Nearly 30 years ago, Michigan lawmakers passed legislation creating a new category of schools called public school academies, or charter schools, as an alternative to traditional public school systems. Advocates said these schools would operate with more autonomy and usher in an era of expanded school choice, educational innovation, and higher academic achievement.

From the very start, there was confusion about what these schools were, including conflicting court rulings on the fundamental question of whether they were public or private.

Even today, with 150,000 K-12 students enrolled in Michigan charter schools, a good deal of misunderstanding — and conflict — persists over what charter schools are, how they differ from other types of schools and how well they deliver on their promise.

Ron Rizzo, director of charter schools at Ferris State University, said that the basic definition was “one of the biggest questions” when he started working in the sector 21 years ago. “And it hasn’t gone away.”

Indeed, the complexity of Michigan’s charter school law resists simple definitions. And political divisions over education policy continue to cloud the debate over their merits: Republicans generally favor charter schools, while Democrats have been skeptical of them, leaving the public to sort through competing and frequently misleading characterizations.

Today’s charter school sector was largely shaped by Republicans, who controlled the Michigan Legislature for nearly four decades. Working with allies in the school choice movement, they have eliminated caps on the number of charter schools and sought to minimize interference from local officials in how they operate.

Now Democrats control the Legislature, and with the backing of teachers unions and public school advocates, they are pledging to rewrite laws governing charter schools.

For families and educators seeking to navigate the latest turn in the debate, it’s important to understand what charter schools are, how they work, and what proposed changes in the law could mean. Here’s a guide to help you:

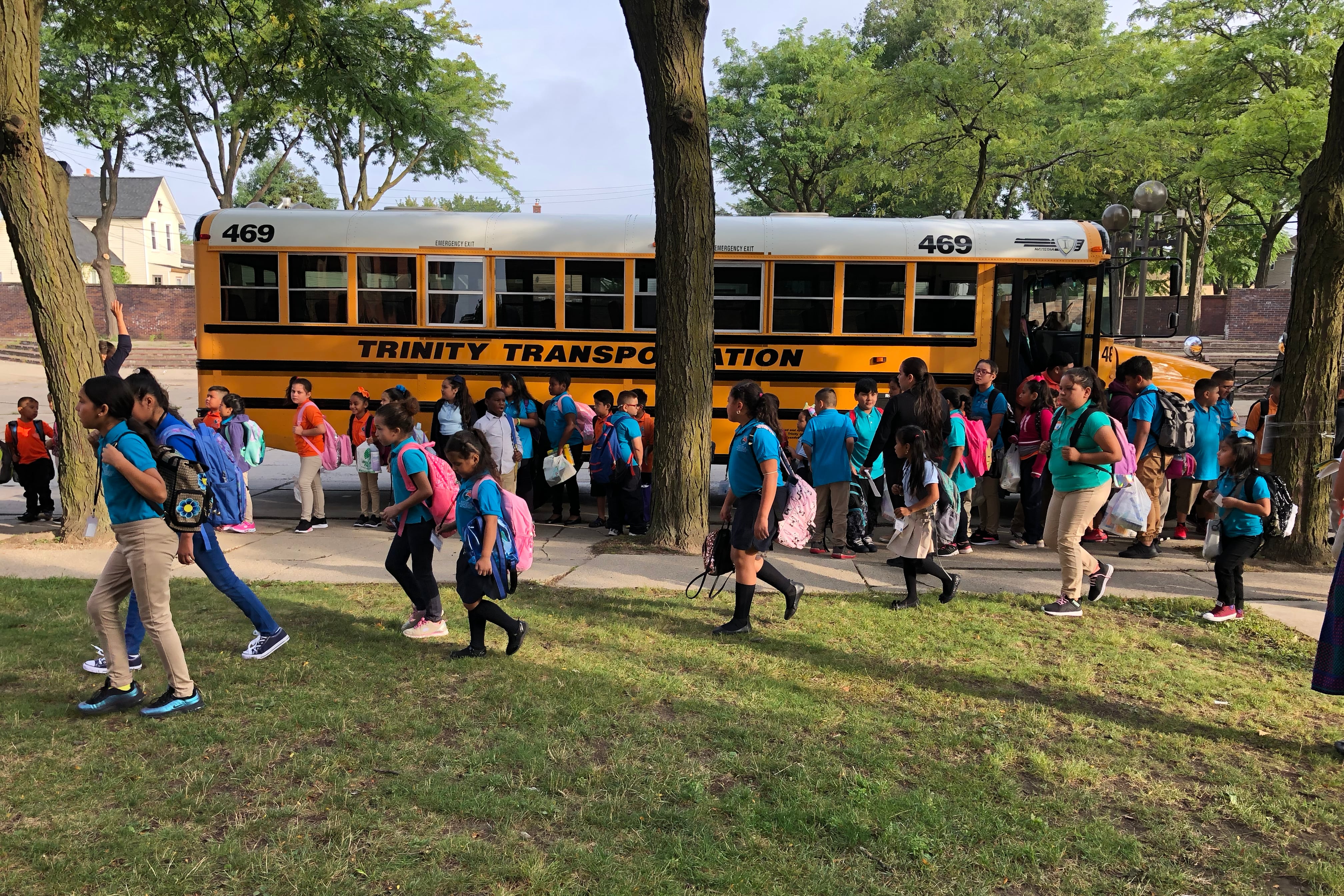

Charter schools serve a large segment of Michigan students, mostly in cities

There are about 370 charter schools in Michigan enrolling roughly 150,000 K-12 students, or 10% of the total. Some of those schools are organized into groups called charter districts.

Most charter school students live in urban areas, notably Detroit, where nearly 50% of all public school students attend charter schools. Nearly two-thirds of charter school students are enrolled in southeast Michigan.

After a period of rapid growth, particularly in the early 2010s, the number of charter schools has plateaued, along with their enrollment.

They are public schools

Michigan’s charter school law was nearly short-circuited by a legal challenge arguing that charter schools were private, and not eligible under the state Constitution to receive public money.

At first, the courts agreed, but the state Supreme Court ultimately said explicitly that charters were public schools. That means they qualify to receive taxpayer funds. Today, charter schools are almost entirely supported by state tax revenues.

As public schools, charters must follow state and federal education laws governing standardized tests, teacher certification, discrimination, the rights of students with disabilities, and the rights of students learning English as a second language, among others.

Charters are managed differently than other public schools

Michigan law allows anyone to open and operate a charter school, but they can’t do so on their own. The term “charter” refers to the contract that a school operator must sign with an outside body called an authorizer — usually a college or university, but sometimes a local school district.

The authorizer functions as that school’s regulator, responsible for ensuring that it complies with state standards and education laws and meets benchmarks for academic performance. Authorizers typically review a school’s charter for renewal every five years. In exchange for oversight, authorizers can take up to a 3% cut of a charter’s state funding.

The authorizer also appoints members of a board that more directly oversees the charter school, or a group of schools in a charter district, just as an elected school board would for a traditional public school district. Even though they’re not elected, the charter school boards are considered public entities, and their deliberations are subject to open-records laws.

But many charter schools hire outside companies to handle key aspects of their operations, from hiring teachers to balancing their books. In Michigan, unlike in many states, most of those companies are for-profit. The largest among them manage dozens of schools.

The management companies are not public entities, which means the public isn’t entitled to access data about how they spend money on behalf of the schools, or how much profit they earn.

They often work on a tight budget

Charters take in less funding on the whole.

During the 2020-21 school year, charters reported about $12,100 in total revenue per pupil, compared with $13,400 per pupil for local districts.

Like the vast majority of local districts, charters receive $9,150 per pupil in state aid, plus some federal aid.

But they don’t receive local tax revenue, which districts often tap for building improvements.

Charters also tend to run at a lower cost. On average, they pay teachers less and spend less on instruction than local districts. Few charter schools have staff represented by teachers unions, and they generally don’t contribute to the state’s educator pension fund. While a handful of charter schools provide busing, they typically have almost no transportation costs. They enroll a lower proportion of students with disabilities, who are most expensive to educate.

A handful of charter schools receive substantial private donations that allow them to maintain newer buildings and spend more in the classroom.

They are a political battleground

For most of its existence, the U.S. charter school movement has had the support of both political parties.

Even so, in Michigan and elsewhere, charter school debates are often fiercely partisan.

Republicans, during decades of political control in Lansing, built a charter system designed to promote competition among schools, with few restrictions on who can open a school and where schools can form.

Democrats, with the backing of teachers unions, argued that limited regulation of charter schools created a chaotic landscape in Michigan cities where too many schools compete for a shrinking pool of students. Critics also worry that charters allow private management companies to profit from public education.

The cities where charters are most common are Democratic strongholds, but debates in these communities don’t always fall within party lines. Many families in these areas embrace charters as an alternative to struggling school systems. Others worry that charter schools will make things worse for their local district by pulling students — and funding — away.

They haven’t produced much change or improvement

Education reformers who built Michigan’s charter law saw the schools as a potentially transformative force.

“With charter schools, you get away from the one-size-fits-all mentality that has imposed a deadening uniformity and all too often a mediocrity on so many of our public schools,” then-Gov. John Engler, a Republican, said when the law was proposed.

Charters were said to be especially beneficial for students in low-income communities with struggling school districts, who would be allowed to opt out of their local school to attend an innovative, high-quality alternative.

In practice, charters have produced little educational change. With a handful of exceptions, their classroom operations generally mirror their district counterparts, as do their academic results.

In Detroit, for example, charters do slightly better on standardized tests than district schools, on average, but still fall well below state average scores.

Koby Levin is a reporter for Chalkbeat Detroit covering K-12 schools and early childhood education. Contact Koby at klevin@chalkbeat.org.