Sign up for Chalkbeat Indiana’s free daily newsletter to keep up with Indianapolis Public Schools, Marion County’s township districts, and statewide education news.

As the clock ticked down to the start of the school day at 8:05 a.m, Courtney Smith kept an eye out for the couple of students who were often absent.

Every morning last school year, Smith — the assistant principal at Pleasant Run Elementary in Warren Township schools — would call their parents, sometimes waking them up, to tell them that school was about to start. Eventually, Smith said, they began to expect her call. And in the end, their children’s attendance improved.

“They knew we cared,” she said. “They will show up, maybe late, but they’re still here.”

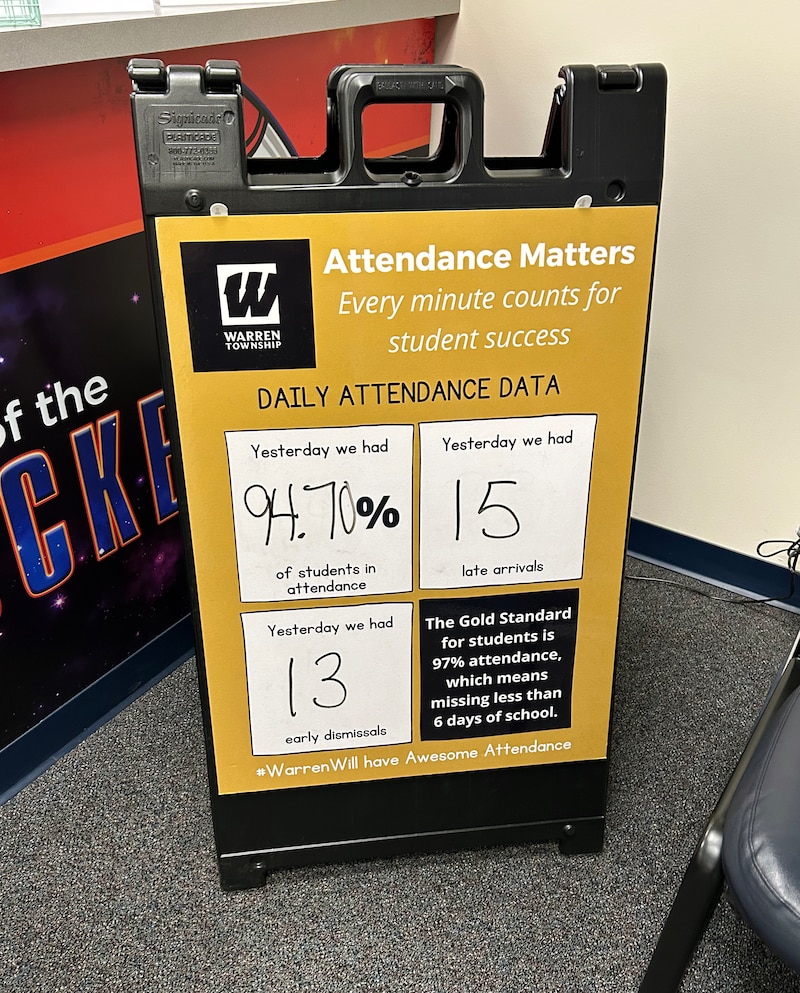

Pleasant Run is part of an all-hands effort that began last school year at the Metropolitan School District of Warren Township to improve student attendance and curb chronic absenteeism, which has spiked across Indiana and the nation in the wake of the pandemic.

Indiana policymakers have indicated that during the upcoming legislative session they may seek to reinforce existing laws on absenteeism, which can include punitive measures for excessive absences. These allow local prosecutor’s offices to take parents and teens to court, and make students ineligible for drivers’ licenses.

“We just want to make sure it’s a focus again, because anything good we do in the education system, for those kids who aren’t there, they’re not going to have success,” said Senate President Pro Tempore Rodric Bray, a Republican.

Yet education officials and experts say family engagement at the school level is more effective at curbing absenteeism. Punitive approaches, they argue, don’t solve the core issues that lead students to miss school.

Data for Marion County from statewide and local agencies show that officials rarely used enforcement measures prior to the pandemic, and in some cases they’ve become even less common since then as officials aim for an approach that doesn’t send families to the justice system.

Nationwide, schools have cited a long list of reasons that absenteeism hasn’t fallen to pre-pandemic levels. These include confusion over when to keep sick kids home; ongoing mental health concerns and students’ own unwillingness to attend class; and greater socioeconomic needs in some areas. Transportation, childcare, and work schedules have also presented obstacles for some families, advocates say.

Warren Township schools can point to proof that its approach is working. Out of all the Marion County school districts, it’s had the biggest drop in what the Indiana Department of Education calculates as chronic absenteeism, from 63.5% of students missing 18 or more days of school due to excused or unexcused absences in 2020-21, to roughly 26% last school year. Pleasant Run Elementary’s rate declined from 37.2% to 15.1%, according to state records.

What’s made the most difference is a focus on communicating with parents about attendance, school officials said, an effort spearheaded by the district’s new parent liaisons and supported by a new attendance system — all of which require resources, they added.

“We’re not there to attack them with attendance, we’re there to help and support,” Smith said.

Attendance enforcement drops in Marion County

State law provides several enforcement measures for students who are “habitually” absent, or parents of younger children who routinely fail to bring them to school. A “habitual truant” is defined in the law as a student who accrues more than 10 days of unexcused absences in the school year.

School officials must report a child who is habitually absent to the Department of Child Services, which handles cases of educational neglect on behalf of a parent, or juvenile court, which addresses the failure of older students to bring themselves to school.

State law also requires school officials to file affidavits in local courts against parents, who may then be prosecuted.

But even prior to the pandemic, the Marion County prosecutor’s office rarely filed cases against parents, and the current administration has revamped a diversion program to address root causes of absenteeism and keep families out of the court system. Only 29 criminal cases were filed from January 2014 to October 2016, for example, according to data from the office. Two resulted in misdemeanor convictions — resulting in a few days in jail, and in one case a bond of $145. The rest were dismissed.

Schools often refer students who miss around 20 to 30 days of school to the diversion program, said Jake Brosius, the youth programming coordinator with the prosecutor’s office. Brosius — a social worker by trade — calls families to understand why they’re missing school.

Sending families to court does not address the root cause of absenteeism, Brosius said.

“If they attend a court hearing, they can’t go to work that day,” he said. “And a lot of the families we work with are in those kinds of positions where each and every day can be a struggle.”

There were 11 referrals to the diversion program in the 2020-21 school year, then 30 in 2021-22, and 19 last school year. As of Oct. 31 this year, there has been one.

Data across other agencies also show a decline in punitive measures for absenteeism, which some officials say is a result of schools adopting alternative responses.

The Marion Superior Court Probation Department, which receives referrals from schools dealing with older truant students, received 47 referrals in 2021 and 20 in 2022. As of early December of this year, the department had received none. After an investigation into the alleged absences, those referrals are forwarded to the prosecutor’s office for a decision on whether to prosecute.

Marion County Chief Probation Officer Christine Kerl said many school districts are responding in ways that indicate their belief that “the court may not be the best response.”

“I think that does play into why we see so fewer truancy referrals than we did 10 years ago,” she said.

State law even allows school districts to list habitual truants age 15-17 as ineligible for a driver’s license with the Bureau of Motor Vehicles. Figures from the BMV show that since 2019, that figure peaked in 2020 at 32 students, then fell to 28 in 2021 and seven in 2022, before rising to 14 as of Oct. 31 of this year.

Still, Marion County absenteeism rates remain higher than the statewide average.

Lawmakers and state board of education members have recently raised alarms about these statistics, linking high rates of absenteeism to declining test scores. They’ve also called for more action focused on parents, whether through enforcement or awareness.

“I don’t know what can be done, but there has to be, in my opinion, a way to hold parents of minors accountable for those students not coming to school,” said State Board of Education member William Durham at an October meeting.

Legislative leaders have already confirmed that they’ll pursue a bill related to absenteeism in the upcoming legislative session, which begins in January.

Bray, the Senate president pro tempore, said at a November legislative preview event that lawmakers would look to existing enforcement measures provided by the Department of Child Services and other agencies, rather than create a new system to address absenteeism.

House Speaker Todd Huston added that existing laws needed to be reinforced.

Lawmakers could update state code to give a clearer picture of the reasons that students are absent, said Carolyn Gentle-Genitty, a professor at Indiana University who worked with Warren on improving attendance. She said doing so would shine a light on instances of “school withdrawal,” for example, where students are missing school because of instances like waiting for a repairman because their parents are at work.

Schools could then target their support, she said: A child who has ‘school refusal’ isn’t going to school due to challenges like bullying and anxiety, and needs a different type of intervention than a child experiencing school withdrawal.

How a trophy and stickers can improve student attendance

But there’s a gap between what some officials want and what research says may work best in reducing absenteeism.

Illinois schools that had strong family engagement prior to the pandemic had a chronic absenteeism rate that was 39% less than similar schools with weak engagement, according to a study released in October from the Learning Heroes nonprofit and The New Teacher Project.

Families understand the importance of education and want to send their children to school, said Kate Roelecke, director of strategy and operations at the Marion County Commission on Youth. But they may face obstacles like their work schedules, or a lack of transportation and child care that force older children to be responsible for younger siblings, for example.

Roelecke said the commission hopes to work with lawmakers on solutions that connect families to community resources. She said she’d rather see lawmakers study the issue of absenteeism this summer than address it in a rush during this session.

“We all want the same thing, we want kids to be getting a great education and we know being in school is a key piece of that,” she said. “I don’t think we’re going to accomplish that by putting parents, students, and schools on the defensive.”

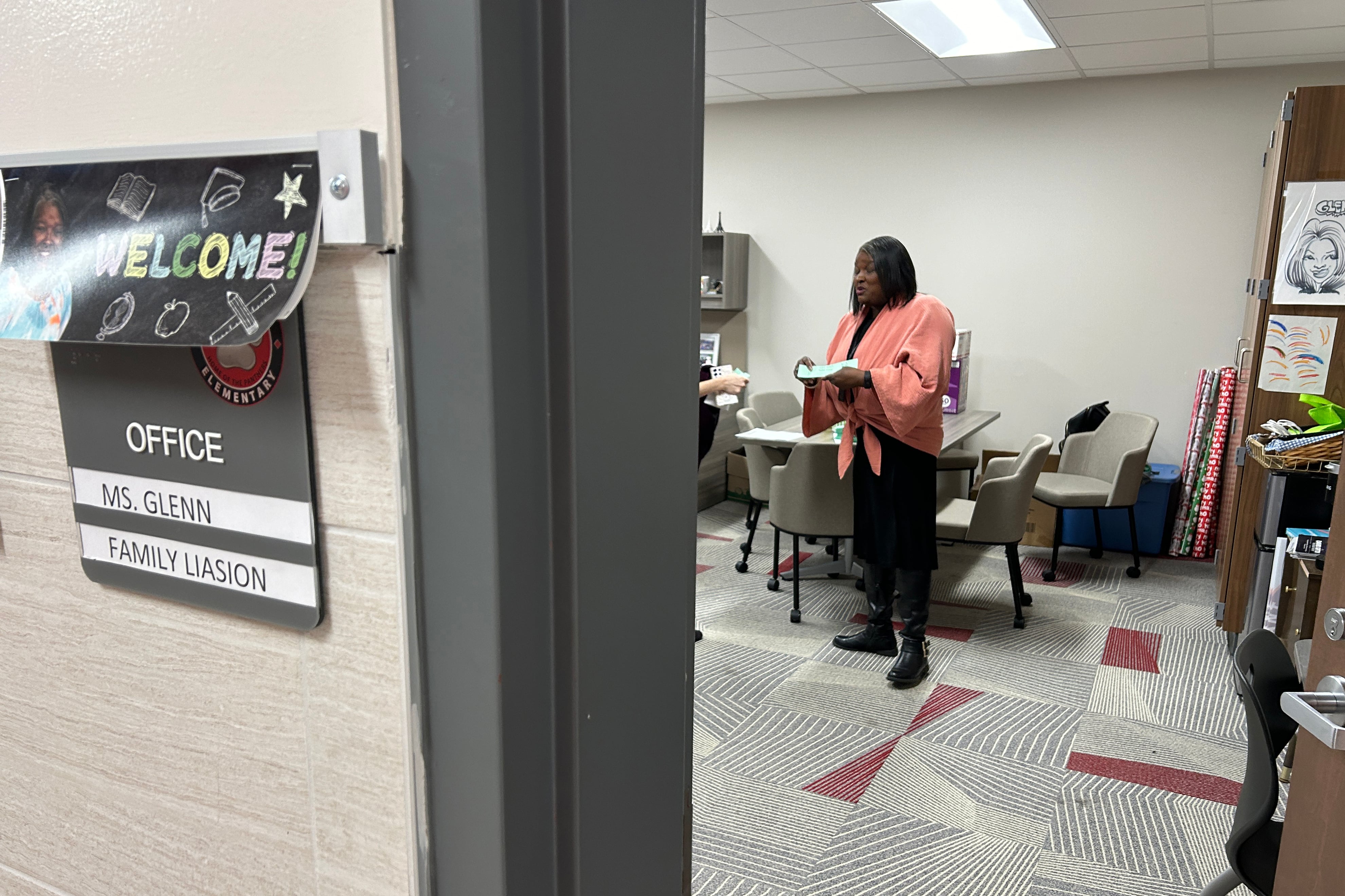

At Pleasant Run Elementary, a five-foot trophy towers in Yvette Glenn’s office, waiting to be awarded to the classroom with the best attendance of the week. Glenn is the school’s family engagement liaison — a position funded by tax increases recently approved by voters — and is constantly coming up with creative ways to entice students to school.

“Our kids really want to be here too. They’re not asking their parents to stay home,” said Smith, the assistant principal.

Warren schools also adopted last year a new district-wide attendance system called RaaWee K12 that automates many aspects of tracking absenteeism. It flags which students need a call home, a letter home, or even a parent meeting after a certain number of days missed.

In the past, letters sent home about attendance were impersonal and made little improvement, Smith said. What’s different now is that calls and letters home come from teachers and staff seeking to understand why a student has been absent, and offering help with finding a solution.

“We’re learning a lot more about our families in a positive way,” Smith said. “Not due to the fact that they’re absent 15 days and we’re saying, ‘hey, where are you?’ We’re hitting that early on, and they’re able to share what their needs are.”

Aleksandra Appleton covers Indiana education policy and writes about K-12 schools across the state. Contact her at aappleton@chalkbeat.org.

Amelia Pak-Harvey covers Indianapolis and Lawrence Township schools for Chalkbeat Indiana. Contact Amelia at apak-harvey@chalkbeat.org.