A Denver charter elementary school focused on fully including students with disabilities will close at the end of this school year due to staffing and academic challenges school leaders say were exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The board of directors of REACH Charter School voted last month to close the school after learning that Denver Public Schools staff was going to recommend the school board not renew its charter with REACH — which would have been the first such recommendation in nearly a decade. The REACH board decided to surrender its charter instead.

Principal Jason Marsh, a former special education teacher who helped found the school seven years ago, said REACH weighed what it would take to fight the district’s recommendation against giving families as much time as possible to find new schools for their children. The Denver school board voted Thursday to accept REACH’s charter surrender.

“We thought this would be a way we would be able to afford more time to work on student transition and getting our staff transitioned as well,” Marsh said.

Parent Mariam Arab, whose 3-year-old son has a hearing disability, is worried about finding a school that provides the same support and family environment as REACH.

“He loves his teachers,” Arab said of her son, who started preschool at REACH last spring. “I just hope the school we find later has what they have, but I doubt it.”

REACH will be the eleventh Denver charter school to close in the past four years. Many of the charters closed due to low enrollment, an issue affecting the entire district that will likely lead to more school closures.

REACH has also suffered from declining enrollment. It has just 82 students in preschool through fifth grade right now, Marsh said, down from 140 two years ago.

The recommendation to not renew REACH’s charter stemmed partly from a school visit conducted by district staff in November. While teachers were observed treating students respectfully and providing emotional support, the academic instruction was not always rigorous or high quality, according to a report obtained by Chalkbeat. The report notes “significant gaps” in teaching grade-level content and providing extra help to students who need it.

That wasn’t the experience of Jaclyn Miller and her 8-year-old son, who has attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and anxiety. When he started at REACH in kindergarten, he would get so overwhelmed in the classroom that his behavior would become explosive. Now in third grade, he’s learned to advocate for himself and his needs, and he’s reading on grade level.

“They just saw him for who he is,” Miller said of the REACH staff. “That’s what’s so powerful about REACH. … They know what each kid’s unique gifts are and where they need support, and I think that really empowers the kids to grow there.”

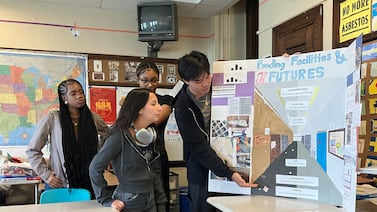

REACH’s model is unique in Denver Public Schools in that one-third of its students have special education plans and two-thirds do not. All students are taught in the same classrooms, a practice known as inclusion.

Though Denver Public Schools has said it wants to become a nationwide model for inclusive practices, many Denver students with disabilities are still served in separate classrooms at least some of the time. In accepting REACH’s charter surrender, Denver school board members said the district should learn from the parts of REACH’s model that worked well.

Several said it pained them to see the school close.

“We must make sure — not just as a board, not just as a superintendent, not just as staff, but as community partners as well — that schools that are serving vulnerable communities are able to keep their doors open,” said board member Michelle Quattlebaum.

Marsh said REACH’s model made it difficult to find qualified teachers who believe in the mission — a challenge that was exacerbated by pandemic-era staffing shortages. A schoolwide instructional leader hired in the summer of 2020 left after only one year, the district report notes. A new instructional leader hired this year lasted only a few weeks. Marsh said he was unable to fill a third grade teacher position until the day before school started in August.

REACH also struggled these past two years with the frequent back-and-forth between in-person and remote learning, some of which was driven by districtwide decisions and some of which was in response to COVID outbreaks at the school. When district staff visited REACH to evaluate the school for its charter renewal, students had just returned from a stretch of remote learning, which many students with disabilities found difficult, Marsh said.

“REACH was never intended to be a remote learning program,” he said. “It was very challenging for our impacted young students to be online and then transitioning them back to in-person learning and being able to maintain the high level of rigor. It was very challenging.”

REACH board President Jonathan Leinheardt, whose son attended from first through fifth grade, said it was a difficult decision to surrender the school’s charter. But he said the school is committed to doing all it can to help current families find new schools, including hosting information sessions about the district’s open enrollment process, which starts Friday.

Miller said her 8-year-old son, who formed deep bonds at REACH and has had the same group of friends since kindergarten, is anxious about starting over in a new place.

“I asked him, ‘What is the most important thing you want out of a school?’ and he said, ‘I want my teachers to understand me and I want my friends or my classmates to understand me,’” she said. “He’s very nervous about not being able to find that again.”