Joseph Thomas was alone in his dorm room.

Perhaps that’s why his mind was racing. Why he couldn’t stop thinking about the future. He kept going over all the steps he needed to take over the next four years at Davenport University in Grand Rapids, Michigan, to achieve his dreams: a successful football season, a professional sports career, a practical backup plan.

And suddenly, while standing next to his desk, he had to take a deep breath.

“I told myself, I got to take it one step at a time,” the Detroit native said. “I have four more years.”

Four years.

That’s the goal. But here’s the reality: The first year of college for any student is difficult. Nationwide, nearly 30% of the first-time students who enter college don’t continue past their first year. Only 60% percent graduate in six years, and the proportion is lower for black and low-income students like Thomas.

And for Thomas and his classmates in Detroit, where years of tumult have taken their toll on local schools, the path to a college degree can be even steeper: Nearly half of graduates from Detroit’s main district who make it to college must take remedial courses. For charter schools in the city, it ranges from 32% to 75%.

Detroit graduates must navigate patchy academic preparation, culture shock, and often their own shaken confidence if they are to stay enrolled and on track to earn a degree that is their best chance to jump into the middle class as adults.

This year, Chalkbeat reporters in Detroit and Newark are examining whether students from struggling schools are prepared for college — and whether colleges are prepared for them. Catch up on the Ready or Not series here.

Local officials recognize the challenge. Some of the city’s publicly funded, privately managed charter schools — which enroll a little more than 32,000 Detroit students — have specific college-transition initiatives of their own. And Nikolai Vitti, superintendent of the city’s main district, has made bolstering college readiness a top priority, in his first year installing college counselors in every high school.

“Students that we know are smart, we know they’re talented, but they’re just not given the right exposure and experience to ensure that talent is actualized when they go to college,” he told Chalkbeat. “That’s our responsibility. That defines why we have to get better as a system. It’s unconscionable that students would leave our system and not be ready.”

But future improvements won’t affect Thomas and his fellow graduates in the Class of 2019, who spent the summer preparing for their first semester of college. They’ve started the uncertain journey already.

Marqell McClendon, the valedictorian of Thomas’ class at Cody High School, got into two of Michigan’s top public universities and while she’s pretty confident she’ll do well in most of her classes, math is another story. At Michigan State University, the school she chose, she’s taking a remedial class in math, her toughest subject, because she scored poorly on a placement exam.

It’s unconscionable that students would leave our system and not be ready.

Kashia Perkins and Demetrius Robinson, graduates of Jalen Rose Leadership Academy, spent part of the summer in programs meant to ease their transition to college. Perkins is also at Michigan State, where she’s giving herself pep talks as she wrestles with the fear of falling behind, while Robinson started at Central Michigan University, where he’s certain he can avoid a feeling that undermines so many students like him: that he doesn’t really belong on campus.

The four students all received enough scholarship and grant money to cover their college costs. But as the lead-up to the first day of class made clear, there’s much more to college than paying the bills.

‘Do you want this degree or not?’

More than a month before the beginning of the academic year at Michigan State, Kashia Perkins was already sitting in a college class, trying to keep up with a teaching style that was more fast-paced than what she was used to in high school.

“She was just fast,” Perkins said of the math instructor. “I would just have to make sure I was keeping up with the pace … and make sure I slow her down and ask a question if I need to.”

She spent the month of July taking math and biology classes while living in a dorm, part of a “bridge program” designed to get incoming freshmen studying in the college of engineering acclimated to the rigors of college classes.

Bridge programs have become increasingly common as colleges seek to recruit more students from underserved communities such as Detroit. Michigan State, for instance, has a number of them. The goals vary from program to program, but in general they seek to ease the transition to college and provide guidance and resources for freshmen if they run into trouble.

She also joined Detroit M.A.D.E. (Mastering Academics Demonstrating Excellence), a program that provides support to incoming freshmen from the city of Detroit specifically.

That she’s even at one of the state’s most selective universities at all is a dramatic shift considering Perkins’ first two years of high school.

She wasn’t serious about school, wasn’t paying attention in class, and she preferred hanging out with her friends. Her grades were suffering.

Then came a visit from her grandmother. Perkins thought she was there for a friendly chat. She wasn’t.

I just need to go in with the mindset that I can do it. And I will.

Her grandmother, in fact, was there to make a point. And she made it painfully clear Perkins needed to change her ways, telling her to “stop messing up,” and “get your act together.”

The message was effective. It set Perkins on a different path. She now calls it a turning point. But really, it was a return to normal. Her mother, Kymberly Burton, said Perkins was a go-getter from the beginning, and always on the honor roll until those early high school years.

She said she tried to instill in her daughter the importance of doing well in school, “because I didn’t want her to become a statistic,” Burton said. “I never doubted her.”

A key part of the turnaround for Perkins was when she enrolled at the Jalen Rose academy, where there’s a robust college-going culture. The high school has a team of adults whose sole job is to prepare students to enter and be successful in college, including an alumni success adviser who has a role that doesn’t exist in most schools: She works with students after they’ve graduated and enrolled in college, visiting them and helping with everything from financial aid to academic concerns.

School officials have invested in this college success effort because they were concerned that too many graduates were going on to college, but not lasting.

David Williams heads up this team and often reflects on his own background as someone who dropped out of high school in the 10th grade in Detroit. After later earning a general education equivalency diploma, he enrolled in college — because, he said, he wanted to be able to provide for his son — and now has a doctorate in educational leadership.

“I think one of the reasons I dropped out is … we didn’t see a lot of college successes,” Williams said. “We didn’t see a lot of people graduating from college. And the people who did, they would leave.”

Perkins finally got serious at Jalen Rose, and in June she graduated with a 4.1 grade point average during her time at the school. At Michigan State, she’s planning to major in human biology. She wants to become a pediatrician. It’s not surprising, given she said the toughest part of being away from home is being away from her sister, who is a toddler.

It’s also not that far from her childhood dream of becoming a lawyer, which she said was fueled by her dislike for how children in foster homes are treated and her belief that she could “be the person who stands up for them.”

Even as a pediatrician, she said, she can look out for children.

“I just always want to make sure kids feel good, they feel comfortable, safe, and stuff like that,” Perkins said. “It just always bothers me when kids are pushed aside or mistreated.”

And she doesn’t plan to fall into the trap that befell her during her first two years of high school.

“I’m at school to handle my business,” Perkins said. “I’ve matured since then. I just need to go in with the mindset that I can do it. And I will.”

A key strategy: Be careful about who she hangs out with. She’s heading to MSU with a group of friends with a similar mindset who she said will push her and check her if she gets off track.

Despite her confidence, Perkins said her biggest fear “is falling behind and not being able to catch up.” Overcoming that fear can be as simple as a solo pep talk.

“I just tell myself, ‘Do you want this degree or not?’”

‘I was trying really hard not to cry’

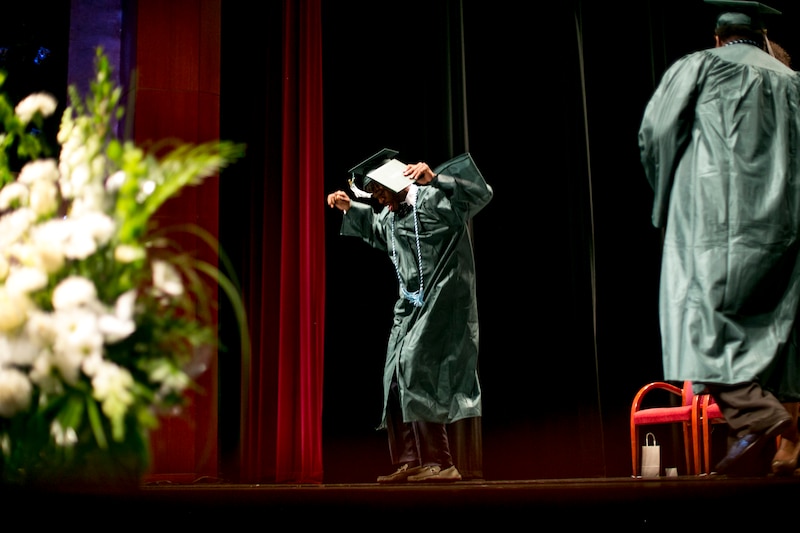

The crowd roared with applause as Marqell McClendon stepped toward the podium, ready to deliver her valedictorian’s address during Cody High’s graduation in June.

Just a few minutes before, during an introduction that was both emotional and hilarious, one of her favorite teachers had roasted her, outing her mastery of forging her mother’s signature on a field trip form. But the teacher, Jennifer Weaver, also provided a touching tribute, choking up as she contemplated losing her “right-hand” person.

“Marqell is the type of student that every teacher wants,” Weaver said. “She’s the one you trust to help you with things. She’s the one you want to represent your class in front of administration.”

Then, it was McClendon’s turn. A top student and dedicated debater who had been admitted to the state’s most selective public universities, she had prepared a speech in which she remarked on the transition that had marked her senior year, when three schools on the Cody campus merged into one. She also urged her fellow graduates to persevere beyond obstacles, telling them, “obstacles and difficulty are nothing to be ashamed of,” and urging them to remember three things if they ever feel stuck: Distance yourself from drama, don’t allow pride to get in the way of asking for help, and never quit. But even as she stuck to her prepared speech, Weaver’s words simultaneously had her wanting to fight back tears and feeling proud of her accomplishments.

It also had her thinking about the weight of that day, and how graduation “being the beginning of a new journey for me was emotional because I honestly don’t know what’s in store for me next.”

And she wasn’t ready to bask in the euphoria of graduation because, she said, “I know I’ll be right back at school in two months.”

That was in June. In late August, McClendon moved into her dorm, ready to begin studying biomedical science at Michigan State. Her goal: She wants to help impoverished countries solve medical crises.

“We in the U.S., we have way more resources than we actually use and there are more people, or more countries out there that could use that too. One of the first things I would do is travel and try to figure out those problems and then come back and find ways we can fix them.”

For now, McClendon’s most immediate challenge is her fall course load, which includes remedial math. It was something she predicted would happen in May during an interview with Chalkbeat, when she said she hadn’t felt challenged in high school and even went without a permanent English teacher for several years.

“I don’t have a problem with it,” she said. “I know it’s something I have to do, and I’d rather take those classes in order to help me than starting way above my ability.”

On her first day at MSU, she was unpacking all of her items from home, with help from her mother, sister and aunt, when a familiar face stopped by her room.

It was Antoine Douglas, who the last two years was the college adviser at Cody High in Detroit — placed there through a Michigan State program. It was a job that required him to help Cody students navigate the college preparation and application process, and McClendon was among those who benefitted.

But now Douglas, who is working on his master’s degree in business, is on campus full-time and is a residence hall director.

A lot of people in today’s society, a lot of teenagers, aren’t making it this far.

So when he stopped by her room on that first day, it was a reminder to McClendon that she has someone in her corner who lives close by and has many campus connections. It was Douglas, after all, who helped get her into the Charles Drew Science Scholars program at Michigan State, which provides support to students enrolled in majors through the College of Natural Sciences.

“He does like to check on us and make sure that we’re doing good,” McClendon said. “It was nice to see him and if I do need any help throughout the week or throughout the year even, I know he’ll be close.”

That kind of connection is important for first-year students, who can struggle with being on their own for the first time and not having their parents or teachers to lean on. For urban students from Detroit, it can be a culture shock.

The district is working to make that an easier transition. Vitti two years ago allocated enough money to ensure that every high school in the district has at least one person dedicated to helping prepare students for success. The district has expanded dual enrollment options for students that allow them to take high school and college classes simultaneously. And, he said, the district is putting more resources and time into improving performance on the SAT, which is important because a good score can qualify students for scholarship money through a program called the Detroit Promise.

That scholarship program is among the ways McClendon is paying for college. When she moved into her dorm Aug. 24, she dealt with a range of emotions — from the tears that began the day as she said goodbye to her close cousins to later, when her emotions were in check as she arrived at Rather Hall on the Michigan State campus — her mother, aunt, and sister in tow. She registered, got her key, loaded up three big bins with her stuff, then opened the door to her room.

“It’s bigger than I thought,” she said with relief.

‘I’m going to do everything full force’

At 17, Demetrius Robinson already sounds like a savvy salesman for the family fitness business he dreams of taking over when he graduates from Central Michigan University.

This business, he told his peers during a presentation at Jalen Rose in May, will be bigger than any of the centers that are popular now.

Why? “You’ll have to come to us. We’re going to meet all your needs. We’re going to make sure you’re taken care of.”

And then, drawing laughs from his classmates, he added, “We’re going to make sure you get that summer body.”

Brimming with confidence, Robinson has devised a plan with his brother. Cameren Robinson, who works in advertising and marketing in New York, will handle the business side. Robinson, who plans to major in athletic training, will lead the physical side of the company. And their parents, LaSandra and Demetrius Robinson, Sr.? “All they have to do is sit back and watch the business boom,” Robinson said.

In a state where nearly 40% of black male students don’t even graduate from high school on time, McClendon said he’s determined to be different, saying, “I’m going to do everything full force, how I planned it and the way it’s supposed to be done.”

“A lot of people in today’s society, a lot of teenagers, aren’t making it this far. So, it’s really an accomplishment for me. I’m really keeping my neighborhood, everyone around me, proud because they’re seeing I haven’t fallen into that trap that society has put young black males and females into. I’m proud of myself.”

Already, Robinson is making a name for himself on campus. When he visited for orientation in August, he showed an ease on campus, flashing his big smile, shaking hands and meeting new people. And he’s quickly established himself as a person to go to for haircuts and help with fitness training. It’s part of his plan to be as involved in college as he was in high school, where he played several sports and was in other organizations.

Like McClendon and Perkins, he’s also getting special help from his college, as part of a program meant to ease the transition for first generation college students and those from low-income families. He said learning has always come easy, but he plans to seek out tutors and late night study sessions if he begins to struggle. And, he said, he has to keep one thing in check: His habit of procrastinating. Too often, he said, he’ll wait until the last minute to meet deadlines. He said he’s always been able to turn in quality assignments. But that was high school. The stakes are now much higher.

As much as Robinson credits his parents for inspiring him, it’s clear that he and his brother have also inspired their parents, both of whom graduated high school and did brief stints in community college. His father, for instance, is back in school himself at Henry Ford College, working toward a physical therapy assistant degree. He eventually wants to become a doctor.

It started when his oldest graduated from college.

“Seeing him walk across the stage, I’m like, ‘Oh, I got to do something to keep inspiring them to keep moving forward.’”

You can do the work. You just need the opportunity.

One of the things Jalen Rose students learn about during the college preparation process is what they describe as the “imposter phenomenon” — that feeling of not belonging that students from urban areas like Detroit often feel when they go to college.

It’s a reality for many first-year students who arrive on campus and feel others who were exposed to far more opportunities are “better” than them, said Williams, the dean of college at Jalen Rose.

“Our job is to let students know that it’s an opportunity gap, it’s not an achievement gap,” Williams said. “You’re not less than. You can do the work. You just need the opportunity. But once you get to school, you might not be on the same level as the student sitting next to you, so it’s now your responsibility to work that much harder.”

‘I have to do it on my own’

Joseph Thomas has been feeling the pressure. He’s the first in his immediate family to go to college, an opportunity he says he wouldn’t have without football. He feels an enormous responsibility to be a role model to his younger siblings.

That pressure can be overwhelming. “But it’s what keeps me going,” Thomas, 18, said.

He has family members who’ve spent time in prison, and he wants to show those younger than him that there’s a better way. It’s an important thing for Thomas, who’s tried hard and sacrificed so much to stay out of trouble. There were the parties he didn’t go to. Or the ones he simply made an appearance at. There were the times he turned down hanging out with a big group.

Seeing his family members imprisoned, he said, “made me think about how my little brothers and sisters would feel if they see me locked up. I just didn’t want to put that on them.”

He also wants his younger relatives to know that it’s possible to overcome obstacles.

Thomas was an honor roll athlete, always placing his school work on the same level of importance as playing football. When he participated in a college decision day event at Cody in May, in fact, he wore a black shirt with the words “More Than An Athlete,” written in green letters. At Cody, he participated in dual enrollment classes, taking courses taught by college instructors.

”I always went to class,” he said. “I never talked back to the teacher. I just knew what I was supposed to do.”

But not everything was easy for Thomas. When he was around 11, he says, he and his siblings bounced from home to home because of problems in their own home. He learned then how to be independent. He also learned, at an early age, that if he wanted something he had to get it for himself.

That’s how he came to play organized football. He wanted to play on a community team, but knew his parents couldn’t afford the equipment. So this savvy teen made the coach, who had a painting business on the side, an offer:

I’ll help you paint houses, he told him, to cover the cost of the equipment.

His ultimate goal is to play professional football. But he’s already preparing for what he calls his “fallback plan.” At Davenport — a growing university with multiple campuses across the state and a new initiative helping prepare students to teach in urban systems like the Detroit school district — he’s planning to major in industrial production management, which would prepare him for jobs overseeing operations at manufacturing companies.

He said he knows he will have to make academics a priority while playing football. “I can’t play football if I don’t do this work. I see myself as a student-athlete, not just an athlete. I already know school comes first,” he said.

So here he was now, more than four years after picking up that paintbrush, moving into his dorm room and preparing to start classes and his first college football season. He did it alone.

“Growing up, I’ve never really had that close support system that was with me every step of the way,” Joseph said. “But at the end of the day, I realize it’s your life and you have to make the best of the moments God blesses you to have and I just walk through every door that opens for me with my head high.”

This story is part of a partnership with Detroit Public Television. Watch a special segment about it during the “One Detroit” program at 7:30 p.m. Thursday. It was produced with support from the Education Writers Association Reporting Fellowship program.