to carry out a massive deportation operation that could have significant impacts on schools serving large immigrant communities.

Vice President Kamala Harris, the Democratic candidate, cast herself as the defender of public education. One of her first stops after she announced her candidacy was at the convention of the American Federation of Teachers. She selected a former teacher, Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz, as her running mate.

She focused her campaign on policies such as affordable child care and an expanded child tax credit that could help alleviate child poverty and take some of the burden off K-12 schools. She also promised to expand apprenticeships and make college more affordable.

Political observers have said either candidate’s education agenda — including who ends up serving as education secretary — would be shaped by who controls Congress. Republicans are projected to take control of the U.S. Senate, while control of the House has not been settled.

As always, state and local elections could have a more immediate impact on K-12 education. Voters also chose school board members in hundreds of districts, including in Chicago as part of a transition away from mayoral control. They also weighed in on state superintendents of education, school choice ballot measures, and the meaning of a high school diploma.

We’ll have much more on what Trump’s election means for schools and children. For now, here are some of the education races we have been watching around the country.

An extremist Republican loses bid for top education post in North Carolina

In the high-profile contest for North Carolina’s superintendent of public instruction, Democrat Mo Green beat Republican Michele Morrow.

Morrow’s many controversial statements attracted national attention to the race. She participated in the march on the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, and accused some teachers of being “groomers.” She homeschooled her children for part of their education and referred to public schools as “indoctrination centers” on the campaign trail. Morrow also called for the execution of prominent Democrats, including former President Barack Obama — she later called it a joke.

Green is the former superintendent of Guilford County Schools, one of the largest districts in North Carolina, who also held leadership roles in Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools. He described the race as a fight for the “soul of public education,” and said Morrow’s extremist rhetoric shouldn’t be normalized.

In North Dakota, incumbent state superintendent Kirsten Baesler handily beat Jason Heitkamp, a former state senator, to secure a fourth term. The race is nonpartisan, but both candidates are Republicans.

Notably, Baesler did not win the support of her state’s Republican party in the primary. The party instead backed a home schooling proponent who wanted to put the Ten Commandments in public schools, but that candidate ultimately didn’t get enough votes to advance.

Baesler has said the state’s Republican delegation is out of touch on education and overly focused on ideological issues that don’t have much effect on classroom instruction.

In Montana, Republican Susie Hedalen will succeed outgoing Superintendent Elsie Arntzen, who’s hit her eight-year term limit. She bested Democrat Shannon O’Brien, a state senator who advised former Gov. Steve Bullock on education policy

Hedalen is the vice chair of the state’s board of education and heads Montana’s Townsend School District. She formerly served as a deputy under Arntzen, who faced criticism for how her office oversaw spending and implemented education laws.

In Florida, school board elections remain non-partisan

A proposal to require school board elections to become partisan did not meet the 60% threshold it needed to amend Florida’s constitution, despite getting the support of 55% of voters. The proposed amendment would have mandated school board candidates to have their political party listed by their name on the general election ballot.

According to Ballotpedia, more than 90% of school boards are elected without any party labels attached to candidates. In recent years, however, more states and school districts have discussed moving to a partisan election system. Supporters argue that the new system will provide more transparency regarding the candidates’ political positions, while those opposed to it say it could bring about more polarization and political conflict.

Florida held partisan school board elections before a major electoral reform in 2000.

Voters reject school choice at the ballot

Vouchers and educational savings accounts have gained momentum in legislatures across the country, but voters in three states appear wary of spending public dollars on private schools.

Voters in Colorado were rejecting an effort to enshrine the right to school choice in the state constitution. The ballot measure would not have created or funded a voucher program. Still, opponents feared it would open the door to vouchers in this Democratic-dominated state.

Colorado has a robust charter sector, but Democratic legislators have blocked efforts to introduce private school choice or give public money to home schooling families. In unofficial returns, more than half of voters said no. The constitutional amendment would have needed at least 55% of the vote to pass.

In Kentucky, voters soundly rejected a proposed amendment to the state’s constitution that would have allowed public funding for students in non-public institutions. The proposed amendment proposal was placed on the ballot by Republican lawmakers to clear the way for a voucher program. Democratic Gov. Andy Beshear and the state teachers union opposed the amendment.

Former President Donald Trump, the Republican candidate and a supporter of school choice measures, won the state by a large margin, showing that a large number of Republican voters rejected one of his main education policy proposals.

In Nebraska, voters repealed a new law that would have directed $10 million of public money toward private school vouchers. The law established a partnership between the state and the nonprofit Opportunity Scholarships of Nebraska, directing public money to fund scholarships provided by the organization to low-income students.

The state legislature approved the law in April, with strong support from conservative politicians. Teachers unions opposed the scholarship program and pushed for a repeal to appear on the ballot. Their main argument is that the program would take away funding from public institutions.

The voucher repeal passed by a wide margin. Voucher proponents vowed to keep fighting.

Massachusetts votes to get rid of high school exit exam requirement

In yet another sign of the changing attitudes around what it should take to graduate from high school, Massachusetts residents voted solidly in favor of ditching the state’s required exit exam.

Right now, Massachusetts students have to pass a 10th grade math, science, and English test to get their diploma. Going forward, students will instead have to show they’ve mastered state standards in those subjects by completing certain coursework. School districts will make that call, likely with the state board of education weighing in on what it takes to demonstrate mastery.

The state’s largest teachers union led the campaign to repeal the exit exam requirement, arguing it disadvantages students with disabilities, students learning English, and students from low-income families. Graduation exams generally don’t increase academic achievement, research has found, and they can increase high school dropout rates.

Massachusetts’ governor and secretary of education both opposed getting rid of the test as a graduation requirement, saying the exams help set a uniform and high standard.

Keri Rodrigues, president of the National Parents Union, who lives in Massachusetts, said getting rid of the test would be a “disaster” and lead to some districts setting a low bar with the excuse that children who grow up in poverty just can’t do well in school.

“We don’t like the story that the data tells us,” she said, “that we’re not doing an adequate job preparing our children for adulthood.”

As of last school year, Massachusetts was one of only eight states that still required high schoolers to pass an exit exam to graduate. Several states have ditched the requirement in recent years, and others are moving in that direction. New York officials, for example, also proposed getting rid of the requirement that students pass the state’s Regents exams to graduate as part of a broader diploma overhaul.

Chicago elects first school board members

Chicago voters appear likely to elect a politically mixed school board as the nation’s fourth-largest school district begins a transition away from mayoral control. Unofficial results showed four teachers union-backed candidates, three pro-school choice candidates, and three independent candidates either winning or holding leads.

The elected board members will serve alongside mayoral appointees until 2026, when all members will be chosen by the voters.

The election comes at a time of political turmoil, as Mayor Brandon Johnson, a former teachers union organizer, has tried to assert his authority and stave off cuts to schools with a controversial plan to use loans to cover pension obligations.

The appointed members of the board recently resigned en masse, and some of their replacements may be replaced again once the election results are clear. That means that an entirely new board with no experienced members will be charged with tackling major challenges, including a looming budget deficit, negotiations for a new teachers contract, the future of school choice, and the district’s relationship with the city.

Both the Chicago Teachers Union and pro-school choice groups have spent heavily in the race in an effort to influence the outcome.

Union-backed candidates leading in Los Angeles

Supporters of charter schools had hoped to pick up at least one seat on the Los Angeles Unified School District board as that body faces a major leadership transition. But in early returns, candidates backed by the teachers union were ahead, the Los Angeles Times reported.

Long-serving members of the board President Jackie Goldberg and George McKenna are retiring. Members backed by the teachers union took control in 2022. Since then, charter schools have faced less favorable policies while grappling with problems like declining enrollment.

Los Angeles is the nation’s second-largest school district and the largest governed by an elected school board. Technically there are four open seats on the seven-member board, but one of the races was decided in March when incumbent Tanya Ortiz Franklin, a supporter of charter schools, won her primary with more than 50% of the vote.

The most watched race is in District 3, where Dan Chang, a teacher and charter supporter, tried to unseat incumbent Scott Schmerelson, who had the backing of the teachers union.

Schmerelson, who has served two terms on the school board, was favored to win the race and was ahead in initial returns. Schmerelson has been a reliable vote for more charter oversight.

Chang had said that if he were successful, he would repeal a controversial policy that limits charter schools’ ability to use district buildings. Sharing space has been critical to charter school growth not only in Los Angeles but in other cities as well.

In another race, a candidate backed by the teachers union had a strong lead over one backed by the support staff union. In the final open seat, Sherlett Hendy Newbill could bring a more independent voice. The teachers union had backed her primary opponent before antisemitic social media posts effectively ended his candidacy, and she received very little financial support from the union.

Elsewhere in California, candidates backed by conservative parents’ rights groups and teachers unions are battling for control of school boards in elections that focus more on control over curriculum and the erosion of policies to protect racial equity and LGBTQ rights.

Erica Meltzer is Chalkbeat’s national editor based in Colorado. Contact Erica at emeltzer@chalkbeat.org.

Kalyn Belsha is a senior national education reporter based in Chicago. Contact her at kbelsha@chalkbeat.org.

Wellington Soares is Chalkbeat’s national education reporting intern based in New York City. Contact Wellington at wsoares@chalkbeat.org.