The assignment started out easy. Two students acted out a conversation between a teacher and a student about homework help.

Then it got trickier.

The students needed to apply the same principles of communicating and listening effectively to a conversation between two romantic partners about having sex for the first time. And they had to use all the knowledge about healthy relationships, preventing pregnancy, and sexually transmitted diseases that their weeklong sex education class had just covered.

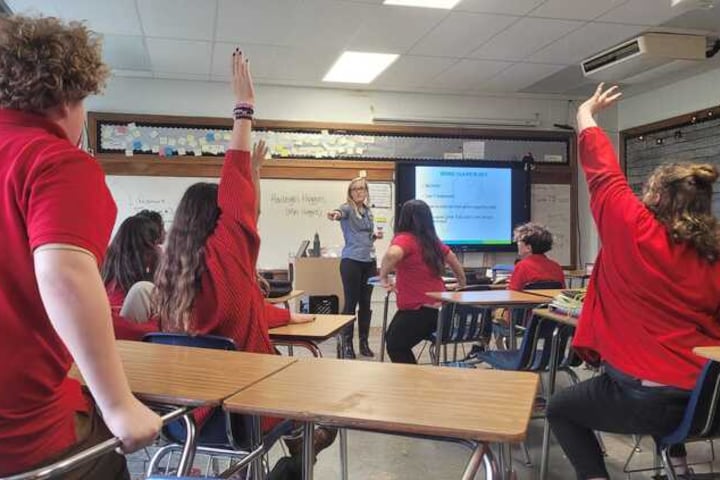

There were no wallflowers or shrinking violets in Haileigh Huggins’ class at Irvington Community Middle School, as nearly every hand shot up for a chance to perform the skit. But there was some giggling.

“This can feel a little awkward. A little weird,” Huggins told the students after they quieted down. “But the more we practice difficult conversations, the better we get. Remember: The only person who can make a decision about your body is you.”

Sex ed that covers birth control, pregnancy, and consent isn’t required in schools in Indiana.

Lawmakers and advocates have tried to change that, especially in light of the state’s abortion ban and statistics showing a decline in the number of students who receive sex ed at school or at home. But such efforts — including two bills on sex ed in the current legislative session — face an uphill battle as disputes about how schools should address complex social topics play out in Indiana and nationwide.

Despite evidence linking sex ed to improved behavioral outcomes, like delaying sex, Indiana is one of 21 states that does not require the course in schools.

It mandates only that schools teach lessons on HIV and AIDS, and expects schools that do teach sex ed to emphasize abstinence. Past bills to expand what schools need to cover have not been called for discussion, and other legislation this year instead seeks to place limits on classroom conversations about topics like sexual orientation.

Without statewide sex ed requirements, Indiana students might receive an incomplete education depending on where they go to school, experts say.

“When young people are given the information they need, they’re able to make really good decisions for themselves. They can ask questions, feel affirmed in who they are as individuals,” said Alison Macklin, director of policy and advocacy at SIECUS: Sex Ed for Social Change. “Their experience will be vastly different from kids who didn’t get that education.”

Access to sex education in Indiana varies

Huggins had worked with many of the students in the class before, which helped put the teens at ease.

As an educator with LifeSmart Youth, a nonprofit organization that contracts with schools to offer sex ed, she taught their fifth grade course on puberty and the basics of reproduction. The curriculum begins with elementary school lessons on bullying, then turns to talks on healthy relationships that emphasize abstinence per Indiana law, but include all methods of contraception.

Now in seventh grade, the students had spent the week talking about different birth control methods and their effectiveness at preventing pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases.

Their last day for the class was spent learning to communicate, first through familiar scenarios like asking for homework help and listening to the response. Then they applied the same principles of expressing their opinion and respecting their partner’s reaction to a mock conversation about safe sex.

One student read prompts — “What does safer sex mean to you? What else do we need to talk about?” — while another ad-libbed responses — “I think condoms would be a safer choice.”

The students performing the skit didn’t falter, and their classmates remained quiet and attentive. If the assignment was a little awkward, it was also an incredibly important example, Huggins said.

“You’re allowing us to hear these conversations,” Huggins told them.

But data indicates that fewer of these kinds of conversations are happening around the state.

Around 65% of students in 2015 said that their parents talked to them about sex, compared to 55% in 2021, according to the Indiana Department of Health’s 2021 Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Additionally, the share of middle schools that taught students about the efficacy of condoms has dropped in that time period from 58% to 41%.

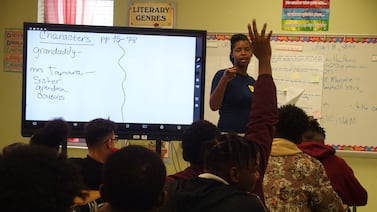

LifeSmart CEO Tammie Carter said the organization has a waiting list of schools interested in the program. However, she noted that it has also seen districts drop the program in the wake of legislation that would restrict classroom conversations about “divisive concepts.”

This year, lawmakers are again considering a bill that would prohibit teachers from raising certain topics on race and discrimination, as well as another that would ban discussions of sexual orientation and gender identity from K-12 schools.

It’s not clear how many schools in the state include a sex ed curriculum.

But students in schools that do offer sex ed are likely to have better behavior outcomes in the near- and long-term, said Macklin of SIECUS: Sex Ed for Social Change, including choosing to delay sexual activity or use contraception.

An ideal sex ed curriculum would be aligned to recommendations from pediatricians, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and experts in child development, Macklin said. It would be structured as a K-12 framework, beginning in the early grades with topics like not touching others without permission.

It would also change the state’s requirement for schools to emphasize abstinence — one of the few requirements for schools that offer sex ed.

Bills to teach sex ed face challenges

Two bills in the Indiana House seek to expand what the state requires of a sex ed course, though neither would make the lessons mandatory in schools. Since 2018, Indiana has required schools to give parents a chance to opt students out of the lessons, which would not change under the bills.

House Bill 1066, authored by Rep. Sue Errington — a Democrat who at one time worked for Planned Parenthood and has brought the similar legislation forward in past years — and House Bill 1566, authored by Republican Elizabeth Rowray, would each require schools that do offer sex ed to provide medically accurate, age-appropriate sexual health education. That education would have to be applicable to all students regardless of gender, sexual orientation, and whether they’re sexually active.

The bills specify that schools that opt to provide sex ed must offer it to students once in fifth grade, twice in middle school, and twice in high school. And they emphasize teaching abstinence as the most effective way to prevent pregnancy and disease, but not to the exclusion of other methods of contraception.

Rowray, who supported the state’s ban on most abortions that passed last summer, said she sees education as key to reducing the number of unwanted pregnancies in Indiana.

“It’s important for everyone regardless of identities to understand the ramifications of having sex and how it can impact you from a physical, mental, and emotional standpoint,” Rowray said. “Having the facts will dispel the myths.”

Rowray previously served as the director of a crisis pregnancy center — an organization that dissuades clients from having abortions — that offered sex ed to local schools. In this role, Rowray said she heard students repeat a number of inaccuracies about sex and pregnancy — like that they couldn’t get pregnant in a hot tub, or if it was their first time.

But one comment from a student stuck with her, Rowray said: A teenage girl wrote that until taking a sex ed class, she didn’t know she could say no to having sex with her boyfriend.

Around 17% of female students reported being forced to have sex they didn’t want to in 2021, compared to 15% in 2015, according to the state’s youth behavior survey.

“You might give consent one, 10 or 50 times, but you can choose to revoke that consent and say, this is not a healthy choice for me at this time,” Rowray said.

Rowray said she’s not sure if her bill has support from her statehouse colleagues. Neither bill has thus far had a hearing in the House Education Committee, like similar bills in the recent past.

She added that she hopes Indiana makes sex ed in all schools mandatory.

Educator training crucial for sex ed

In addition to curriculum, Macklin said it’s important for sex ed legislation to consider how to train educators in the topic.

It’s not uncommon for schools to turn to outside groups like LifeSmart, which sends in trained educators. But if classroom teachers are expected to teach the curriculum, they need to know how to create a safe environment for all young people, regardless of their personal or family background, Macklin added.

The Indiana bills from Errington and Rowray would allow school employees or contractors to teach sex ed, as long as they have “knowledge of the most recent medically accurate research on human sexuality, pregnancy, and sexually transmitted diseases.”

Before Huggins closed out her lesson, her students wanted to know if she had “the talk” in school. Huggins said she had indeed received the puberty talk in fifth grade, but not the follow-up lesson on reproduction.

Did she laugh?

“Of course,” she said.

Huggins added in an interview that shepherding a classroom of teenagers through discomfort was part of her training. Laughter, when it happens, isn’t punished.

“This is funny stuff. It’s important, it’s normal, it’s natural,” Huggins said. “And if we’re comfortable, we’ll all learn better.”

Aleksandra Appleton covers Indiana education policy and writes about K-12 schools across the state. Contact her at aappleton@chalkbeat.org.