Sign up for Chalkbeat Colorado’s free daily newsletter to get the latest reporting from us, plus curated news from other Colorado outlets, delivered to your inbox.

Phil Chen spent weeks this winter touring Denver elementary schools. He knew what he was looking for: a school that most closely resembled his daughter’s current school, Palmer Elementary, which will close in June.

Chen’s daughter got into the family’s top choice for next year. But Chen isn’t necessarily happy.

“Yes, we were successful in getting into our first-choice school. And that’s great,” Chen said.

But, he added, “I’d rather we be at Palmer.”

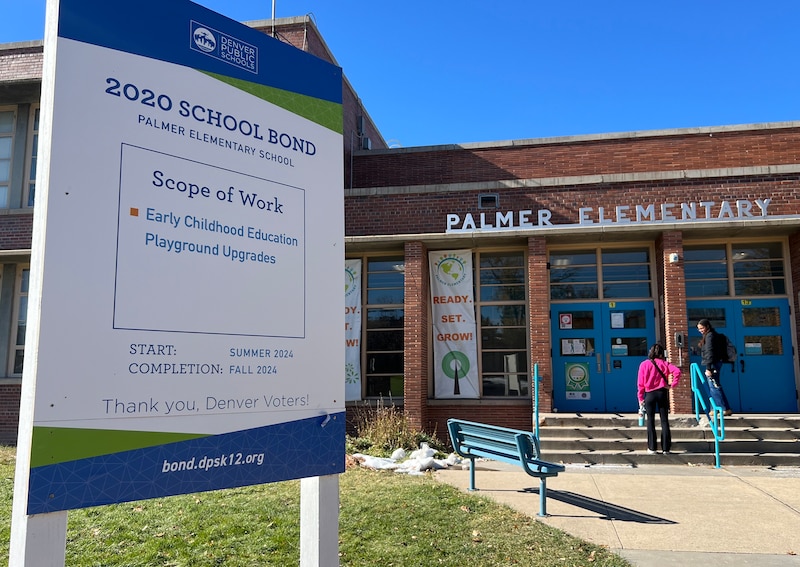

Palmer is one of 10 Denver schools that will close or partially close at the end of the school year due to declining enrollment, mostly driven by lower birth rates and gentrification.

But Denver Public Schools took a different approach to finding new schools for displaced students in this latest round of closures. Instead of matching each closing school with a receiving school, the district gave students multiple options and top preference at the school of their choice, leapfrogging even siblings and the children of teachers.

“It felt like an important offering we could make to families because we were disrupting their experience,” said Andrew Huber, executive director of enrollment and campus planning for DPS.

Although many parents like Chen have mixed feelings, district officials are hailing it as a success. Nearly all students got into their first-choice schools. A Chalkbeat analysis found other notable trends: Half of the displaced students will go to higher-performing schools, and a significant number are moving from district-run schools to charter schools.

School closures are controversial for many reasons, including concerns that the affected students will suffer social and academic harm. Nearly all studies show that the quality of the school where displaced students end up matters.

Of the 1,106 Denver students whose schools are closing, 92% participated in the school choice process this winter, according to district data. An unprecedented 98% of those students got into their first-choice school. Typically, fewer than 85% of students get into their top choice.

A deeper look at the data shows:

- 20% of students from the closing schools will attend charter schools next year. All 10 of the closing schools are run by the district. Charter schools are authorized by the district and funded by public dollars but run by independent nonprofit organizations.

- Rocky Mountain Prep, a homegrown charter network with 11 schools in Denver, will enroll the most students from the closing schools next year. Nearly 12% of students who participated in school choice chose a Rocky Mountain Prep school.

- About 50% of students at the closing schools will attend a school next year with a higher state rating. In general, that means students will attend a school that performs better academically since state ratings are largely based on standardized test scores.

- Only 4% of students at the closing schools will attend a school next year with a lower state rating. The rest will attend a school with the same rating.

New enrollment zones nudge students to higher-rated schools

That half of the students from the closing schools will attend better-rated schools next year wasn’t surprising to school board President Carrie Olson.

Low enrollment and low academic performance are often linked. Because Denver funds its schools per student, when a school’s enrollment dips, so does its funding. That makes it harder for the school to afford academic interventions, which can make it unpopular with both families and teachers.

“When a school is declining in enrollment, it loses resources and it loses teachers,” said Olson, who was a DPS teacher for 33 years before being elected to the board. In some cases, she said, high-performing teachers at schools with shrinking enrollment think, “Well, maybe I’ll apply somewhere else because this school is going to close anyway.”

But academic performance wasn’t the board’s main reason for closing schools this year. A decade ago, it was. Back then, the board had a policy that called for the district to close schools with a history of low test scores. The policy was highly controversial, and the board only used it to close one school before abandoning the strategy due to pushback.

That DPS has managed to shift students from lower-performing to higher-performing schools without explicitly setting out to do so is cause for celebration, said Van Schoales, who for years ran a now-defunct organization called A Plus Colorado that advocated for school reform.

While past DPS superintendents and school boards supported school reform and the “portfolio model” — in which families are given the power to choose a school, and successful schools replicate while struggling schools close — this board and superintendent do not.

“The last I checked, the school board and the superintendent said this strategy was a total disaster,” Schoales said of the portfolio model. “And yet they’re doing it better than the last folks who were supposedly focused on doing this well.”

Huber said the district nudged families toward higher-rated schools by creating new “enrollment zones” around the closing schools. Enrollment zones are big boundaries that contain several schools. Families that live in a zone are guaranteed a seat at one of the schools and asked to choose between them. By drawing the new zones to include higher-performing schools, the district intentionally gave families at the closing schools several top-rated options, Huber said.

And the data shows families took advantage. The top choice among families at red-rated Columbian Elementary was green-rated Beach Court Elementary. The top choice at yellow-rated Schmitt Elementary was green-rated Asbury Elementary.

“The superintendent and his team were hoping it would help facilitate access to high-performing schools for families while understanding families’ choices are their own,” Huber said.

He emphasized that there are lots of reasons why families choose a particular school, and academic performance is just one factor. Huber said the choices of the 4% of students who will attend a lower-rated school next year are “just as valid” as the choices of the 50% of students who will attend a higher-rated school.

Some families made unexpected choices

In some cases, families made choices the district wasn’t expecting, Huber said.

Only one of the new or expanded enrollment zones — the zone around the closing International Academy of Denver at Harrington elementary school — included any charter schools. And only seven Harrington students chose the charter schools in that zone.

Meanwhile, more than 200 other students from the 10 closing schools chose charter schools on their own. At least one Denver school board member has blamed the closures of district-run schools on charter schools siphoning away students, which is a common criticism.

But Huber pointed out that the percentage of closing school students who chose charter schools — 20% — is actually lower than the overall percentage of Denver Public Schools students who attend charter schools, which is nearly 24% this year.

And Huber said the trend of students leaving district-run schools for charters “cuts both ways.” About 88% of students from Girls Athletic Leadership School, a charter that will close its high school at the end of this year due to low enrollment, chose district-run schools next year, he said.

Olson, the school board president, said the result caught her off guard. She said she hopes to talk to families to learn why they chose charter schools like Rocky Mountain Prep.

“Is it because the school is close?” Olson wondered. “Is it because you have a cousin or relative who went there? Did they reach out? What can we learn from that?”

Olson has already been meeting with some families from the closing schools to gather feedback and connect them with district officials who can troubleshoot individual problems. She said most parents feel the same way that Chen does: They’re happy that they got into their first-choice school, but sad that they had to make a choice at all.

Chen lives four blocks from Palmer Elementary, where his daughter is in kindergarten. The school’s 8 a.m. bell time works well for their busy family, Chen said, and his daughter has loved being part of the after-school chess club, Spanish club, and Feel Good Club, which takes the students on walks and teaches them yoga.

Next year, Chen’s daughter will be among the 40 Palmer students set to attend Carson Elementary, a little more than a mile away. Both schools are district-run and have green ratings. While Chen feels Carson will offer a similar enough experience for his daughter, and eventually her younger siblings, it’s still not the outcome he’d hoped for.

“I would rather have Palmer still open,” Chen said. “I feel like the only thing we’re gaining out of going to a new school is a longer commute.”

Melanie Asmar is the bureau chief for Chalkbeat Colorado. Contact Melanie at masmar@chalkbeat.org.